I used to think that that sexual harassment in public was so entrenched, such a part of the fabric of our culture, that it was unchangeable.

All I could do to address it was to cope – walk fast; avoid eye contact; pretend to be on the phone; wear headphones, and if it’s daytime, blast music so I couldn’t even hear what was being said to me.

These are all completely legitimate ways of dealing with harassment, especially if you don’t feel safe responding.

But I got tired of feeling powerless and tired of believing that others who experience more serious gender-based violence in public also see no other option but to cope.

I decided to take the lead on organizing a march and rally in Washington, DC to protest street harassment.

But this is just one option for responding to public sexual assault and harassment and changing the culture that allows it to continue. Here are 7 ways you can fight it in your community.

1. Take Control – Learn How To Respond To Your Harassers

In her book “Back Off! How to Confront and Stop Sexual Harassment and Harassers”, street harassment expert Martha Langelan suggests that confronting individual harassers can buck the gender power imbalance at the heart of a harassing behavior by showing that the harassee is neither a passive object of lust nor a hysterical victim.

An assertive, forceful response can have the short-term (and very satisfying) effect of disconcerting the harasser, and the long-term effect of creating an environment that makes it more difficult for harassers to harass:

- Try all-purpose statements: “Stop harassing. I don’t like it. No one likes it. Show some respect.” Or, “When you do A, it makes me feel B, and I want C.” “When you say, ‘hey sexy’, it makes me feel uncomfortable, and I’d prefer just a hello.”

- Name the behavior and then make a command: “Your hand is on my thigh. Remove it now.” “Your comments are homophobic/transphobic. Stop it.” “You’re taking pictures of the women on this train without their consent. It’s incredibly disrespectful. Stop right now.”

Try not to get aggressive or swear at harassers. Aggressive responses can lead to the harasser becoming aggressive in turn or not listening to the anti-harassment message you’re trying to get across.

Langelan asks, “Which is more likely to make someone change their behavior calling them stupid or getting them to call themselves stupid?

Talking back to harassers can be empowering and can provide a firm and fair disincentive to harassers to continue their behavior, but harassees shouldn’t feel pressured to respond every time. That kind of undertaking could be exhausting and potentially unsafe.

Always make sure to use your instincts on whether or not a response might lead to a harasser escalating the situation.

2. Be an Active Bystander – Learn How To Intervene If You Witness Someone Else Being Harassed

One of the most poisonous effects of public sexual harassment is what it can do to the community in which it takes place.

People who often experience public sexual harassment, as well as those who have experienced public sexual assault, can become reserved and suspicious when they’re out in public.

They may avoid talking to their neighbors or miss opportunities to make genuine connections in their fear that the interaction might turn into harassment or assault. Their harassers’ attempts to intimidate and silence them can succeed.

That’s why it can be incredibly valuable for bystanders to stand up against the harassment they see taking place. Take a look at CASS’s resources on bystander intervention for an idea of the theory behind this strategy, and a few ideas for ways to intervene.

Intervention can interrupt a potentially traumatic experience for a harassee and help the harassee feel like he or she has a support system within the community, all while working toward the social justice goal of creating an environment that makes harassers less apt to harass.

If you witness harassment taking place, you can use one of the formulas above and adapt it to the situation at hand:

- Name the behavior: “You just called that woman a b**ch.”

- State a principle: “That’s not okay.”

- Make a command: “Stop harassing people.”

If you’re not willing to confront the harasser directly, you can also distract them by asking for the time or directions. Just like harassees, bystanders also have to assess how safe it would be to confront a harasser.

Some of the most difficult interventions can be the ones that need to take place among your friends. Take time to explain to your friends why harassment is wrong when they make light of harassment or assault or engage in harassing behavior.

The culture can – and will – change as more people speak up.

3. Share Your Experiences

With a problem so invisible, so under-researched, and so normalized, it’s hard to overstate the power a story has to open peoples’ eyes.

Many people, even those who experience harassment themselves, can fail to understand the emotional impact it can have.

Nothing communicates the emotional reality of public sexual harassment and assault like a story.

Last spring, my organization, Collective Action for Safe Spaces (CASS), successfully advocated for several improvements targeted to reduce public sexual harassment and assault in the DC public transit system.

We used the stories of survivors of harassment or assault on the transit system, including some who testified before the DC City Council along with us, to drive our message home.

When Liz Gorman attached her name to a powerful piece describing her assault (most submissions to CASS and the Hollabacks are by default anonymous), she said she received hundreds of emails from women who had similar experiences – as did the Washington Post columnist who later amplified Gorman’s story.

Thanks to our victim-blaming culture, many victims of harassment feel too ashamed to speak out, or as though their experience isn’t a big enough deal to share (“can’t you just take it as a compliment?”).

So, another function of blogs that post harassment experiences is to provide a support network for people who do share, through the comments and discussion of similar experiences.

If you choose to share, other victims of harassment may read about your experience and feel theirs legitimized, and hopefully share in turn. It’s awesome how one story can light fires in so many other peoples’ hearts and minds.

Find your local Hollaback branch (if you’re in DC, we’re it!). If you don’t have one, start one. Be brave and talk about what happened to you. You will find a virtual community that’s supportive of you and your experience, and an outlet for the pain and anger of sexual assault or harassment.

4. Report the Harassment

In some situations, it’s possible to report a harasser or harassing behavior. Reporting a harasser could discourage that person from harassing anyone in the future, especially if they harass you on the job and you’re able to file a report with their employer.

It can also have the valuable effect of helping authorities gather information on the amount of harassment that is taking place in a community.

Some harassing actions, like groping, indecent exposure, stalking, and assault, are illegal in most jurisdictions. That means you can, and should, report them to law enforcement.

Harassment is hugely underreported, which makes it hard for activists and policymakers to know how pervasive the problem is.

5. Organize an Anti-harassment Action in Your Community

Two weeks after I led a march in Washington, DC, a group of women marched in Kabul, Afghanistan. Women in Egypt are marching for their right to participate in civil society without being harassed or assaulted. And the culture is changing.

A demonstration can raise awareness about public sexual harassment and assault, and reclaim public space for women, GLBTQ community members, and allies. During a demonstration, haters and harassers have to participate in the space on YOUR terms for a change.

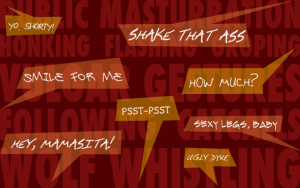

There are also projects that combine art with activism, using visual and performance art to carry anti-harassment messages. Like stories, art can instantly evoke emotion and empathy.

Artists and activists use powerful images to convey their defiance to street harassment, bust myths, or simply raise awareness. The effect can be both powerful for the viewer, and cathartic for the creators and organizers.

6. Conduct a Community Safety Audit and/or Advocate for Improvements from Your City Council

You can improve your city’s physical space and infrastructure to make it safer and more inclusive for women and GLBTQ folks by gathering data on where people are harassed, when they’re harassed, and what about the space feels unsafe.

Organize some friends and allies and take this information straight to your city council to tell them exactly what you want to see change, something CASS did in DC last year.

Your advocacy doesn’t need to be confined to physical improvements. You can call on your city’s resources to raise awareness on street harassment and make other changes that help change the culture.

In DC, we launched a campaign to get our transit system to post PSA’s warning against public sexual harassment, improve the ways that victims of harassment report incidents, and train their employees on how to recognize and address with harassment. It worked!

We’re also working to help pass a law that will make it easier for people who are harassed on the transit system to find justice, by removing a requirement that transit police officers witness the act in order to make an arrest.

7. Provide a Service to Your Community to Help Prevent Harassment and Other Gender-based Violence in Public Spaces

If you’re passionate about fighting street harassment, find an organization in your community that does work you can get behind. Consider offering them your time and skills.

Or, organize some friends to provide your own service. I recently spoke to someone who did just that. In response to a rash of attacks on GLBTQ individuals leaving a gay club in his city, he organized a group of volunteers to walk people from the club to their cars. The violence in that area stopped.

The best part about this response to harassment is all of the solutions that haven’t been dreamed up yet. If you see a need in your community, fill it! You might just create a model that will work in communities around the world.

The moment when someone is sexually harassed or assaulted in public, they often feel fear, anger, and a sense of powerlessness. And in the moments afterwards, they can be full of shame and doubt about this powerlessness.

This article is meant to give people who are harassed choices to address their feelings of powerlessness and to respond to harassment in any way that feels right.

Remember, choosing how to respond is an act of power, even if you choose to walk on and say nothing.

And no matter how you respond, it’s the harasser who should feel ashamed – not you.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Zosia Sztykowski lives in Washington, DC and has been holla-ing back to street harassment for over a year with Collective Action for Safe Spaces. CASS combines the kickass online activism of Hollaback with grassroots organizing, innovative direct services, and public advocacy to end street harassment. Follow Zosia at @zosiasztyk, and CASS at @safespacesdc.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more