Person sitting at a desk taking notes

For me, one of the scariest parts of student organizing was realizing the school or institution I had put trust into was actually working against me.

The first time I realized my beloved institution, Spelman College, was simply a cog in the system was after my participation in a sexual violence protest after the “Raped At Spelman” Twitter page was revealed.

The Raped At Spelman case was my first introduction to understanding just how much Spelman will delve into respectability politics over the care of its students. It also made me realize how Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) hide away issues of sexual violence by silencing students instead of addressing the problems.

I met alumnae at our vigil and speak out that graduated 20 to 30 years ago. All of them had stories of being threatened and suppressed by the administration from moving forward with prosecuting their sexual assault cases.

I realized my school was focused on holding on to these antiquated ideas around respectability, even if it was to the detriment of students.

It’s a scary feeling to realize the school you cherish and brag about isn’t exactly what you thought. Coming into Spelman, students are indoctrinated into the idea that we are a part of the “Talented Tenth”.

My love for Spelman is based on a learned elitism but it also stems from being in a space that is treasured — where else can you find a school where Black women can talk about hair, sex, and scholarship?

I quickly realized Spelman College — the institution — simply saw me and other students as tuition dollar amounts and only wanted to provide the bare minimum for mental health services.

I learned the hard way that this isn’t anything new. Students from across the country who regularly shut down board meetings and organized strategy for real change have been facing administrative backlash — and it’s scary.

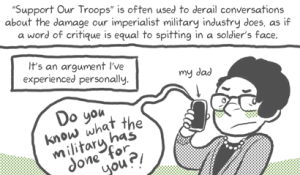

For instance, colleges and universities nationwide were in disarray when Black and Brown college students worked collectively for the #StudentBlackOut in the fall of 2015.

The #StudentBlackOut was a week of disruptions lead by student organizers across the country after the death of many Black folks by police violence.

This quickly led to administrations encouraging administrative obedience, demanding free labor from student organizers, and patronizing and diminishing the work of student organizers on the ground.

We also saw this play out when student organizers at Mizzou met with their then-President Tim Wolfe to set out demands, used strategic disruptions, eventually witness the hunger strike of graduate student, Jonathan Butler.

At the time, Wolfe avoided confrontation and repeatedly denied the issues of racism and the work of student organizers in the fall of 2015.

At Spelman, this looked like administration creating scholarships and recognizing students who were more respectable. In many cases, student organizers were brought in to help develop curriculum and procedure that we were not being paid for.

When we asked why we weren’t being compensated or if we could have meetings that were more considerate of our class schedules, we were told that this was a privilege and that our involvement wasn’t necessary.

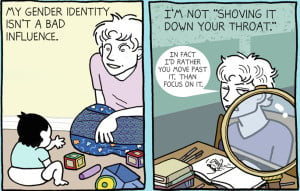

The most active naysayers and opponents of the Hillary protest — a 2015 student protest I participated in — were taught by society and by their own school administrations that social change was meant to be respectable and quiet.

The beauty and struggle of going to Spelman College — the “Black Ivy League” — is that there are many prescribed ideas about student activism.

The Spelman brand of activism means you must look a certain way, you should conduct research on marginalized people but never engage with West End community members, you shouldn’t question Spelman as an institution or call out issues that would lead to questions about “Black Excellence.”

What this all boils down to is a performance of empathy for poor Black folks but never a real analysis on how the Black elite also play a part in that oppression.

My activist cohort and I were not that.

We were loud, abrasive, and didn’t want to engage with respectability politics that would try to mold a new narrative out of our work.

Going to a historic HBCU has meant losing respect for a lot of civil rights leaders whose pockets — I now know — are lined by the funds of Democratic politicians. I have witnessed these individuals suppressing student activism if it affects their own reputation.

Not fitting the mold of an appropriate Black activist often means you may not be welcome into scholarships, leadership roles, or “liberal progressive” opportunities lead by the Atlanta Black elite that included many civil rights leaders and their proteges.

The beauty in being used as an activist token, ostracized by your school, and dealing with graduation suppression means coming to terms with the understanding that many institutions have never really protected marginalized people.

This is a theme many organizers and activists share: we crave belonging in organizing that we realize will never be found in many surface-level institutions.

I spoke with Jason Aijake, one for the lead organizers of #HUResist, a student led social justice organization at Howard University.

The many protests lead by #HUResist lead to paranoia, distress, and anxiety among student organizers who now have to reconcile the importance of the work with the risk of being expelled.

“A few days before the 150th convocation ceremony, one of my comrades was called into a meeting with an administrator and told that if we tried anything at Convocation [we] could face expulsion,” Aijake said.

Given these grim and common realities, how can student activists work through a hostile college or university administration? What does it mean to work through a system that seems bigger than you?

As always, it begins at the bottom and with small steps. In order to break down the system, we must first strategize how we want to dismantle it.

Below is a framework for student activists who want to organize sustainably and survive retaliation from school administration.

Build a Solid Student Coalition

Find a group of students that are able — and willing — to sustain the work of accountability at your school.

ATLBSU, a coalition of students from colleges and universities across Atlanta, has built and developed a network of students dedicated to holding institutions and individuals accountable. This allows for the creation of work with lasting effects.

“Coalition building is a really tricky but a very important part of organizing.The result of coalition work isn’t just one material win here or there, but typically policies, practices, and promises that are informed, intersectional, and necessary to the long term success of this movement,” said Eva Dickerson, lead organizer of ATLBSU.

Build with Faculty

This is difficult. I say this mainly because while you want to leverage folks who are willing to help, many professors have lost their jobs advocating for student activism.

Meet with new professors or folks who are open and supportive. Speak with them about how they can support the movement.

In most liberal arts colleges, allies can be found in Sociology, Political Science, Women’s Studies, and English Departments. Many Social Science departments have a lot of faculty members that can help build strategy for student organizers.

“As a professor, it’s my job to speak to students and support the work I teach. I was a student organizer and I feel the best way I can give back is to support and provide research to students looking to find strategy in a historical context,” said Rebecca Kumar, an English professor at Morehouse College.

Kumar believes this normally starts with a conversation. This is how students can reach out to professors about community building. Whether it’s going into office hours, setting up a phone call, or sticking around after class — there is always a way to reach professors.

Faculty support can show up in different ways; it may be money, insight, research, or historical theory that can be utilized for current day strategy.

Many tenured professors do not fear the administration. Try to work with as many tenured professors as possible.

Use social media to mold your narrative (and hold institutions accountable)

When issues around sexual violence were happening on campus, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat were the only ways to keep the issues at the forefront of people’s mind.

Specifically, I remember how Morehouse’s past president made terrible remarks about sexual violence — we turned photos of him into a meme. This may seem silly, but being able to critique and add humor can really draw folks into the work.

Social media is also an important tool if you have experienced discrimination from your institution because of the work you do. Being able to call out your school for its wrongdoings and critique will not only provide you with support but will inform other students of what’s going on.

In the end, Aijake did participate in the #HUResist convocation demonstration. In the wake of the event, the Assistant Director of Media Relations called Aijake’s boss and told him it was a conflict of interest for him to continue serving as news editor at The Hilltop, a student newspaper, while a part of the #HUResist movement.

“As if it’s not a conflict of interest for the administration to have control over the student newspaper,” Aijake said. “On a systematic level, painting our oppressors black changes nothing about the conditions we fight back so passionately against.”

For many student organizers, we show our love and dedication to our institutions by working day and night to hold them accountable. Yes, that work is tiring and at times we feel exploited, but we show up in whatever way we can to continue doing this work — regardless of the consequences.

No student should risk not being able to graduate or have their labor stolen by an institution.

Using social media as a platform to discuss these topics can make all the difference. And, many times, it becomes clear that folks need to engage in these topics but are nervous and don’t know how to start the conversation.

***

So what does this all mean for college students trying to change the world? It means you have to muster up courage you may never have tapped into before.

In the past, there have been times when I was terrified of being kicked out of school for speaking up. I’ve had family and friends tell me that my activism makes them uncomfortable. I have lost friends because of the work I do.

The only things that keep me going are the wins.

I do this to be able to see Spelmanites and Morehouse students who have been sexually assaulted speak up and find their voice.

Our reasoning may be different, but seeing your work result in the liberation of others is what makes social justice work possible.

I always say that I want to create and help build a better world — a world where Black and Brown folks are free and liberated from white supremacy. It ain’t easy but it’s worth it.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Clarissa Brooks is an Everyday Feminism Reporting Fellow. Clarissa is senior at Spelman College, a journalist, and a community organizer. Originally from Charlotte, NC, Clarissa works to blend her love of community, ethical journalism and scholarship in a way that will create a better world. Clarissa has been an ONA HBCU Fellow, Equality For Her Intern and Summer Fellow for Students For Education Reform.Clarissa has been engaged in community organizing work and journalism for nearly 3 years. From mobilizing communities, hosting teach-ins, leading direct actions, and developing policy her love of community always comes first.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more