Credit: Yahoo Voices

It’s September 2011, and I’m sitting on the edge of my bed.

Next to me is the guy that I just went on a really successful date with – you know, the kind of awesome where I didn’t try to sneak glances at my phone for entertainment.

After having walked me home – where, midway through, we romantically got caught in a rain storm and hid under the shelter of a tree before agreeing that the attempt was futile – he came in.

We made it up to my bedroom after he asked to take a gander.

“So, do you want to make out?” he asks.

I blurt out a surprised laugh and stare at the door. “I—uh—um,” I stammer.

Ten minutes later, and he’s taking my rain-soaked shirt off, lips plastered to my chest, and I’m trying to find a way out of this.

I didn’t want it in the first place.

Why hadn’t I outright said “no”, instead of stumbling through my surprise? How come the words won’t spill out now?

Because I’m frozen. I don’t know how. I just didn’t.

How do you say “no” politely? How do you say “no” when it’s someone that you actually really like, who you’d like to say “yes” to eventually, who flings questions at you so directly that you’re not really sure how to even start?

How do you do that?

And I don’t think that this is a unique experience that only I’ve had.

Because a lot of people – of all genders – have been in this position before.

Where we find it’s more awkward to say “no” than to lie there like a dead fish, wondering why your date isn’t picking up on the fact that you’re not kissing back.

We want our lack of enthusiasm to be enough – because, hell, it is. You don’t need to say “no” to make your non-consent clear.

We’re feminists, and we understand that only “yes” means yes. As such, this is not an article about how to prevent rape.

This is an article about how to practice saying “no” to help take away the shame and awkwardness.

It’s about effective, assertive, healthy sexual communication, whether with a date, a friend, or a long-term partner.

It’s simply about practicing, about getting in the habit of negotiating.

Because even though we’re bombarded with messages that tell us that we have bodily autonomy and should freely and openly practice non-consent, no one ever gives us the tools we need in order to do so.

And when we live in a culture where we’re not given opportunities to say no, demanding that we start practicing the foreign concept in an already-vulnerable situation is confusing at best, dangerous at worst.

So let’s teach our mouths to form the word “no” and teach our brains to stop feeling bad about it.

Five Ways to Practice Non-Consent

1. Turn down plans you don’t feel up to.

The next time that a friend asks you out to dinner, but you’d rather eat at a place different from what she suggested, let her know that you want to try something else. Or maybe suggest doing something else entirely, instead of dinner.

If you have plans with someone, but you wake up that day and it’s raining, and all you want to do is lie in bed curled up with a book instead, firmly let your friend know that you’ve changed your mind and would possibly like to reschedule.

If someone asks you to hang out, and you’re really not intrigued by the idea of spending time with them, politely, yet firmly decline.

All of these scenarios can be awkward or difficult for people, but they’re all examples of rejection that could be metaphors for sexual situations.

Start small. Practice rejecting low-risk activities to help build your way up to negotiating sex.

2. Turn down projects that you can’t take on.

The people-pleaser in all of us loooves to take on extra work, even when we know that we don’t have the time, energy, or resources to complete it.

We feel badly saying “no” because we don’t want to disappoint anyone or make them think less of us.

We want to be there for other people and their needs more than we want to be there for ourselves and take care of our own desires (and non-desires).

Again: what a metaphor!

Practice saying “no” when you know that you have to. A good way to tell if it’s the right time to turn down a project is if you feel a rollercoaster-type drop in your stomach when you’re asked.

Instead of dilly-dallying around the answer by saying you’ll think about it or reluctantly saying “yes” even though you know that you don’t want to, practice outright saying “no”.

Remember – it’s okay to put your own needs in front of someone else’s. In fact, you have every right to take care of yourself first.

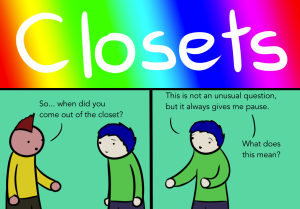

3. Talk about what consent does and does not look like with your partner.

Some people were brought up to believe that no means no (which is awesome), but haven’t quite caught on to the idea that yes (and only yes) means yes. So talk openly with your partner about what consent looks like for you.

Let them know what kinds of signs are good and which ones are bad. Talk about ways that they can ask for consent from you without fearing that they might be ruining the moment.

Discuss how you’d like non-consent (or withdrawal of consent) to be handled: do you want to talk about it? Would you rather wait until later to talk? Do you feel like a conversation doesn’t need to take place at all?

Make sure that there’s a mutual understanding between your partner and yourself that saying no to sex is just that – saying no to sex – and isn’t an indication of wavering feelings.

4. Play ‘Good Touch/Bad Touch’ with your partner or a friend.

This is a great way to talk about what you do and do not like and what kinds of activities you want to continue and which ones you want to stop.

Collect a bunch of household items (like, perhaps, a comb, a feather, an ice cube, a back scratcher, Velcro, etc.). If you’re comfortable being blindfolded, do that. And then have a partner (or even a friend, just for practice!) touch the inside of your forearm with the objects, changing up the speed and pressure.

Be honest about how those sensations make you feel. Talk about what you like; talk about what you don’t. Ask your partner to keep going if you want to, and feel comfortable asking your partner to stop if you don’t like it. Take turns!

And process the activity afterward, talking about what it was like.

5. Give a reason for saying “no”.

The truth is you don’t need to have a reason to say “no”. Your reason might just be “because I don’t want to,” and that is perfect acceptable, whether you express it or not.

But practicing giving a reason for saying “no” (as well as practicing a reason for saying “yes!”) is a good way to understand where your own feelings are coming from.

This isn’t about sugarcoating the rejection or letting people down easy. It’s about practicing being vocal about your feelings.

Try this sentence stem for starters: “I would rather not because __________. How do you feel about that?”

The more you practice, the better you might feel about what your own needs are.

And asking how they feel about it doesn’t change or challenge your right to say “no”. It just acknowledges that you saying “no” to them impacts them and you want to know what that impact is.

Practicing consent opens the door to more open and honest communication in your relationships, as well as with yourself, which is one of the most important elements of relational health.

But it takes practice.

Understand and honor that. Feel comfortable with the idea that this might be a skill that you have to learn.

And then dive in.

For yourself.

Melissa A. Fabello is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism, a feminist blogger and vlogger, as well as an online peer sex educator, based out of Philadelphia. Along with Everyday Feminism, Melissa also currently works with Miss Representation, Adios Barbie, and Laci Green’s Sex+ community. She is a second-year graduate student, working on an M.Ed. in Human Sexuality. She can be reached on Twitter @fyeahmfabello.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more