Source: The Richest

Whenever I discuss my sexuality — as someone who identifies broadly as queer and bisexual and more specifically as pansexual — I am met with a very common response: “But why do labels matter? We’re all the same.”

Often, this response comes from a place of good intentions. Many people say labels don’t matter because they believe that labels are hindering equality.

And I understand why many people think this way. It’s tempting to believe that inequality is caused by difference. It’s tempting to think that the only way to ensure that people don’t treat others differently is by ignoring our differences.

We’re often socialized to view differences as the cause of inequality, rather than to understand oppression and inequality as systemic.

Acknowledging our privilege can make us feel really uncomfortable and guilty because it requires recognizing how we’re complicit in oppression.

For this reason, it’s way easier to use labels as a scapegoat – to pretend labels are the root of inequality – than to do the difficult work that is acknowledging our privilege.

But here’s the thing: Labels don’t cause inequality. People do.

Don’t get me wrong: Labels can certainly be used as tools of oppression. Labels can be both useful and harmful — it depends on where and how we use those labels.

Let’s look critically at some of the ways in which labels can be harmful and beneficial.

How Labels Can Be Harmful

When it comes to sexual and romantic orientation, labels are descriptive and not prescriptive. They should describe our identity — not prescribe who we’re attracted to.

This is to say that labels should not dictate our identities to us. Rather, we dictate the label. For example, if someone identifies as lesbian, but finds a man sexually attractive, that’s perfectly fine.

Labels can be incredibly oppressive when we impose labels on others. Often, imposing labels on people is rooted in a lot of queerphobia and monosexism.

For example, if someone uses the word “gay” to describe a man who doesn’t identify as gay, but exhibits behavior that is stereotypically associated with gay men, this can be pretty oppressive. That’s telling someone what their sexual identity is, and this is not okay.

Secondly, you’re perpetuating stereotypes about gay people — and those stereotypes are dangerous as they often cultivate homophobia.

Let’s look at another example. Non-monosexual people — people who are attracted to more than one gender — are often defined by the gender of their partner.

For example, I’m currently in a relationship with a man. Often, we are referred to as a “heterosexual couple,” and I’ve been told by many gay people that I’m not queer because I’m dating a man.

The label of “straight” is imposed on me, despite the fact that I don’t identify as heterosexual.

This is a direct example of monosexism and bi/pan-erasure, as it perpetuates the myth that people can’t be attracted to more than one gender.

Imposing labels on others can also limit gender expression.

Society often conflates sexual orientation with how we express and perform gender.

For example, we often assume men with qualities Western society recognizes as feminine to be gay and women perceived as “masculine” to be lesbian.

Similarly, people who seem to conform to gender norms are assumed to be heterosexual.

Because of this, many people fear being labeled an orientation they are not because of how others may or may not perceive their gender.

As a result, we limit and conform our gender expression to stereotypical norms. This is particularly harmful for non-binary and gender non-conforming folks.

Often, people who are not heterosexual are also pressured into choosing a label that describes their sexuality.

Non-monosexual people and people who don’t label their sexuality are dismissed as being “confused.”

While being attracted to more than one gender definitely does not mean you’re confused, being confused about your sexuality is not a bad thing at all.

It’s okay to take time to figure things out, and it’s certainly okay to want to avoid labeling your own sexuality.

The best solution to this problem? Let people decide what to call their own sexuality, if they choose a label at all. It’s of the utmost importance that we respect how people describe their sexual orientation.

How Labels Can Be Useful and Empowering

Discussing Oppression

Labels can be incredibly useful in discussions about privilege and power.

When I discuss my sexuality and my lived experiences as a pansexual person, I’m often told that my sexuality doesn’t matter, that we’re all the same. But the thing is, we’re not all the same.

My life is different from a heterosexual person because I encounter queerphobia. My life is different to that of a gay person, also, because I am oppressed by monosexism.

Unlike a heterosexual person, I’m likely to face discrimination in the workplace, in university, and in my community because of my sexual orientation.

I can’t assume that I can speak about my partner(s) or love interests with anyone I meet because, unlike heterosexuality, my sexuality is not the assumed and accepted norm.

Being bisexual means that I’m more likely than monosexual people – including homosexual people – to experience gender-based violence, experience homelessness, be closeted at work, and feel suicidal.

When I plucked up the courage to tell people I’m bisexual, many people – including my therapist – assumed I was lying and was actually gay.

What’s more is that organizations that cater specifically to the needs of non-monosexual people receive less funding than those that cater to homosexual people.

My sexuality shouldn’t determine whether I have access to healthcare, how likely I am to suffer from domestic and sexual violence, whether my sexuality is erased in the media, or whether I’m likely to live in poverty. But it does.

And we need to discuss why society is like this.

Without “labels,” we don’t have the vocabulary to discuss oppression.

Requesting that people don’t use labels to describe sexuality may come from a good place, but ultimately, it silences oppressed people and makes it difficult to discuss our own oppression.

Think about it: As a queer person, I want to be able to discuss how it feels when people discriminate against me.

I want to speak about how it hurts when people around me make heterosexist comments. I want to challenge the ways in which bisexual women are simultaneously sexualized and erased by society.

But if I don’t have the vocabulary to discuss those things, I have to keep it all bottled up, and that’s not productive or healthy.

Inequality exists because of power structures. Labels enable us to discuss these power structures – they don’t cause inequality themselves.

When you suggest that I’ll be treated fairly if I don’t label myself as pansexual, you’re implying that my pansexuality is the problem.

But I’m not oppressed because of my sexuality itself — I’m oppressed because of society’s dismissive and intolerant attitude towards my sexuality.

Finding a Community and Experiencing Solidarity

Using labels to describe our sexuality can also help us find solidarity in a heterosexist world.

As I’ve explained, our sexual orientation often affects the way society treats us. Most spaces, literature, and media cater to heterosexuality. Queer narratives are often erased and ignored by the mainstream.

As a result, many of us feel alone, “weird,” and unaccepted.

This can contribute to low self-esteem, mental illness, and suicide.

Feeling unaccepted by the media also means many of us are tentative to come out and discuss their experiences.

I think that’s one of the scariest things about heterosexism: It isolates you. It makes you feel hopeless and unsupported.

Because of this, it’s helpful to find a supportive community that understands and centers queer experiences.

As a queer person, I’m afraid to speak about my experiences of discrimination, love, and sex in most spaces because a majority of spaces are antagonistic towards queer people.

Finding a space that’s specifically queer-friendly is liberating because there, I can speak about my experiences and still be loved, understood, and accepted.

Creating queer-friendly spaces and communities is revolutionary. It helps us support one another, share advice and feel loved in a world that constantly tries to dehumanize us.

Labels enable us to create these spaces.

Labels as Expressions of Personal Identities

Growing up, I didn’t have any “labels.”

I had no community. I had never heard the word “pansexual” — or even “bisexual.” Thanks to early exposure to The Oprah Show, I knew that homosexuality existed, but I had never heard of people who were attracted to more than one gender.

Sexuality was always represented as a binary to me: As a pre-teen, I thought one was either homosexual or heterosexual.

So imagine my confusion when I realized I was attracted to both girls and boys. I had no idea what to call myself or whether it was okay to feel those feelings or not.

I felt confused, hurt, and completely alone.

Eventually, I learned about bisexuality. I realized that people could be attracted to more than one gender.

After realizing I was literally attracted to people of all gender identities and expressions equally, I decided that pansexuality described my sexuality best.

Finding these “labels” was a relief for me. Learning about bisexuality and pansexuality made me feel like I was not alone. It made me feel validated.

The journey to self-acceptance was a tumultuous one, and it shaped much of who I am today. My sexual identity – or the “label” I use – is incredibly important as it represents this journey.

In this light, when people – particularly homosexual or heterosexual people – say my sexuality “doesn’t matter,” it feels a lot like erasure. My sexual and romantic orientation is a huge part of who I am, and I absolutely love my “labels.”

When I say that I’m queer, pansexual, and bisexual, I’m saying:

“Here. This is the battle scar that lies across my heart. Society has tried to erase my existence. It’s tried to make me invisible. It’s told me that people like me don’t exist. But I’m still here. This is my community, identity, and journey. This is who I love and how I love. I am resilient, I am bursting with love, and I am beautiful.”

While some people don’t feel that their sexuality is an important part of who they are, many of us do — and when you say our sexuality doesn’t matter, you’re erasing a big part of us.

***

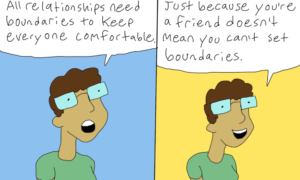

Labels can be tools of oppression as well as tools of resistance. It depends on how and when we use them.

It’s incredibly important to be mindful of the way we use labels. Labels can be helpful and empowering if and when we apply them to ourselves, and harmful when other people impose labels on us or define us by our label.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Sian Ferguson is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism. She is a South African feminist currently studying towards a Bachelors of Social Science degree majoring in English Language and Literature and Gender Studies at the University of Cape Town. She has been featured as a guest writer on websites such as Women24 and Foxy Box, while also writing for her personal blog. In her spare time, she tweets excessively @sianfergs, reads about current affairs, and spends time with her gorgeous group of friends. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more