Source: Precept

Trigger Warning: This article deals with the topics of consent, sexual assault, and sexual coercion.

Author’s Note: The terms “woman” and “man” are used throughout this article.

These culturally defined terms drive and perpetuate myths around sex. Though the emphasis of this article is around men and women in heterosexual relationships, the impact of these stereotypes is not isolated within those identities.

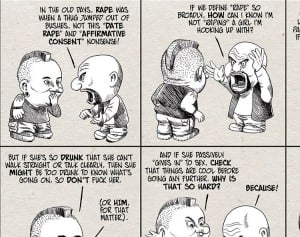

Everyday Feminism has written about rape (trigger warning) and sexual coercion, as well as the ways in which social norms and gendered stereotypes contribute to rape culture.

That is not what this article is about.

This article is about the ways in which social norms and gendered stereotypes lead individuals, particularly women, to negotiate their own sexual desires with the expectations around sex.

And sometimes these negotiations around when to have sex and when not to can lead women to have sex when they don’t really feel like it.

I am a young, heterosexual feminist woman. I have read all of the articles about healthy sexual expression, safe sex, and consent. I could go on an hour-long rant on the role of culture and social norms in limiting our sexual expression.

And yet I struggle with every new sexual partner to remember to assert my voice, to tell my partner what I want and don’t want, and sometimes I struggle to say “no,” “stop,” or “wait.” I’ve gone along with sex when I didn’t really want it — just to please my partner or to feel desirable.

It’s not an easy thing to admit. There are feelings of shame, guilt, and irresponsibility. It is not the image of the sexually empowered woman that I strive to promote. But it’s my reality, and it’s the reality for many other people.

Healthy relationships are based on honest communication and respect.

Understanding the ways in which culture influences our choices around sex can empower partners to talk about their desires and needs openly and sincerely.

The following gendered myths can cause breakdowns in communication regarding sexual desire in heterosexual (and queer) relationships, depending on how much the partners ascribe to gendered stereotypes and expectations.

Myth 1. Men Are Always Ready for Sex (And Women Need to Be Convinced)

The stereotype that men always want sex and that women have a low sex drive are toxic (and untrue) messages that can influence how we communicate our desires.

There are many ways to understand the terms “sexual desire” and “sex drive.” In this article, I am defining sex drive as the need for physical sexual release.

Desire, on the other hand, is the psychological, emotional, and physical want for sexual contact. Both are affected by our preferences, environment, culture, and biology.

The truth is that an individual’s sex drive is influenced by a variety of things. Natural hormone levels, stress, aging, medical conditions, medication, environment, and mental health can all contribute to someone’s sex drive.

Additionally, aspects of the relationship or partnership can contribute to sex drive: trust, communication, and attraction are all factors. Finally, personal attributes like self-esteem and beliefs or values around sex also influence sexual desire.

Regardless of sex or gender expression, our sex drive is influenced by more than just our testosterone.

Our drive for sex fluctuates and varies by person. Gendered expectations limit our ability to communicate these personal differences. The emphasis on sex also further marginalizes individuals who identify as asexual.

The idea that men always want sex may lead those who identify as more masculine to pursue or have sex when they don’t really desire it. The stereotype of the “hypersexual man” is an archetype of masculinity that individuals may feel pressure to live up to.

Additionally, the negative stereotype of the low sex-driven woman may make individuals feel like they cannot be honest about not wanting or desiring sex.

The fear of having their sex drive under scrutiny or generalized may lead those who identify as more feminine to have sex when they are not “in the mood.”

Being more sensitive and aware of the factors that contribute to sex drive can help foster better sexual communication.

Decisions around whether or not to have sex should be about desire, not about stereotypes and social expectations.

Myth 2. Women’s Worth Comes from Their Sexual Attractiveness

Pressure to have sex can also come from society, the media’s emphasis on physical attractiveness, and the sexualization of women.

The way that women are portrayed in television, movies, magazines, and music overemphasizes their physical appearance and sexual desirability over other characteristics. This disproportionate emphasis on sex creates the gendered association between femininity and sexuality.

If femininity is associated with sexual desirability, then women may feel like if they don’t have sex, they are not desirable in other ways.

The other factors that make up their identity don’t seem as valuable as their sexuality. Therefore, women may choose to have sex in order to meet standards of worth imposed by society.

These expectations don’t necessarily reflect their own desires or the desire of their partner. Instead, both individuals may strive to fulfill the idealized sexuality of Hollywood.

Healthy sexual partnerships are not built around trying to live up to abstract messages around desire, attractiveness, and sexuality.

Instead, healthy sexual partnerships are fostered when all people involved feel able to express their desires without the fear of their personal value diminishing.

Our sexual desire and desirability is different, shifts, and changes, and we should feel comfortable knowing and communicating that about ourselves.

Myth 3. It’s Not Sexy for Women to Discuss Desire, Pleasure, and Needs

In order for individuals to feel comfortable saying “no” when they don’t feel like having sex, people need to feel comfortable actually talking about sex.

Many things interfere with individuals feeling comfortable talking about their sexual desires and needs with their partners, and social stereotypes around femininity often stigmatize the discussion surrounding sex and pleasure.

If women feel like they can’t talk about sex without evoking stereotypes around their femininity, then they may not feel comfortable discussing why they don’t want to have sex.

The idea of active and enthusiastic consent is an important component in helping to shift this myth. Being able to talk about what makes us feel sexy and the variety of things that impact our sex drive can help increase pleasure and satisfaction in sexual partnerships.

Myth 4. Women Should Be Caretakers in Relationships

There is still a lingering association between femininity and emotional caretaking in relationships. The idea that women should put other people’s needs and wants before their own can interfere with the prioritization of their own desires.

Just like initiating sex can be emotionally vulnerable, declining sex can feel vulnerable as well. The fear of hurting or offending your partner can override your own desires.

This, compounded with the expectation to take care of and please others, can hinder the ability to say “no.”

Negotiations around sex and pleasure are a part of relationships. We make compromises, try new things, and make choices in order to please both ourselves and our partners. This is a normal and healthy part of partnerships.

These choices, however, shouldn’t be rooted in archaic and patriarchal stereotypes of “women” and “men.” Rather, they should come from a place of respect for the needs and desires of everyone involved.

Being sensitive, honest, and respectful towards your partner(s) should not be reduced to gendered stereotypes. It’s everyone’s role to listen and to be receptive and supportive to their partners.

Myth 5. Men Want to Have Sex, Even When Their Partners Don’t

The stereotype of the “hypersexual man” not only implies that men always want sex, but it also implies that men want to have sex even when their partner does not want to.

This is a damaging stereotype for relationships and paints a narrow picture of masculinity. Most men want to have positive and healthy relationships. They want to make their partners feel good and have sex be a mutually enjoyable experience.

Dare I say, men want their partners to want the sex that they’re having.

Of course it can feel uncomfortable to have someone say “no.” A thousand things may cross your mind about your own sexual desirability, your relationship, your performance, and your own sex drive.

These fears exist for all individuals in all sexual relationships, and can inhibit someone from saying “no.”

Sex is best when it involves all parties wanting and desiring sex. And men know this.

***

Our cultural messages about sex aren’t just gendered. Expectations and stereotypes related to race, sexuality, ability, and other identities can intensify and stigmatize desire and influence our choices about sex.

So what do we do?

- Work to understand how your sexual desires are impacted by factors outside of your sexual relationships.

- Tease apart your own sexual desires and the cultural and social messages you have received about your sexual desires. Where have you gotten your messages about sexuality?

- Explore your sexual desires with curiosity. What impacts when you want to have sex? In what situations do you find that your desire spikes, and in what situations do you see it diminish?

- Work to communicate with your partners about sex, both when you want it and when you do not want it. Be honest with both yourself and others about your needs, wants, and desires.

As I said before, our choices about sex are rarely simple. They’re influenced by a variety of different factors.

It can be hard to navigate your desires with your partners’ desires in the midst of a society that is bombarding you with messages about sexuality. But your sex life should not be defined by stereotypes.

You have the final word, and “no” should always feel like an option.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Aliya Khan is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and identifies as a feminist, activist, and life-long learner. She provided crisis support to survivors of abuse at the Women’s Center and Shelter of Greater Pittsburgh and is currently living, studying, and writing in the Pacific Northwest.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more