When a behavior feels like second nature to us, it’s hard to imagine that it could have been learned.

That’s why so many people intuitively feel that gender roles must be biological – and it seems like every day, there’s a new study to support that claim. But how conclusive is the evidence, really?

It turns out a lot of tendencies that seem almost reflexive are actually learned. But because they’re so deeply engrained in us from the time we’re born, they affect the way our brains develop, and it feels as if we were born that way.

I’ll go through some of these myths about gender one by one, but here’s a problem that applies to all of them: Claims about evolutionary gender differences, especially those citing the animal kingdom, equate males with men and females with women, when in reality men can be biologically female and women can be biologically male.

While I will debunk some of these theories by citing research specific to male and female animals and bodies, it’s important to keep in mind that this research doesn’t translate directly to men and women. In fact, the difference between sex and gender further challenges any claim that men and women behave as they do because of X and Y chromosomes.

Here are a few gender stereotypes that are not as biologically rooted as many think.

1. Men Are Better at Math and Science

In 2005, former Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers came under fire for suggesting that women were underrepresented in scientific fields due to “issues of intrinsic aptitude.”

While Summers ended up apologizing, many thought he didn’t have to. After all, isn’t it the duty of universities to consider all possible theories rather than let politics influence their search for objective truth?

Generally, yes – but if you’re going to make a statement so potentially harmful, your evidence had better be rock solid. And in this case, it’s not.

Claims like Summers’ contribute far more to the gap in STEM fields than differences in “intrinsic aptitude.”

Lately, more and more research is proving that socialization has a stronger influence on the STEM gap than we ever imagined. Differences in many measures of mathematical and scientific abilities evaporate when socialization is accounted for.

In one fascinating study, the performance gap on a mental rotation task – which shows people an object and asks them which of several pictures depicts the same object in a different position – disappeared when participants were instructed to picture themselves as stereotypical men beforehand.

Another phenomenon suggesting that self-stereotyping contributes to gender and racial gaps in STEM is stereotype threat: When women and people of color are reminded of their identities before taking math tests, their scores drop significantly due to the discouragement of knowing they’re not expected to do well and the pressure to prove that stereotype wrong.

Perhaps partially due to stereotype threat, the gender gap in math performance correlates negatively with the gender equality present in a culture. In countries where the least sexism exists, the gap disappears. In addition, the daughters of mothers who believe in gender stereotypes about math ability perceive themselves to be less good at math.

These studies all highlight the power of parents, teachers, and other authority figures to close the STEM gender gap by teaching children that boys are not, in fact, better at math and science.

2. Women Are More Emotional

The evidence is all over the place with this one, but it does unequivocally show that men are more likely to hide their emotions, so the differences in behavior we may observe probably have more to do with socialization than heredity.

A study from earlier this year, in which women reported stronger reactions and showed greater activation in motor regions of the brain speculated to correlate with emotional expression in response to emotional images, was presented by the media as a boon for gender stereotypes. But self-reports aren’t always the best indication of true feelings, and the fact that a trait appears on a brain scanner doesn’t make it innate.

Another study with different results showed men and women “blissful, funny, exciting, and heart-warming” videos and measured their skin conductance, a response of the sweat glands that correlates with emotional reactions to stimuli. Men demonstrated a greater physiological response to all four types of videos, especially the “heartwarming” ones. Yet, afterward, when asked to rate how the videos made them feel, women reported stronger reactions.

In a survey of over 2,000 men, 67% said they were more emotional than they appeared. Surprisingly, 40% of men ages 18-24 said they had cried in the last week.

Suppressing emotions can harm your health, strain your relationships, and even make you less likable. And the stereotype that women are more emotional isn’t particularly helpful either.

John McCain’s use of the term “emotional” to discredit Hillary Clinton is one of many instances when the perception that women are more emotional made people take them less seriously.

“Emotional” shouldn’t be an insult in the first place, but since it often is, we should be skeptical of a society that attributes this quality to women and make room for people of all gender identities to express emotions.

3. Men Have Higher Sex Drives

It only takes a quick glance at the sex subreddit, replete with questions from men with women partners who have higher sex drives than them, to realize this isn’t always the case.

“It is not uncommon for women to desire sex more often than their male partners,” Dr. Abraham Morgentaler, author of The Truth About Men and Sex, told Glamour in a recent interview. But is the stereotype true on average?

Western culture imposes disproportionate shame on women for expressing sexual desires. This is known as the sexual double-standard, and research has shown that Americans promote this standard by viewing men positively and women negatively for having many sexual partners.

It’s likely that this social norm is contributing at least in part to the finding that men often profess a greater interest in sex.

For example, while one study found that more men were interested in casual sex when no context was given, it also found that women were equally interested in a hypothetical scenario in which they would not be judged and their partner would be a “great lover.”

In addition, a study by the dating service Elite Singles found that women and men were on the same page regarding frequency of sex: 65% of women and 69% of men said a few days a week was ideal. A survey by fertility app Kindara similarly found that about three-quarters of women wanted to engage in sexual activity over three times a week, and over half wanted to have more sex than they were having.

The book What Do Women Want? Adventures in the Science of Female Desire debunked pretty much every stereotype under the sun regarding women’s sexuality a couple years ago.

In it, author Daniel Bergner used scientific research and evidence from the animal kingdom to argue that women want sex as much as men, and that these desires are “not, for the most part, sparked or sustained by emotional intimacy and safety,” as stereotype would have it.

Another stereotype Bergner’s research discredited was that men are naturally the initiators of sex. At least that’s not how our closest animal relatives do things: Bergner told Salon he was struck by how female Rhesus monkeys were “relentlessly stalking” and “chasing” the males.

He also cited a study showing that blood flow to the vagina increases when people view a wide range of sexual images – even more types of images than penises reacted to, debunking the myth that women (conflated in the research with people who have vaginas) are less visual.

As to the reason for the wider range, he offered several explanations including: “We’ve very strongly eroticized women’s bodies and, of course, women are going to feel that as well as men.”

But sex drive is something so primal, you may think – can it really be learned? Well, cultural differences in sexuality suggest it can be learned to a great extent.

When studying two central African cultures, anthropologists Barry and Bonnie Hewlett were surprised to find that the men were not aware of masturbation. When another anthropologist, Robert Bailey, tried to obtain semen samples from men in the Ituri forest of the Congo, they also didn’t understand what masturbation was, and even after it was explained to them, many returned samples mixed with vaginal secretions.

Even in Western cultures, the belief that men are more sexual has not always held. In the Middle Ages, it was common knowledge that women had higher sex drives.

Saint Isidore of Seville called women “very passionate… more libidinous then men,” and St. Jerome similarly wrote, “women’s love in general is accused of ever being insatiable; put it out, it bursts into flame; give it plenty, it is again in need.” (Yes, sex was a topic that the saints addressed.)

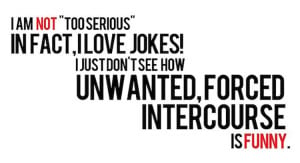

In addition to simply not being true, the conventional wisdom that men are always interested in sex is dangerous because it implies that men cannot be sexually assaulted when they absolutely can.

Further, the belief that women are not very interested in sex and need to be talked into it is used both to justify pressuring women into sex and to sex-shame women who seek it out, when in reality, it’s totally normal to want and seek out sex regardless of gender.

***

I question these gender roles not to criticize those who happen to relate to them but to validate those who don’t – because although claims about the innateness of gender usually aim to be descriptive, they become prescriptive very quickly.

People who call gender stereotypes natural aren’t necessarily trying to encourage them, but they often end up stigmatizing less “natural” behaviors and pressuring people to act according to their gender’s supposed nature.

Even when differences between groups exist, it’s important to recognize that they don’t apply to everyone and often don’t even apply to most people. Ultimately, the only way to know about someone’s intellectual proclivities, emotions, or sexual desires is to ask them.

Besides, getting to know someone is more respectful – and more interesting – than making assumptions.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Suzannah Weiss is a New York-based writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Salon, Seventeen, Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post, Bustle, and more. She holds degrees in Gender and Sexuality Studies, Modern Culture and Media, and Cognitive Neuroscience from Brown University. You can follow her on Twitter @suzannahweiss.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more