Source: Odiami

(Content Warning: Rape and Rape Culture)

Imagine this – you’re sitting at home, catching up on Arrested Development or whatever show you’re into now, and your friend calls.

This friend tells you about their recent sexual assault.

Your heart stops. You don’t know what to do, what to say, or how to respond.

You’re feeling an incredible mix of things – anger towards the perpetrator, fear for your own safety and for everyone else, sadness that your friend was violently robbed of so many things, pride that this friend trusted you.

Or maybe you feel nothing at all.

There is no right way to feel when a friend tells you about a sexual assault.

It is an incredibly complex time for both of you – and a critical time. The way you respond can have a huge impact on your friend and the relationship that you two will have as you move forward.

Below are some tips to handle the situation with sensitivity and grace. But before we can delve into practical tips, we have a few things to consider:

1. Anyone who identifies anywhere along the gender spectrum can be the victim of sexual assault.

We have a societal notion that only women can be assaulted but the truth looks much different. Women, men, trans* people, and people of all genders can be violated.

For this reason, I have used “they” and “their” to describe the survivor in hopes of being inclusive of all expressions of gender.

So if your friend isn’t a woman and tells you they were raped, don’t dismiss it simply because they’re not female.

2. Anyone who identifies anywhere along the gender or sexual orientation spectrum can commit rape.

Our image of a rapist is usually of straight men raping women. While this is most common, it doesn’t mean that people of other genders, including women, and people of other sexual orientations, like LGB, can’t or don’t sexually assault people.

So if your friend says someone other than a straight man raped them, don’t dismiss it either.

3. Understanding what sexual assault means for the survivor will help you be as sensitive as you can be.

Sexual assault is a violent act that cuts people to the core. It strips away a person’s sense of dignity, autonomy, and control. It is violence against a person’s most inner and personal self. It is devastating, in every possible way.

Before you help a friend, you must try to truly understand how awful the experience must have been for them. That intention is possibly the most healing intervention that anyone can provide.

4. There are structural and societal barriers that exist to keep survivors of sexual violence from seeking help and care.

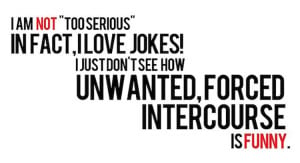

The term rape culture perfectly embodies these barriers. Many rape survivors are not believed, are blamed, and are further shamed for this violent crime that was committed against them.

Unfortunately, these are real barriers that your friend will face in speaking about their experience, including to people who are there to help them.

The judge who wouldn’t allow the word “rape” to be used in a rape trial, the media’s coverage of sexual violence under “odd news” – these are but two examples of the larger structural barriers to accessing care after a sexual assault.

How can a survivor feel safe seeking help from institutions that very publically diminish the seriousness of sexual violence?

So if they’re not ready to speak to someone like the police or a therapist, don’t push them. While it’s coming from a well-intentioned place, pushing them only further makes them feel like they’ve been forced to do something they don’t want to do.

And that’s probably the last thing they need after being raped.

What To Do Immediately After a Sexual Assault

If your friend told you within seven days after the sexual assault, there are a few practical things to consider related to collecting evidence in the case your friend wants to filing a report with the police.

Now, your friend may want to, may be unsure, or may not be interested in pressing charges. That’s completely their choice to make.

Remember, evidence can only be collected at that time but the decision to press charges can come later.

So if your friend is interested or is unsure, it is a good idea to go to a local emergency room because it leaves them that option later for them. Here are some things to know:

- The emergency room staff can perform a forensic medical exam – often called a rape kit – and will collect evidence against the perpetrator. This can happen up to seven days after the time of the assault.

- In order to gather the most evidence, it is recommended that the survivor not shower, use the restroom, eat, brush teeth, or change clothes after the assault.

- The survivor also has the option of providing any other evidence that may support their case, such as sheets, blankets, or anything that may have DNA from the perpetrator.

- The hospital will keep the evidence so bring a change of clothes for your friend if necessary.

- In the case of genital rape, a doctor may test for STI’s or recommend future testing.

- The doctor may also prescribe emergency contraception if there is a risk of pregnancy.

- Most hospitals provide an advocate for sexual assault survivors to provide support during this process. You may request this person’s presence from the local rape crisis center if one is not sent automatically. In addition to emotional support, this advocate will provide information regarding the survivor’s legal rights and options. These advocates are also trained to support friends and family members so you may also feel free to discuss your concerns with this person.

How To Support Your Friend

Regardless of when the assault took place, these tips will be useful in supporting your friend:

1. Listen

Of course, listening is the first on the list. We’ve all heard it before.

But wait – I’m going to call on you to listen in a different way.

Usually when we sit down to listen to a friend, we have an agenda. We are looking to hear something in particular, or we’re looking out for ourselves by seeking to say the perfect thing.

We usually want so desperately to “get it right” that instead of staying present and really, truly hearing our friend’s words, we’re planning what to say next.

But our minds can’t simultaneously hear, process, and plan. We need to listen fully and stay completely present in the moment, without planning our next move or fixating on what we want to hear.

Your friend deserves to be truly heard – we all do, but there is an extra layer of need after surviving a violent crime.

There is nothing wrong with silence. When your friend is finished speaking, take a moment to gather your thoughts before saying anything.

That will ensure that you have a moment to process what you heard, and allows you to avoid planning ahead for your next words.

2. Remind Them That It’s Not Their Fault

Here are some examples of what you should NEVER say to a survivor:

- What were you wearing?

- What did you do to lead them on?

- Were you drunk?

- Were you flirting with him? Did you give him the wrong impression?

- Why didn’t you fight back?

- Are you lying?

Avoid any variation of those phrases that puts the blame on them and remind them it is NEVER their fault.

There was nothing they could do to deserve or ask to be raped. The responsibility always completely lies on the rapist and not them.

Just like if someone is robbed, the robber is the only one responsible. Even if the person robbed was wearing fancy clothing, walking alone at night, holding a purse with money in it – i.e. just going about their business – it’s not their responsibility to not get robbed.

At most, they can try to reduce their risk of being robbed. But it’s always the responsibility of the perpetrator to not commit the crime.

3. Ask Questions in a Sensitive Way

It’s essential to ask questions without judgment. Of course, you may want to ask questions so that you can get a better sense of what happened, but be honest about that.

“I’m going to ask you these questions because I want to really understand your experience, not because I think you did anything wrong, is that okay?” is a great way to communicate your intention before asking a question.

It’s generally a good idea to avoid asking questions that start with, “why”, because it seems so loaded with judgment. There is always a better way to reframe the question.

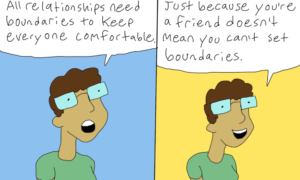

4. Honor Your Friend’s Autonomy

It is so very important to honor your friend’s autonomy and ability to make decisions about their life. That’s why I argue that despite your best intentions, it is never appropriate to tell a friend that they need or have to get therapy, to tell the police, to tell their parents, etc.

At the time of the assault, your friend was violently stripped of their ability to make decisions, to be a full and complete human with control of their life.

It isn’t your intent, but when you say that they “need” to do something, you are taking away their power, just as their perpetrator did.

If you feel strongly that your friend could benefit from talking to a trained listener (and you’re probably right), there are really great ways to have that conversation that avoid saying what they “need” to do.

Asking with genuine curiosity if they have ever considered talking to a therapist is a great place to start, but make sure you are open to whatever answer they give you.

5. Understand that How a Survivor Responds is Complex and Varied

Everyone experiences sexual assault in different, complex ways. Your friend’s response will be multi-layered and their recovery will not be linear.

Your friend may seem fine in June and then be completely devastated in August. They may feel completely numb one day and angry the next.

This is okay. And it’s super important that both you and your friend understand this and that any reaction is a perfectly normal reaction.

It is essential to understand the complexities of this experience. This relates to numbers one and two of this list, but extends beyond those.

Listen to why your friend may be devastated by this experience, even beyond the typical, healthy, and appropriate responses to a horrendous crime.

- Is your friend a strict Catholic who may have been waiting until marriage for their first sexual activity?

- Is your friend a trans* woman who may now be outed?

- Is your friend a man who is feeling shamed by stigma about men and sexual assault?

Understanding the political and cultural implications of sexual assault and what they mean for your friend will be useful in understanding the complexity of their experience.

If you don’t understand, do some research. Tell your friend that you are still learning, and that you’re curious. Then listen.

6. Help to Establish Safety

You will have helped to establish emotional safety by listening to your friend and by not saying the wrong thing to them, but there is another critical component of safety, as we all know.

Physical safety will become a major factor in the way that your friend is able to re-navigate their life. Are they afraid to walk to class or work alone? Can they feel safe getting in and out of the car, on the bus, in a crowd, or alone?

One of the most crucial parts of establishing safety is finding ways to continue about life. If fear of everyday tasks becomes overwhelming for your friend, there may be ways for you to help.

Offer to accompany your friend on whatever errand or task seems daunting or scary. When you walk your friend home, turn on the lights in their apartment before they walk in.

Your friend may need help feeling safe in their life, and there are a million small ways that you can do that, depending on your friend and the relationship that you two have.

7. Offer Resources

But only if your friend wants them! Here’s the best way to find out if your friend is interested – Ask!

If they aren’t interested, don’t offer resources.

If your friend is interested, here are a few to get started:

- Rape Abuse & Incest National Network

- National Sexual Violence Resource Center

- Tips for finding a therapist

8. Take Care of Yourself

Self care is an essential part of helping others. You can’t show up fully to your friend, as much as you’d like to, if you haven’t shown up fully to yourself.

Of course, taking care of yourself will mean different things to different people.

For you, this may mean learning how to be around the perpetrator if they are known to you. (Tip: Ask your friend how they want you to respond!)

This could mean learning how to feel safe in your own life. Or it could mean exploring how to hear how awful the world can be while still appreciating the beauty of this life.

Whatever self-care means to you, it’s important you figure out how to do it.

Caring for a loved one who has survived a trauma of any kind can be exhausting. You’re dealing with really real, scary, and raw emotions.

In order to truly help your friend, you need to be emotionally healthy. You can’t help a friend if you are struggling more that they are.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Sarah Ogden Trotta is a psychotherapist at ContactLifeline, Delaware’s Rape Crisis Center. She can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @xsogden. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more