Credit: MTCC

Here is something that we all know – humans are social beings. We thrive in community and rely on each other for our very survival. We are inclined to participate in each other’s lives for our own health and happiness.

In order to do this, we must be able to identify with others through our capacity for empathy.

Empathy is often described as the ability to recognize and identify with feelings that we see in another person, whether real or fictional. We have actual neurons in our brains (mirror neurons) that help us empathize with a person in front of us.

If we see someone fall, we feel embarrassment and pain. If we see someone experience joy, we feel happiness.

This is simple biology – our brains are wired for interpersonal connection and community.

But somewhere along the way, our understanding of community has shifted, and our capacity for empathy has been lost for many people.

We’re not saying that people don’t care about anyone. But we are emotionally connected to far fewer people than past generations and this has a negative impact on our civic engagement in our communities.

We see it all the time when we:

- Walk by people without saying hello

- “Like” an important moment of a friend on Facebook instead of calling to share our congratulatory wishes

- Stay at home on Friday nights to watch our Twitter feeds instead of socializing with the people who we love.

In many ways, we are more connected than ever with the internet, cellphones, etc. But most of us actually still feel very, very alone.

Empathy is an instinctive capacity to care for another person. But we train it out of our bodies by shielding our eyes to what we do not want to see.

Instead, we stop viewing each other as living creatures, but rather view human connection as a non-stop source of superficial entertainment.

These small choices that we make – to check our email instead of saying hello, to RT a joke instead of telling it to a partner – have consequences for ourselves and our communities.

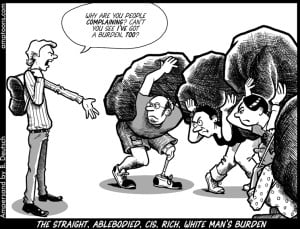

Courtney Martin recently wrote a piece begging us to notice the tiny acts of violence from which people die every single day – the children who go without food, the seniors who can’t pay their heating bill, the micro-aggressions that keep people from accessing the services that they need and to which they are entitled.

These are all forms of violence that can be traced back to a lack of empathy for the members of our own community.

We shield ourselves from this violence because it is hard, and uncomfortable, and inconvenient to consider the roles that we play in allowing these forms of violence to take place.

The tragedy in Newtown struck a chord with us because it is simultaneously imaginable and unimaginable. We can imagine a lone gunman holding up a school because that is our collective fantasy of how violence appears: there is one, clear bad guy, and he goes after the most innocent of us all.

But everyday violence looks different, most of the time, and we hardly even notice.

Jessica Valenti made a critical argument regarding rape in The Nation, claiming that “Rape is as American as apple pie—until we own that, nothing will change.”

The same is true for the other forms of violence that we sanction in our communities.

Where is that profound empathy for the children who die because of poverty? For the teens who are more likely to be incarcerated than to graduate from high school? For the seniors who die because of the inaccessibility of medical care?

Where is the empathy that would create wellness in our own very unwell communities?

It’s easier to pretend that we have nothing to do with creating the societal infrastructure that allows violence, so that’s what we do.

We close our eyes to our struggling neighbors. We walk past our homeless brothers and sisters with our eyes on our phones, ignoring the raw humanity and need that is right in front of us, that would make us ache if we would only let it.

But here’s the thing – that ignorance hurts us even more than the pain of seeing such sorrow could hurt us individually.

When we create a culture of coldness, of inauthenticity, of disconnection, we allow violence and hatred to fester.

When we close our eyes to these small acts of violence, we shield our mirror neurons from doing what they are meant to do – we stop ourselves, on a physiological level, from caring for one another.

We stop life-saving communities from growing by starving them from empathy.

But there are ways around that. Here are just a few tips for creating empathy and fostering community.

1. Talk to your neighbors.

Look them in the eye and ask them how they’re doing. And then keep doing it with them and others.

Other options are to throw a neighborhood potluck at your home to help people get to know each other or organize some neighborhood play dates where the parents hang out while the kids play together.

Creating a connection with the people in our own physical communities will create a space for emotional community to grow.

2. Call your friends.

This one sounds silly, but I promise that it will feel better than sending a Facebook message. It’ll feel good to hear your friend’s voice and to have your voice heard.

Do this one enough and it will become habit.

3. Take a personal interest in people.

This is related to numbers 1 and 2, but goes a bit farther. Really make an effort to make someone else feel special for just a brief moment in their day.

When you have the same Starbucks barista twice a week, take a second to learn his name so that you can begin to thank him by name. Ask your coworker about her pets or hobbies, then remember those details and bring them up again later.

Taking a special interest in the lives of the people in our own community helps us and them to feel like their existence matters. Work towards always making people feel important.

To feel truly seen and heard is a special thing, and we should extend that courtesy to the people around us. Who knows, maybe they’ll like it so much that they will try it, too.

4. Meditate

Yes, really. A study has found that meditation helped to increase the part of the brain that holds our capacity for empathy.

Using mindfulness meditation exercises to concentrate on their relationships with their families and friends, participants actually experienced changes in their brains that improved their experience of empathy.

5. Pick an injustice that makes your heart hurt and work to fix it.

Whether it is caring for seniors on your block or saving the stray cats in your neighborhood, find a cause and work toward it.

It doesn’t need to be a full-time career (though great if it is!). As the saying goes, “No one can do everything, but everyone can do something.”

There are tons of organizations that good work and are looking for people to help. Check out Idealist.org or VolunteerMatch for volunteering opportunities.

Not only will you be doing your part to make the world a better place, but you’ll also give yourself a stronger sense of purpose and pleasure.

Please share your own tips in the comments section!

Sarah Ogden is a Staff Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a graduate student in Social Work at the University of Pennsylvania, where she is focusing on clinical work with survivors of trauma, works at a domestic violence agency as a therapist intern, and volunteers as an abortion and pregnancy loss doula. Previously, she’s worked for a suicide and rape crisis hotline and as an emergency room advocate for survivors of sexual assault. Follow her on Twitter @xsogden.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more