Originally published on Womanisms and cross-posted here with their permission.

My mother would never call herself a feminist, even though she is the embodiment of a feminist.

She will say that feminism is incompatible with Catholicism, but warns me of the perils of religious fanaticism; that life is tough for all women, while reminding me she wants me and my sisters to have more opportunities than she did; that she does not have time to protests things she cannot change, although she singlehandedly raised three daughters, working 12 hour shifts as a home attendant for the elderly, six days a week; and that she really wants me to one day get married and give her grandchildren, but there’s no rush!

For many years I thought my mother’s refusal to believe in feminism came from her misconceptions of what it meant. Maybe she was caught up in the whole “lesbian” and “hairy legs” myths that are so often associated with women who are just trying to be treated as equals.

But the reality is that as a Hispanic woman she did not believe that the traditional, Western, view of feminism related to her. Feminism for her felt like a movement she was not entitled to be part of.

Surely women played a major role in the revolutionary movements of the 20th century in Latin America, but those efforts were rarely spoken of in feminist circles. According to history books women’s rights movement of the 19th and 20th century never truly took root in Latin America.

The only way I could understand my mother’s brave streak, while her other female relatives were so deeply entrenched in gender roles and a patriarchal household, was to look at her past, starting with the woman who gave birth to her.

My maternal grandmother became pregnant with my mother out of a love affair in Dominican Republic. My grandfather was already engaged to be married, and he was not going to lose his macho status by being associated with a woman of “lose morals,” so he abandoned her.

Being a single mother is not easy in any part of the world, but Latin America is steeped in conservatism that shames women for being overtly sexual, while exalting men’s promiscuity. My grandmother was shunned from her village, kicked out of her home, and left to fend for herself and her baby daughter.

Ironically, it was my grandfather’s oldest sister, unmarried and in the process of becoming a nun, who took a pregnant woman in. After my mother was born her aunt made sure that her niece was fed, clothed, and educated, and she looked after the woman her brother had abandoned.

Unfortunately my grandmother was never able to get rid of the stigma of being a single mother and the embarrassment of her lover’s abandonment for a more honorable, ie. virginal, woman.

She suffered several mental breakdowns, was hospitalized for neurosis, and in 1970 she committed suicide by swallowing a poisonous cocktail of pills. My mother was raised by her paternal aunt, a woman who was planning on becoming a nun and never expected she would have to be a mother to her brother’s child.

Years later the one thing my mother was certain of was that she was alive, educated, and healthy, none of it had to do with a man. There were no men in her life, except for the few times her biological father would invite her to his immaculate home, where she felt unwanted and out of place.

At the age of 20, my mother married my father. For the first time in her life she had a man in her life, but he was not the prince charming people always told her about. Soon after the honeymoon my father made her quit her university studies claiming her first priority should be her children, he kept her from learning how to drive, and eventually regulated the time she could spend outside the home.

This was exacerbated after we migrated to the United States, by then my sister was born and my mother was pregnant with her third daughter. Now my mother was expected to live by marianismo, the concept that the ideal woman should be spiritually immaculate and eternally self-giving; she is to self-sacrifice and reject her own pleasure in order to please others, particularly the men in her life.

Meanwhile my father lost the status he once had as a married man with children and the owner of his own business in the Dominican Republic. After several failed attempts at opening businesses he drowned in debts, started to drink heavily, and became violent at the slightest provocation. Six years after we first stepped foot on American soil, my parents separated.

The night my mother left we had no where to go. She wandered aimlessly through the streets of Brooklyn, New York with three young daughters and one suitcase. Her nearest relative was on vacation, but it was the only home she could trust. So we sat in her front stoop for hours, although we knew that there was no chance anyone would open the door.

Eventually my mother started looking for a spare key and found it. So we slept in her cousin’s house for that night. It was a house I had visited often, but that night it felt eerie, as if we had broken into a stranger’s home. After unsuccessfully trying to search for a shelter that would take in a mother with three daughters, we went to the house of one of my school mates, whose mother had recently left her husband.

She took us into her tiny apartment and gave us the bedroom of her youngest son. It only had a twin size bed and one window, so my mother would cover the floor with our clothing and lay a sheet over it as a makeshift bed for me and my sister, while she slept in the bed with my baby sister. We did that for six months until my mother was able to finish a training to become an elderly caretaker, get a job, and eventually a new home.

After all of this, my mother was thankful. She says she is one of the luckiest women in the world because she has three great daughters who make her proud. She does not pity herself, she does not even complain.

When talking of the past she says that many have suffered more, and that she would not change anything. Admittedly, when I first began learning of feminism, I became upset with my mother. Surely she had to be angry after so many men in her life had failed her.

How could she not see that she had to become the sacrificial lamb for us, while our father went out at night and did not once have to worry whether his daughters had enough to eat or a place to sleep? How could she work 12 hours a day and still come home to prepare us a meal and clean the house?

I wanted her to be angry, because I was. Why did she have to suffer because of the mistakes others made?

It did not take long for my mother to notice my rebellious streak. One day she had enough of me talking down to her about her inability to see feminism from my point of view. She asked me if I was ashamed of my culture, or if I thought that taking care of children was not a satisfying job; if I truly believed that domestic duties would diminish my worth; and if I thought following traditions were demeaning.

She reminded me that I was the one who insisted on having a quinceañera, the Latin American version of the Sweet Sixteen; a coming of age tradition that included a religious ceremony and my father changing my shoes from flat to heels and presenting me to the world as a woman.

I wanted that, and today I know that it was a patriarchal society that led me to believe my father needed to confirm my womanhood, but I loved it. I will not deny it. It was symbolic and it allowed me to feel closer to my culture.

My mother, the woman that was the definition of marianismo, the unfeminist, was also the woman who taught me to find my own kind of feminism. A feminism that is threefold and includes an attachment to traditional culture, a satisfaction for being a mother and wife, and a devotion to religious symbolism.

My mothers’ feminism was about learning to do better than just survive. She was a full-time worker, a full-time mother, and was fully invested in her community and her church. She did not have the option of choosing between a fruitful career or being a stay-at-home mother.

In fact, I had no working definition of a stay-at-home mom until I was in college, because it was a far-fetched dream in my life. All my female relatives had no choice but to work because not doing so meant their children would go hungry. So they all babysat each other’s children as a way of supporting each other.

I tried hard to make my family fit into the ideal feminist household: a home with two loving and equally working parents who somehow could still make time to be with their children and take summer vacations. But that was idealistic.

My reality was my mothers’ feminism; a feminism that was not just about envisioning a different world, but creating a life that will change it for her children.

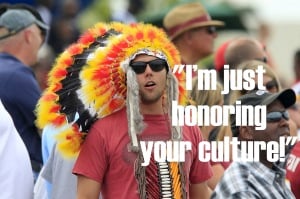

Hispanic women are fully aware that our culture is entrenched in misogyny, but not necessarily any less than American culture. Women in the United States are often expected to take their husbands’ last name. Many men still go to their bride’s father to ask for her hand in marriage; just because we see it as a sweet gesture it does not mean that it isn’t patriarchal in nature.

Valuing your heritage will not take away from being a strong, independent, self-sufficient woman. I feel resentment at the way that Western feminism made me see my mother as a woman trapped in tradition, when in reality she was a living example of a feminist.

Loving tradition and having pride in your culture does not mean these women cannot vocalize the gender issues of their communities. My mother’s feminism was the truest form of feminism for me; a belief in the potential upward mobility of all women.

Feminism cannot continue to exist as a monolithic block, or we will never be able to include women from all walks of life.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Patricia Valoy is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Civil Engineer, feminist blogger, and STEM activist living in New York City. She writes about feminist and STEM issues from the perspective of a Latina and a woman in engineering. You can read more of her writings on her blog Womanisms, or follow her on Twitter @besito86. Read her articles here and book her for speaking engagements here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more