Originally published on Adios Barbie, and cross-posted with their permission.

Credit: “Don’t Speak” by Kristin Schmit

Writing doesn’t scare me. Bats circling over the roof of my house scare me. When the spider crawling across my desk suddenly disappears and I have no idea where it went, that scares me.

Writing? I’ve got this.

But looking at my blank screen while trying to write this post, I was terrified. I’ve barely said these words to anyone.

I dealt them out on a need-to-know basis. My parents, then eventually my best friend, my roommate: these people, I reasoned, needed to know.

Why would I tell anyone who wasn’t directly affected by it, and who would only see me differently because of it?

But I can’t keep this secret to myself anymore.

How am I supposed to fight against the stigma that drives sufferers into shame and silence when the thought of writing out one measly sentence makes my heart beat faster than if I’d drunk six cups of coffee today instead of two?

I can’t. I can’t keep pretending that the ideals I’m laying out to the world don’t apply to me. And so here it is, my “coming-out” post.

I’ve been fighting anorexia since I was 16.

There.

I don’t know if that sentence is glaring at you off the screen like it is to me, but there it is…No going back now.

I’d like to pretend that this is a surprise for those who know me, but I’m not sure how many people already guessed. It’s said that anorexia is a disease of isolation, and from my experience, there’s a lot of truth in this.

My friends and family couldn’t have failed to notice how much I was disappearing, both in body size and physical presence. After years of avoiding meals with friends, exercising as much as I could and hating every second, checking the number on the scale that was never, never, never good enough, I’ve reached a place where I feel safe enough to speak out honestly.

I’m not going to pretend that now I spend my days prancing through a field of flowers with classical music playing in the background, but the way I think about it, I’m in the process of kicking my ED to the curb.

Sometimes it trips me up, and I have to go home, curl up in bed, and feel sorry for myself for a few hours. But most of the time, I can spit in its general direction and keep walking.

The fact is, there is no perfect recovery. Even if that insidious voice that says, “You’re not good enough,” crawls into my mind again and yells at me because of what I ate for dinner, that doesn’t mean I’m failing in recovery.

Thoughts and behaviors are not the same thing. Just because sometimes I’d like to fall back on my unhealthy coping mechanisms doesn’t mean I’m doing it.

And even if I do slip occasionally, that doesn’t mean I’m giving up. Mistakes are part of every journey that’s worth taking, and recovery is no different.

It’s not gone. I can’t be completely sure it’ll ever be gone. But I do get a little bit of satisfaction every time I can look it in the eye and say, “You know what? No.”

I’m not writing for sympathy or attention. I’m writing in the hopes that my honesty will help break down the stigma that kept me staring at a blank page for twenty minutes, wondering if the other people sitting around me in my favorite coffee shop were reading over my shoulder and passing judgment.

Eating disorders fall into that catch-all category of mental illnesses that are not socially acceptable to talk about. We get uncomfortable when someone brings them up, like they’ve suddenly pulled their pants down in public.

Hearing someone say, “I have depression,” or “I have bipolar disorder,” or “I have binge eating disorder,” gives us the excuse to view them exclusively through the lens of that disease.

Oh, she just shouted at that guy who cut her off in traffic? Well, she is bipolar. Or: don’t ask her over for dinner, she’s anorexic.

No. I had anorexia; I was not an anorexic. It was something I dealt with, not something I was.

Would you call someone with cancer “cancerous?”

Adding this stigma to the already-twisted self-image of people with eating disorders only worsens their feelings of shame, guilt, and secrecy.

Isolation becomes a coping mechanism not only because it’s the only sure way to avoid triggering situations, but also because opening up to others usually creates the “rubberneck syndrome.”

Instead of providing a net of support, people whisper behind their backs and constantly feel the need to ask them if they’re okay.

Yes. I’m fine. Please look at me like a human and not the word “anorexia” with arms and legs.

Of course, there are resources available for those struggling with eating disorders: check out the first in a series of posts outlining treatment options here.

But it’s impossible to be in therapy every time an urge to use disordered behaviors pops up, short of inpatient services, which may only make the pressure to be the thinnest person in the room even more difficult.

Therapy is wonderful, but it requires a patient-doctor relationship and a level of mutual trust that I was never able to find. Nutritional therapy won’t help without the mental strength to deal with the negative thoughts that can come with a change in behaviors and body weight.

No one should have to fight an eating disorder without help, but disappointment after disappointment while searching for support can make the battle feel incredibly lonely.

What we need while recovering from an eating disorder, says research and say the 7:00 p.m. calls to my parents I used to schedule my nights around, is real-life, real-time support.

Someone you can turn to when you’ve had a terrible day, when the urge to use behaviors of any kind is too strong, when you’ve been holding your emotions in for what feels like (or really has been) years and need someone to be your sounding board while you punch pillows and yell.

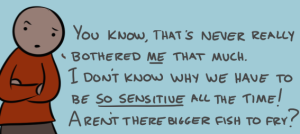

But the fear of being judged or written off as “narcissistic” or “self-absorbed” or being told to “just start eating normally and get over it,” forces too many people into silence.

And silence is the least helpful thing you can put in your recovery toolbox.

Because the truth is: eating disorders are not “first world problems.” They are not overly-successful diets. They do not reflect on your history, intelligence, or appearance, and they are not evidence of narcissism or shallowness.

They are mental illnesses, and they can strike anyone.

People from all ethnic backgrounds, any gender and any sexual orientation, all around the world, any socioeconomic status and any religion, any age, any body type, and any weight, can suffer from the self-loathing, self-destructive behaviors, and distorted self-image that are symptomatic of eating disorders of all kinds.

The DSM-V, the go-to dictionary of psychological disorders, recently updated its definitions of eating disorders in order to reflect this diversity, which is a step in the right direction. For instance, amenorrhea, or the loss of regular menstrual periods, is no longer a requirement for a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.

Beyond addressing that girls struggling with body dysmorphia and disordered behaviors were being told they weren’t thin enough to have an eating disorder (what part of this was supposed to be helpful?), this opens up the door for the recognition of eating disorders among men as well.

But all the research and redefinitions in the world won’t do anything if sufferers are too afraid and ashamed to seek help. If I caught the flu, I’d tell my doctor, take medicine, drink some ginger ale, and stay in bed.

When I had anorexia nervosa, I didn’t tell my doctor because I was too ashamed to tell a medical professional that I had a medical condition that needed medicine and physical and mental treatment. I was afraid that my own GP would judge me.

Can you blame me, when “anorexic” is an insult splashed across tabloids?

I don’t deserve to be treated differently. All I want is recognition that the battles we’re fighting each and every day are legitimate and deserve attention without stigma.

My illness is not a joke or an insult. Those whose struggles are similar to mine, or whose silence has been similar, deserve the chance to speak out.

If you’re struggling with disordered eating or negative body image, don’t be afraid. Tell someone. Start with someone you love, who you know will never judge you. They might not understand completely, but let them know that they don’t need to know what to say.

All we really need, sometimes, is someone to listen. Tell your doctor. Tell your dog. Tell yourself in the bathroom mirror. Write it down on a piece of paper and read it out loud. Start by putting it in the world outside of your head.

Because if we can’t support each other out loud, all we’ll do is suffer in silence.

Want to discuss this further? Login to our online forum and start a post! If you’re not already registered as a forum user, please register first here.

Allison Epstein is a Writing/Publishing Intern at Adios Barbie and is a current undergraduate at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor studying English, creative writing, and French. An aspiring writer and novelist, her first novel is Na Zdarovye, a historical Russian romance, and she is the author of the blog The Body Pacifist, where she discusses recovery from eating disorders, gender-conscious media literacy, and the occasional song-and-dance routine. Follow her on Twitter @AllisonEpstein2.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more