Source: Start Up Law Blog

Not too long ago, I got an angry e-mail from someone in the town where I grew up.

The author of the e-mail is someone who knows my parents pretty well, and he had somehow stumbled across something I had written about privilege.

“How disrespectful can you be!? It’s like your spitting in the face of everything your parents have worked for,” he wrote. “Writing about this White privilege makes it look like your father, one of the harder working men I know, just had everything handed to him. You know that’s not the case!”

I did my best to respond by explaining that privilege doesn’t necessarily mean that you’ve had everything handed to you, and I know that my father has worked hard. To say that we have privilege doesn’t discredit any of his hard work. It simply puts that hard work in context.

I recently heard privilege described as a “tailwind,” taking your effort and energy and propelling you further forward than those who must fly against the winds of our society’s constructs of power and privilege.

My father didn’t grow up with incredible wealth privilege. He is the son of a truck driver and stay-at-home mom who also worked at a local school cafeteria to earn extra cash. My grandfather grew up in the “holler” in West Virginia in an area well familiar with intergenerational poverty.

Part of what set our family apart, though, was our ownership of land.

Similarly, on my mom’s side of the family, go back a few generations and you’ll find some poor, hardworking farmers from Ireland and Belgium who settled on stolen indigenous land in South Dakota. Again, they were able to buy a plot of land upon which they could start to build their familial wealth legacy.

Fast forward a few generations, and I am the son of a doctor and a nurse.

Wealth and the Context of History

There are really a few ways to look at my family’s history.

Some might say that it’s the perfect example of “The American Dream,” as defined by the ability of a people to build something (read: wealth) for themselves that is passed down to ensure the next generation’s life is a little better than the last.

Others might note that my family’s story perfectly illustrates the trappings of privilege.

Sure, my family gave up most of our cultural identity to become White in the United States, but doing so gave us access to a system that privileged us in countless ways.

Simply put, we traded culture for a tailwind.

After all, one of the key markers of access to wealth in the United States for much of its history has been the ability to own land. There’s a reason that for a good, long while in this country, a man couldn’t vote unless he owned land, and you couldn’t own land unless you were White and Christian.

And land-ownership has been systematically denied to those not considered “White” (through the ever-changing construction of Whiteness) for most if not all of this country’s history.

From the Land Grant Acts to the Homesteading Acts to redlining policies to White flight, we see how owning land, but particularly land considered “desirable” or worthy (whether because of access to resources or proximity to jobs or simply status) allows for wealth mobility.

And this access to wealth mobility is relates directly to intersectional identity politics.

This does not mean that all White people are wealthy or that poor White folks somehow are failures for not better working the system that privileges us.

It simply means that the limited access to wealth that has always been a staple in this country has just been more limited for people of Color and women and disabled/differently-abled people and non-Christians and really anyone who isn’t part of the smaller, privileged few that are most granted access to wealth in this country.

Income vs. Wealth

In the discussion of this problem of access lately, I have seen a lot of conversations about “wage gaps” and income disparity and the like.

And we absolutely need to have those conversations, as in a capitalist society, the amount we pay a person for their labor tells us a lot about where we stand in terms of equity (though we can and should problematize that framework).

But income is only part of the picture.

As Jarune Uwujaren laid out well, talking about inequality means talking about wealth, and wealth is different from income.

Wealth, in essence, is the summation of all of our assets minus the debt we hold. Wealth is the cushion we have available to us when things get rough.

I, for instance, don’t get to inherit my dad’s job simply because I’m his son. Considering that he’s a doctor, that would be terrifying! But if my dad wants to pass it down, I can inherit his wealth (split three ways since I have two sisters and we now allow inheritance to be transferred to women rather than to their husbands).

Hence, someone who descends from relatively poor, immigrant farmers in South Dakota can be in a position to inherit great wealth privilege: wealth, in general, accumulates from generation to generation.

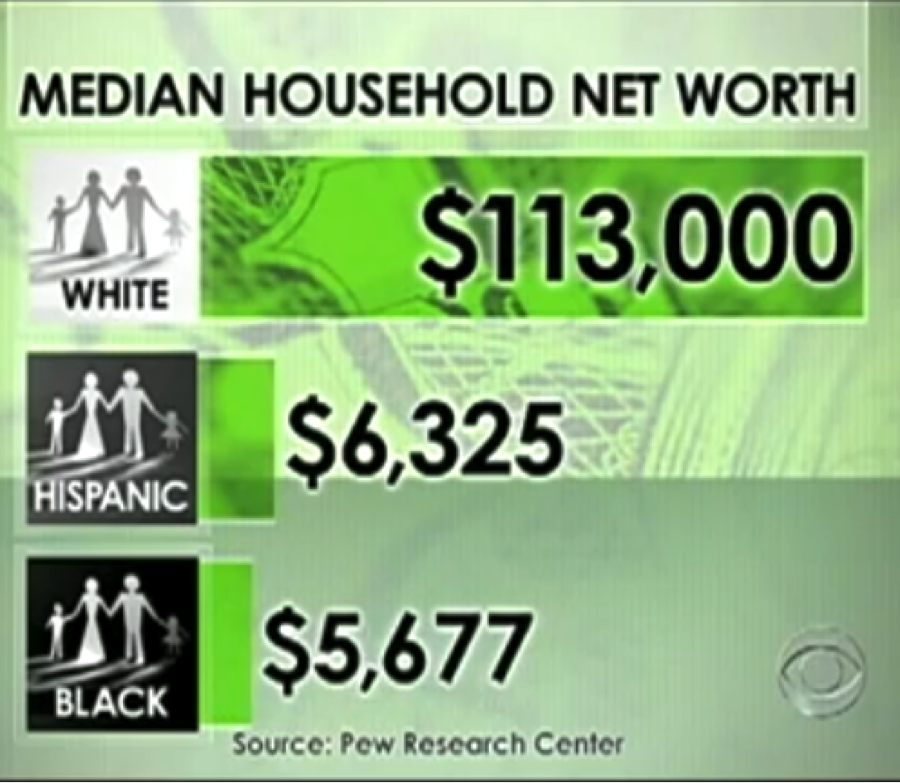

Thus, while gains have been made in closing wage gaps over the last fifty years, the Pew Research Center reports that the wealth gap is the worst it’s been since the U.S. government started keeping track, with the median household wealth of a White family being eighteen times higher and twenty times higher than that of Hispanic and Black families respectively.

Source: CBS News

What this means, then, is that even for the most prudent, fiscally-minded family, in the event of a major economic event (such as a lost job or major medical bill), the average White family has a significantly larger cushion than the average Black or Latino family in the U.S..

Thus, when the “Great Recession” hit, who was most greatly affected? People of Color – most notably, single mothers of Color.

Yet all of our mythologies and narratives talk about wealth as if it is completely an individually driven reality.

Thus, much of the commentary and commenting being done across the Internet in response to this startling study has been placing blame on Black and Hispanic families for (among other things) not saving enough or for being too lazy (despite the fact that White and Black families save at the same rates).

Demonization of Redistribution of Wealth

What this focus on individuals ensures, then, is that we avoid talking about wealth at all (particularly among those with wealth), and we get to avoid actually dealing with structural inequality.

Sure, there might be the rare “self-made person” who is lauded as the perfect example of “pulling oneself up” in our society, but for the vast majority of us, that is statistically impossible.

But to acknowledge that we can’t all be a hero of a Horatio Alger novel means that we might need to actually address why upward mobility is difficult in the U.S. and is more difficult for some people than for others, largely as a result of the history that informs our present.

Hence, we demonize the concept of wealth redistribution.

But if we want to realize social justice, then we need to address talk about more than individual people pulling themselves up by their bootstraps.

Redistribution of wealth is vital to social justice work because it challenges the very system of intergenerational privilege upon which everything in capitalism is built.

But as Tal Fortgang, the privilege-denying dude from Princeton, bemoaned in his letter (that was infuriatingly elevated to the platform of Time Magazine):

“When we similarly sacrifice for our descendants by caring for the planet, it’s called ‘environmentalism,’ and is applauded. But when we do it by passing along property and a set of values, it’s called ‘privilege.’”

It’s most definitely not a bad thing to want to pass down one’s wealth to one’s children, but considering the disproportionate access to wealth in this country both historically and today, to have wealth to pass down is the literal definition of privilege.

But to actually name that is to spit in the face of the widely-believed American mythology of meritocracy.

So what are we to do?

After all, I, too, want to ensure that my kids have a great life; I just don’t want to do that while furthering the marginalization of other people’s children.

Start by saying it with me: Redistribution of wealth is a good thing.

4 Things You Can Do to Redistribute Wealth

For some of us, acting in class solidarity and tackling wealth inequity can’t and shouldn’t mean redistributing our own wealth. For others of us, we must consider ways that we can responsibly participate in the redistribution of our wealth.

But it can’t just only be the actions of individuals giving of their own wealth that will transform this problem. It must be a combination of concerted activism of individuals leading the way to better public policy.

Regardless of how it’s done, one of the keys to effective wealth-transformation activism is that we cannot simply rely on the same paternalistic models for “helping” low-wealth people.

Too often, even the most well-intentioned efforts are simply those with access to wealth inviting individuals into the club on the terms of the wealthy.

Thus, while there are innumerable ways to tackle wealth inequity and to aid in the redistribution of wealth, here are a few of my suggestions:

1. Participate in Movements for Living Wages and Benefits

Ideally, we wouldn’t have to participate in the cat-and-mouse game of wage raises and would live within an economic system that didn’t rely fundamentally on the exploitation of the cheapest possible labor.

Unfortunately, until we realize a different system, fighting for basic worker’s rights is fundamental to wealth transformation.

Obviously, as covered above, wages are not the key to wealth, as there are bigger issues at hand that ensure disparity, but wages and benefits provide for the stability that allows us to fight for other public policy changes.

Whether we’re fighting to raise the minimum wage or for universal healthcare or for living wage ordinances in our hometown, we need to stand together demand that each person is paid more than the bare minimum to survive.

What this means, though, is that in a global economy, our activism for economic justice can’t just be within our own borders. Capitalism drives a race to the bottom, and if another state or another country allows employers to exploit laborers, the problem just moves next door.

Thus, whether it’s taking to the streets to support your local union or lobbying against NAFTA, we have to find our place in the movement for living wages and benefits.

2. Advocate for a Progressive Inheritance Tax

Republicans in the 1990s effectively repealed or rolled back many of the most progressive inheritance or estate taxes through a concerted public imaging campaign, calling them “death taxes.”

Inheritance and estate taxes, though, are key to effectively battling the disparity in wealth that is a legacy of sexist, racist, ableist, and otherwise oppressive policies and practices of our past.

By taxing the inheritances of the wealthiest among us, we ensure that wealth does not remain solely consolidated in the same hands that have always had access to wealth.

However, inheritance and estate taxes do nothing to redistribute wealth if the tax dollars collected just go into the general public coffers.

Thus, we need to advocate for a progressive tax that earmarks inheritance/estate dollars for scholarships for low-wealth students or to support public schools in our lowest-wealth neighborhoods or even for direct reparations to families of those held as slaves or exploited in mines or forced off their land.

Such progressive public policy won’t be easy to pass, but it’s vital to transformation of our wealth landscape.

3. Support Policies and Programs that Trust Low-Wealth People

Pervasive in many of the movements to “help” low-wealth people access systems and resources is the incredible classism of “Well, you clearly don’t know what’s best for you or you wouldn’t be poor!”

Yet there’s plenty of evidence to tell us that most people know what’s best for themselves, and people who don’t have access to great wealth are no different.

Thus, no matter our wealth situation, we can support and advocate for wealth-transformation approaches that trust and empower low-wealth people.

At a public policy level, homelessness could be eliminated in Utah (a staunchly red state nonetheless) by 2015 thanks to public policy that simply gives people experiencing homelessness a place to live, no strings attached.

Those advocating for the policy recognize that offering homes not only costs less than alternatives, but some of the primary supporters have noted that people can begin to address struggles in their lives better when their primary needs are met.

In the private sector, a program known as GiveDirectly has found great success in simply giving money to those who need it.

“Researchers found that children in the cash program were more likely to stay in school, families were less likely to get sick and people ate a more healthful diet . . . and many even invested a chunk of what they received.”

Contrary to some of the negatives found in microlending, programs that offer low-wealth people what they need, no strings attached, have, thus far, been pretty darn successful.

4. If You Have Wealth, Redistribute Accountably

Finally, for those of us who have wealth, we have a responsibility to redistribute what you can.

This always gets tricky, as people will often say to me, “Why should I put myself out on the street in order to help others.”

Obviously, that’s not what I’m calling for (unless that’s how you’re moved). Clearly, we can and should take care of ourselves and our families. But when we have excess wealth, what are we willing to sacrifice to help redistribute wealth toward social justice ends?

There are some great models out there to lead the way.

JLove Calderon and Tim Wise call on White people who profit from White privilege discourse to donate a portion of their profits to social justice organizations led by people of Color, offering a model for White accountability in wealth redistribution.

Resource Generation, an organization of people with wealth privilege, offers models and methods for young people with access to wealth privilege to partner with organizations and causes that need financial support.

Not everyone will be able to give in the same ways or the same amounts, but if those of us who can redistribute our wealth commit to doing so, our collective impact can be tremendous.

Bring Wealth Disparity Out of the Shadows

In all of this, we have to change the way we talk about wealth, both in public discourse and in our personal lives.

If your family is anything like mine, when you brought up money, you were shushed, told “It’s rude to talk about how much money you have.”

We have to change this reality.

So long as we don’t talk about wages, we can’t expose racist and sexist and ableist disparities in pay.

So long as we don’t talk about inter-generational wealth, we can’t talk accountably about what redistribution looks like.

But when we bring the wealth conversations out of the shadows, we take an important step to addressing the disparities that so greatly hinder our efforts toward social justice.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Want to discuss this further? Visit our online forum and start a post!

Jamie Utt is a Contributing Writer at Everyday Feminism. He is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Minneapolis, MN. He lives with his loving partner and his funtastic dog. He blogs weekly at Change from Within. Learn more about his work at his website here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more