Source: Mind Out Conference

Imagine this situation: A classroom of students is settling down to work on a writing task. All of a sudden, one student exclaims, “That’s not fair! Why do they get to listen to the instructions on the headphones! I want to listen, too!”

This happens way more often than you think. Not because teachers are inherently unfair creatures (I would know; I’m a teacher), but because students have come to understand “fairness” as simply equal treatment.

You’re familiar with this playground mentality of fairness: “I get two crackers, and you two crackers” or “I play with the ball for twenty minutes, and then you play with it for twenty minutes.”

Others are starting to question this “Sharing is Caring” idea and over-simplistic expectations of fairness.

Because here’s the thing: Treating everyone exactly the same actually is not fair. What equal treatment does do is erase our differences and promote privilege.

Let me break it down.

Teaching middle and high school students taught me all I needed to know about fairness and the persistence of privilege. Here are the two main lessons I learned.

1. When Everyone Is Different, Fairness and Success Also Differs

An important conversation I have with my students is around the idea of equity versus equality. What do “fairness” and “success” really mean when we know that everyone is so different?

Equity and equality are two strategies we can use in an effort to produce fairness.

Equity is giving everyone what they need to be successful. Equality is treating everyone the same.

Equality aims to promote fairness, but it can only work if everyone starts from the same place and needs the same help. Equity appears unfair, but it actively moves everyone closer to success by “leveling the playing field.”

But not everyone starts at the same place, and not everyone has the same needs.

Classrooms, for example, are made up of different learners. This means that students enter the classroom with different learning styles (such as visual, auditory, or tactile). You can take this short quiz to figure out your own learning style.

Visual learners and auditory learners will process information differently and, thus, have different needs. If the teacher always lectures, auditory learners have the advantage.

So it doesn’t matter that the outraged student wants to listen to the audiotape to complete the writing task. What matters is whether the student needs to listen to directions on an audiotape in order to be successful with the writing task.

Since everyone is different and we embrace these differences as unique, we must also redefine our basic expectations for fairness and success as contingent upon those individual differences.

In the real world, this means that some people will need a language translator when speaking to a government agency and others will not. And it wouldn’t be fair to just provide Spanish translators just because it is the language most people speak. A Spanish translator would not allow a Korean speaker the same access to opportunities.

That would be privilege.

Privilege is when we make decisions that benefit enough people, but not all people. Privilege is allowed to continue when we wrap it up with actions of equality.

On the outside, everything appears fair, because how can we argue against equal treatment? When we uncover the equality blanket, we see that not everyone’s needs are met.

Take gender for example.

Fairness between genders doesn’t mean that everyone should become the same. The end goal is not for men and women to reach a complete genderless state. It means that men and women should be given the same opportunities to succeed despite their differences. Check out the United Nations Population Fund for more on gender equality.

We need to recognize our differences as unique, rather than reach for one definition of “success.” By upholding just one definition of success, we actively erase our differences. Our differences are not the obstacles.

2. We Need to Engage in Equitable Practices

Fixing the systematic obstacles (rather than fixing individual differences) requires us to be more intentional, but the extra work pays off.

If we cannot blame our differences, then we must look to systematic obstacles. Would we assess a fish’s success by its ability to climb a tree? No way. In fact, Albert Einstein once claimed that “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” So why do we insist on administering the same test in the same paper-pencil format to a classroom of diverse students?

As a teacher, this means I must reexamine my classroom system to allow all my students to reach success. My system has to change. I must, yes, think about every student, because my class must help every student learn.

This is called “differentiated instruction” in the classroom, and we need it in the real world, too. We need to recognize the needs of individuals and change our actions to fit those needs.

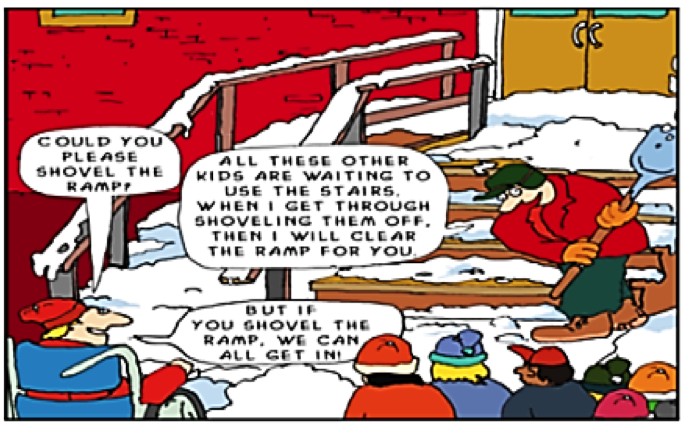

Take a look at the cartoon below.

Source: Peytral Publications

This teacher is diligently shoveling snow off the stairs to allow the majority of the students to get inside the building. Instead of shoveling snow off the stairs first, the teacher could shovel the ramp to allow all students access – not just abled bodies.

This is worth repeating: “But if you shovel the ramp, we can all get in.”

Often times, decisions are made to benefit the majority of people without paying attention to individual needs and nuances. Instead of gender-specific restrooms, we could offer gender-neutral restrooms to allow everyone access to restrooms – not just those who fit within the men or women boxes.

Privilege is a tricky thing.

I’m not aware of my privilege on a daily basis – no one is. I don’t get up in the morning and wonder if I will “pass” because I am a cisgender woman who generally loves her body. I don’t feel a bit of my privilege when I sit in an hour-long lecture because I don’t have any learning needs or when I’m asked which college I graduated from or when I walk up a long flight of stairs. (I just feel pain in my calves. Oh, my life is just terrible, because the escalators are broken again.)

Usually I am just unaware of my own privilege, because the system generally works in my favor.

What does the other side of privilege feel like?

Jeremy Dowsett says it feels kind of like riding on roads built for cars. For a biker, the roads are dangerous. Not intentionally. Most drivers aren’t trying to be jerks. It’s just that the traffic rules and road system simply wasn’t made to work for both cars and bikes to coexist peacefully. Cars and bikes are different. And the truth is that “the whole transportation infrastructure privileges the automobile.”

So the system is flawed when it does not meet everyone’s needs.

Can we change the whole system? Rarely. What we can do is advocate for equitable practices in order to promote fairness. This requires extra work.

In the classroom, I will lesson plan for different students’ needs and learning styles. I will design stations that allow for use of technology, exploration, traditional book work, and even art – which can (and should) be done for all levels. The extra work is worth it because the key is to allow everyone to succeed. I need to practice equity in order to truly be fair.

We can no longer rely on blanket practices just because they appear fair. Our actions actually have to elicit justice.

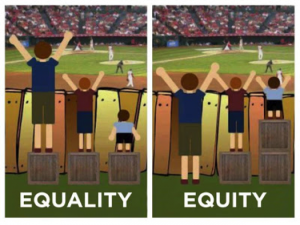

Take a look at this famous cartoon regarding equity and equality.

Source: Out Front Minnesota

Each child is of a different height. We can’t change that. In order to insure that every child has access to the baseball game, we can provide them with boxes to stand on.

But we can’t just bring one-sized boxes to lift everyone up. That’s equality, and equality does not always elicit true fairness. We need to put in the extra work and give everyone what they need.

***

The first step to justice is being able to recognize it. Do you know the difference between equity and equality? Test yourself here.

Audre Lorde maintains, “It is not our differences that divide us. It is our inability to recognize, accept, and celebrate those differences.”

So look around you. What differences do you notice? And how can you incorporate these differences into the everyday decisions you make?

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Amy Sun is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She has worked with providing resources and support for Asian/Pacific Islander survivors of domestic violence in the DC, Maryland, and Virginia areas. She also holds her Masters in Women’s Studies from the George Washington University, where she has researched the coming out processes for trans* who identify as FTM and MTF.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more