Source: Weekly News

“She doesn’t make a good witness.” I will never forget those words.

I know there had to be previous examples of discrimination that occurred in front of me toward a person who had a physical or mental disability, but this was the first one that made me take a serious look at my privilege as an able-bodied person.

It took seeing a survivor of a violent crime being told that she would never see justice because her disability didn’t allow her to express herself in a way that an attorney thought would be believable.

Correction: She wasn’t told this; the attorney said it to me even though the survivor was sitting right there. Why? Because I don’t have a noticeable disability, and it was assumed that the survivor wouldn’t understand.

Well, she did. She understood that she was getting screwed.

What does this example have to do with hate crimes against people with disabilities? Everything.

This scenario describes the common experiences of many people with disabilities who have been victims of hate crimes: They were targeted because of their disability, false assumptions were made about their capabilities, they were discredited because of their disability, and “the system” seemingly did nothing.

Before I continue, I must mention that much of the research and ideas that I will express do not originate from me. I draw upon the knowledge of researchers, advocacy organizations, and the expertise and experiences of people with disabilities.

As a person with able-bodied privilege, I can’t speak to these experiences. But I can engage other able-bodied people and encourage them to avoid ableism and advocate for people with disabilities.

What Is a ‘Hate Crime?’

Congress defines a hate crime as “a criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by the offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, ethnic origin, or sexual orientation.”

Specifically, the Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 (also known as the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Act.) criminalizes violent acts upon people with disabilities and other classes.

And while it’s great that these federal hate crime laws exist, it may be of little help if the state you reside in does not have disability listed in their own hate crimes legislation. (You may want to check out your state.) In such cases, the offender who commits an act not listed (e.g. assault) will likely get a much lighter sentence than if the hate crime enhancement were added.

Since hate crimes are covered under federal civil rights legislation, states that don’t cover them should report such allegations to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which does investigate hate crimes. But that doesn’t always happen.

This means that a hate crime may or may not be viewed as a hate crime depending on which state the victim is in. It may or may not be prosecuted as one. It may or may not be reported to the FBI. And it may or may not lead to a conviction.

A current events example where this may occur is the fake “Ice Bucket Challenge” crime that took place in Ohio. A 15-year old boy with autism was misled to believe he was going to participate in the challenge, only to have a bucket of urine, feces, and cigarette butts dumped on his head. The teenage boys responsible for this will likely not face a hate crime enhancement because Ohio doesn’t have hate crime laws that protect people based on disability.

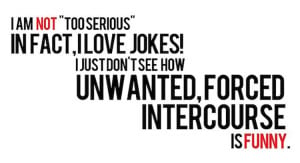

Does Anyone Really Hate People With Disabilities?

Data regarding hate crimes against people with disabilities was not collected under the original Hate Crimes Statistics Act (HCSA) of 1990, and some suggest it is because many people didn’t believe that hate crimes against people with disabilities existed.

I mean, nobody really hates people with disabilities, right?

Wrong.

This is important to realize because the failure to believe this is one reason why it’s a hidden problem.

Dr. Mark Sherry’s book, Disability Hate Crimes: Does Anyone Really Hate Disabled People? provides multiple examples of hate toward people with disabilities and describes vile crimes that meet the criteria of a hate crime, but will never be prosecuted as such, and often times are not prosecuted at all. If they are prosecuted, they are likely pled down to some insulting infraction that results in little punishment.

The Internet has numerous sites devoted to hate speech against people with disabilities that call for their abortion, torture, and murder. Just Google any combination of ableist slurs and the word “hate” if you don’t believe me.

Hate crimes are usually more violent than non-bias crimes, and victims of hate crimes are three times more likely to require hospitalization. They are more likely to have multiple assailants, and there is evidence that shows that victims of hate crimes experience significantly higher levels of psychological distress than victims of non-bias crimes.

Statistically, people with disabilities are:

- Three times more likely to be a victim of a serious violent crime (rape or sexual assault, aggravated assault, and robbery) than people without disabilities

- Twice as likely to be a victim of simple assault than people without disabilities

- More likely to be victimized if they have more than one disability

- More likely to be victimized regardless of race or gender than their non-disabled counterparts.

Compared to non-disability hate crimes, rape is 30 times more common in hate crimes against people with disabilities, and they are much more likely to be a victim of a simple assault. Hate crimes involving burglary and larceny are also more common against people with disabilities than in non-disability hate crimes.

Hate crimes against people with disabilities frequently involve dehumanizing acts and speech. Situations that include urinating and defecating on victims are not uncommon, so the scenario with the “Ice Bucket Challenge” is not an isolated event.

In addition, people with disabilities, particularly people who have mental disabilities, are frequently lured to their own hate crime under the guise of friendship.

So, yes, some people do hate people with disabilities.

Hate crimes against people with disabilities are notoriously underreported, and the fear of retaliation is great. In fact, compared to other types of hate crimes, the victim of a disability hate crime is more likely to know their offender, which makes them more vulnerable.

Americans with disabilities are also more vulnerable to hate crimes because they are statistically three times more likely to live in poverty than people without disabilities. Low-income means they are less likely to own their own home or vehicle, and more likely to reside in rented property or institutional settings while utilizing public transportation.

People with disabilities are less likely than people without disabilities to socialize with others, so they are more likely to be put in situations where they are exposed, isolated, and unable to escape at will.

This is a serious problem. So how can we work to solve it?

What You Can Do

1. Check Yourself

If you are a person with able-bodied privilege, it is important to realize it and decide to get involved in helping to combat ableism.

Everyday Feminism has two articles that will help get you started: 10 Ways to Avoid Everyday Ableism and So You Call Yourself an Ally: 10 Things all ‘Allies’ Need to Know.

Become familiar with resources for people with disabilities. Disability.gov is a good place to start.

2. Demand Justice

Are disability hate crimes covered in your state? If not, write your legislators. If they are covered, are they being enforced?

Support legislation that helps people with disabilities by improving access to services, closing financial disparities, and increasing resources.

3. Start an Awareness Campaign

Raise awareness in your workplace, home, or school.

If you have children, talk to them about respect for people with different kinds of abilities.

4. Always, Always, Support a Survivor

Reporting these crimes is difficult. There are a number of barriers that can prevent a person with a disability from seeking justice. Offer assistance whenever possible.

***

A disability that was exploited during a hate crime is the same disability that’s supposed to afford the person protection under the law. And so it is nauseatingly ironic that our legal system betrays some people by using this disability against them,

But it is not just the legal system.

Our entire society devalues people with disabilities by the daily reminders that everything around them is set up with the able-bodied person in mind, and there are countless examples of cruelty.

Because of this, we all play a role in generating a culture that harms them and then looks the other way.

As an able-bodied person who has not lived the experiences that people with disabilities have, it is very possible that I may fall short in my attempt to advocate on this subject. It is for that reason that I more than welcome suggestions or challenges from anyone who can advance the awareness of this problem.

What are your thoughts and ideas?

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Dr. Robin Landwehr is a mental health counselor and an unapologetic feminist. She holds a Doctor of Behavioral Health degree from Arizona State University, a M.S. degree in Mental Health Counseling from Capella University, and is a licensed counselor in North Dakota and Florida. She is a National Certified Counselor through the National Board for Certified Counselors. Robin has worked in several areas of human services including: domestic and sexual violence, substance abuse, homelessness, child abuse and neglect, mental health disorders, and health concerns that are affected by our behaviors. You can follow Robin on Twitter @RobinLandwehr1 or visit her sometimes neglected personal blog at the Hippie in Me Blog.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32