Editor’s Note: On 10/6/2014, The Seattle City Council voted to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day – yay!

October sixth will be a historic day.

Not historic like discovering things, but historic like huge, positive impact on a group of people marginalized for centuries.

Tomorrow, the Seattle City Council will officially vote to replace Columbus Day – celebrated the second Monday of October – with Indigenous Peoples Day.

The council delayed the vote from one scheduled in early September in order to better educate the public on its reason for the change, and also to allow Mayor Ed Murray to sign a declaration on the thirteenth.

Of course, there’s a chance the vote won’t come.

Of all people, we Native folks understand the—uh, complexities—of political promises. Hundreds of years of broken treaties have given us a fine dose of realistic pessimism.

However, like many Natives and allies, I am wholly optimistic and eagerly anticipating tomorrow’s vote in Seattle, if only because the national conversation is finally recognizing Columbus Day as the annual gut punch it is for indigenous people.

By all accounts, including his own journals, Christopher Columbus was not a cool dude. At best, he’s an explorer who got lost and got famous for it; at worst, he’s responsible for the introduction of slavery, human trafficking, and genocide in the New World.

And yet, primary schools across the country continue to celebrate someone who would be considered a terrorist in modern times.

As a kid, I recall that horrid 1492 rhyme and coloring pictures of the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria. Those lessons never included information about the people indigenous to the land Columbus came upon – not what is now “America,” or Asia, as he had hoped, but the Bahamas.

And it rankles that my own kid continues to be force-fed false history that delegitimizes and erases her heritage (and I do talk to her teachers beforehand, but habits are hard to shake, especially the bad ones). It’s lazy teaching, plain and simple. This is 2014, folks. We can do better.

And that’s why tomorrow’s vote in Seattle is so pivotal: As cities and states around the nation begin listening to indigenous voices, our issues are finally – finally – getting the attention they deserve.

That’s not to say that Columbus and his impact shouldn’t be discussed; on the contrary, schools should teach about the various contacts outsiders made with indigenous nations, the outcomes of those contacts, and how those experiences impact people today.

The discovery myth surrounding Columbus needs to go and, like the holiday, be replaced with more accurate information that incorporates indigenous perspectives.

With this in mind, the four strategies listed below will help teachers, youth workers, and anyone interested in learning and sharing legitimate history:

1. Develop Historically Accurate Lesson Plans

With the Internet, there’s no excuse whatsoever to be teaching defiled, whitewashed, and fabricated history.

Luckily, recreating the wheel is unnecessary. Plenty of folks have dedicated massive amounts of time to ensuring primary school students receive the best education possible.

The state of Montana and its Office of Public Instruction paved the way with its “Indian Education For All” concept, which has provided culturally relevant instruction for all public school students (not just the Native kids) since 1999. Check out the link provided for resources, lesson plans, and success data.

My home state of South Dakota used Montana as a model when the Sioux Falls School District developed its Native American Connections curriculum, which includes Lakota language instruction, star knowledge (astronomy, not astrology), and origins of the Očéti Šakówiŋ (or Seven Council Fires, what most people erringly refer to as the Great Sioux Nation – the word Sioux is problematic, but that’s a different post for a different day).

I was part of an early curriculum development committee and was impressed with the inclusion of not just Native history, but contemporary issues relevant to today’s Native youth. The South Dakota Office of Indian Education also has some great links for educators to use and share.

Other states – mostly with large Native populations, including Washington, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and New Mexico, among others – have been using similar curriculum for decades, although much of it is specific to increasing the success rates of Native students (versus educating all public school students).

The data driving these curriculums is proven to increase scores and graduation rates for Native American students, and those lucky enough to teach in these programs – I spent a semester teaching sixth, seventh, and eighth graders in Sioux Falls – credit this to the fact that Native students are able to relate to and buy into what they’re being taught.

This is big deal, given most American history classes relegate indigenous communities to that of a savage, inferior people, and contemporarily invisible.

I often reflect on the time in my AP US government class when a classmate raised her hand and asked why we had to learn about federal Indian policy if all the Indians were dead.

I kid you not! This girl – a senior in high school! – thought Natives were a race of the past – with me sitting right next to her!

Knowing she isn’t the only kid – or the last – to believe this makes these curricula that much more essential. It’s easy to treat someone as sub-human – say, with a racist mascot – if you think they don’t exist.

If you’re still wanting to teach and discuss Columbus, EDSITEment offers a wonderful lesson plan that can be utilized for a variety of classes and grades; the plan is based on actual journal or official document accounts of Columbus’ many journeys. The New York Times and teachinghistory.org offer great Columbus teaching resources, as well.

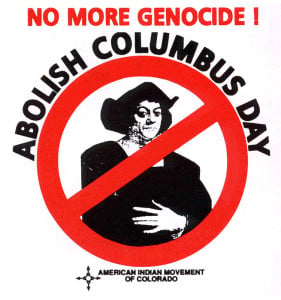

2. Support ‘Indigenous Peoples Day’ or ‘Native American Day’ Movements

For years – decades, really – there have been several small movements underfoot to throw Columbus Day overboard in favor of celebrations recognizing indigenous achievement and history.

Seattle is the latest in a steady procession of enlightened minds looking to downplay or replace Columbus Day with something that looks at actual history with an inclusive lens.

Earlier this year, the City of Minneapolis voted to celebrate Indigenous Peoples Day on the same day as Columbus Day. Around the same time this spring, Red Wing, Minnesota, voted to rename Columbus Day after its namesake, Chief Red Wing Day.

Meanwhile, California has long recognized a Native American Day (it was American Indian Day when it was first proclaimed in 1968) on the fourth Friday of September, but made it an official state, unpaid holiday in a vote this past June (the original legislation fought to replace Columbus Day, however).

And other cities in California – including Berkeley, Nevada City, Santa Cruz, and Sebastopol – officially recognize an Indigenous Peoples Day, which replaces Columbus Day in a couple of those municipalities.

While I live in Colorado, the state that first formally recognized Columbus Day back in 1905, my heart is in South Dakota, a state that’s been celebrating an official Native American Day over Columbus Day since 1990.

Although banks and other entities that get the day off continue to post “We’re Closed” signs referring to it as Columbus Day, and although Native/state relations continue to clash in often violent and harmful ways, I can’t tell you how proud it makes me to be from South Dakota on the second Monday in October. Like South Dakota, other states – including Nevada, Oregon, Hawaii, and Alaska – don’t recognize Columbus Day at all.

While some might bemoan the lack of oomph of some of these resolutions, the symbolic gestures to honor indigenous people are important to turning the tide of public opinion that Columbus is no one to honor.

Detractors of these movements often try to sell Columbus Day as one that celebrates Italian heritage versus hero worship of a monster. And while I have no problem celebrating the Italian heritage of others, I also know names are important. It’s called “Columbus Day,” and that’s the problem.

3. Use Columbus Day to Discuss Issues Relevant to Indian Country

Columbus encouraged human trafficking, rape, and child sexual abuse among his men. Authors David E. Stannard and Susan Kellogg (and others) use journal entries and official documents to detail what life was like for indigenous women post-Columbus:

“While I was in the boat I captured a very beautiful Carib woman, whom the said Lord Admiral gave to me, and with whom, having taken her into my cabin, she being naked according to their custom, I conceived desire to take pleasure. I wanted to put my desire into execution but she did not want it and treated me with her finger nails in such a manner that I wished I had never begun. But seeing that (to tell you the end of it all), I took a rope and thrashed her well, for which she raised such unheard of screams that you would not have believed your ears. Finally we came to an agreement in such manner that I can tell you that she seemed to have been brought up in a school of harlots.” (Journal entry of Michele de Cuneo, whom Columbus gifted the woman to.)

Here’s another entry from the explorer himself: “A hundred castellanoes are as easily obtained for a woman as for a farm, and it is very general and there are plenty of dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to ten are now in demand.”

This objectification of indigenous women has prevailed since the time of Columbus.

Today, we see hyper-sexualized images of Native culture on fashion runways, in Halloween shops, and pushed out by Hollywood.

The legacy of Columbus within tribal communities includes the highest rates of sexual assault and violence among any demographic. According to the US Department of Justice, one in three Native American women will raped in her lifetime; nearly half of all Native women will be beaten, stalked, or raped by an intimate partner; and our murder rates are ten times higher than the national average on some reservations.

And incidents of human trafficking increase significantly in the presence of oil fields and man camps and reservation border towns.

These numbers should scare you. They scare me.

My friends and colleagues who work with Native youth often describe teenage girls whose mothers instructed them on what to do when they’re raped. I repeat: The expectation among many Native girls is rape will happen. As a human being, I say that is simply unacceptable. And as a survivor of sexual assault, and as a mother to a beautiful Native child, I say the importance of this issue cannot be overstated.

It’s why I advocate for and support groups working to end violence, including those who fought to reauthorize the Violence Against Women’s Act, which has slowly rolled out new provisions giving tribal jurisdictions authority to prosecute non-Native sexual assault offenders (by some accounts, 88% of all perpetrators of violence against Native women are non-Native).

I get my information from a few highly active and forceful organizations working to end violence against indigenous women. The Save Wįyąbi Project uses social media to advocate for this important issue and has developed several community-based solutions – including teach-ins, event programming/education, and an interactive map for families and loved ones of missing and murdered indigenous women (#mmiw) – for Native women in tribal and urban areas.

Another great resource is the Native Youth Sexual Health Network, which works with indigenous peoples across the US and Canada to build comprehensive and culturally safe sexuality and reproductive health, rights, and justice initiatives in our own communities.

Organizations such as these do amazing work in tribal and urban communities, especially during October, fittingly slated as National Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

4. Stop Using the Term ‘Columbusing’

Okay, I admit, the College Humor video is funny. And the idea behind the term is funny, too: White folks think they discovered rock and roll, jazz, twerking, Harlem Shake, headdresses, and empanadas, among a vast host of other cultural goods.

Surprise! They didn’t!

And if we leave the idea of Columbus at the point where history credits him for “discovering” America, then “Columbusing” is an apt term. But if we’re being honest, then “Columbusing” isn’t calling you out for that chevron design print t-shirt from Urban Outfitters; it’s more that you’re trafficking nine-year old girls for sex and beating women with rope before you rape them.

Funny, right?

If you’ve learned anything from this article, it’s that acknowledging accurate history is crucial to moving forward from the issues plaguing marginalized communities. This would include recognizing Columbus and his impact as nothing short of monstrously evil, and definitely not something to be joked about.

***

I get it. Change is hard, and tradition is even harder to overcome.

But bad traditions – those that harm and work systemically to bring down whole groups of people – need to go.

Advocating for an end to Columbus Day not only disengages the education system from mythological history, but it increases awareness for and embracing of indigenous issues and cultures.

Holidays allow us to collectively approve history – at least the parts we’re okay with. These celebrations and honors turn into deep-seeded identities that form cultural beliefs, traditions, and heritage.

That’s why it’s so important to change how we celebrate the second Monday in October.

Because what we’re okay with now is a farce and harmful to indigenous people – women, in particular – who continue to be plagued by high rates of sexual assault, domestic abuse, and human trafficking.

For indigenous people, that’s what’s being “honored” on Columbus Day.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Taté Walker is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Mniconjou Lakota and an enrolled citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe of South Dakota. She is a freelance journalist who lives in the Colorado Springs area. She blogs at Righting Red and can be reached on www.jtatewalker.com.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32