Source: Anokhi Media

The recent Hindu-Muslim clashes resulting in arson in the Trilokpuri area of New Delhi have once again opened up discussions on the role of riots in Indian politics.

But for me, they opened up my memory box from the time when I visited a refugee camp a few miles away from New Delhi.

The camp took in survivors of the anti-Muslim riots in the Muzzafarnagar district of Uttar Pradesh in northern India last August.

As I walked past the helpless crowd of women and children on the first floor of the Madrassa-turned-refugee camp, I remember observing a thin old Muslim woman. A man, carrying some packets of cookies, entered the dimly lit room, and the old woman’s eyes lit up in anticipation. Then filled up with tears. She didn’t get the cookies.

Angry, struggling, and helpless over a packet of cookies. This is what the anti-Muslim riots in her village had done to her.

I found out that the people who burned her house and her cattle were people she already knew. They were people she saw on a daily basis – popular and familiar faces in her village, neighbors, and even casual friends of her grandsons.

So, how does acquaintanceship end up creating such hell? How do people find it in themselves to be oppressive and violent towards a group of people because of their religious identity?

I want to point out here that minority oppression isn’t just about anti-minority violence. It is also about how we assert our prejudice in a way that maintains the possibility and feasibility of violence. It is about the subtle ways in which we knowingly or unknowingly manifest our prejudice.

We take in prejudice slowly and silently through socialization. Nobody is born prejudiced against one group. It is socialization which makes us part of the systematic oppression of certain groups of people.

But because we learn prejudice, we can also unlearn it. Liberating our minds is a worthwhile effort and is our own responsibility.

When we as individuals begin to fight oppression in the everyday lives of other people, we add to our collective strength of dissolving the hatred that creates hells such as the Muzzafarnagar communal riots.

Here are a few ways you can fight oppression and practice political consciousness and communal harmony in your everyday life.

1. Introduce Your Friends to Each Other

In 11th grade, my best friend told me that in order to stay “safe” in online chat rooms, she avoided chatting with anybody with a Muslim-sounding name.

I was shocked. How could she say something so blatantly Islamophobic? Was my friend contributing to the growing Islamophobia around the world?

She must not have known it then, but what seemed like a “safety mechanism” to her mind is actually oppression. It ranges from avoiding talking with Muslims to refusing renting houses to them, from calling a classmate or colleague a terrorist because of their Muslim identity to anti-Muslim violence in areas with Muslim minorities.

Like so many of us, my friend had learned from somebody that following a certain way of thinking was the best way to keep the society and herself “safe.” We take in these messages by observing and learning things about our society, and soon we start to replicate them.

Society labels certain people as the “other,” and once this message becomes part of our belief system, we don’t want to see, hear, or know the “other.”

As is basic human psychosociology, we connect with people by finding out if we’re similar or not. And in the 11th grade, my friend didn’t think she had anything in common with anybody who had a Muslim-sounding name. They were “other.”

A few years later, I introduced her to a very good friend of mine who is a Muslim. I feared she would come with whole lot presumptions. But after sharing a nice lunch and laughing over the same jokes, she told me, “He’s so interesting and funny!”

That was a big shift in her attitude.

Sure, that afternoon may not have undone all forms of prejudice. But humanizing the people from other communities goes a long way in eradicating the idea that they are inherently different, and therefore threatening.

So, throw a lunch or dinner party and invite your friends from all religious and cultural backgrounds. Share the story of how you met them.

You don’t necessarily have to make their religion a part of your dining table conversations, but their interests, talents, and quirks will go a long way in building new friendships among them. You’ll be setting a very good example of communal harmony right in your dining room.

2. Acknowledge Your Privilege

These days, it’s not uncommon in India to hear upper caste Hindus complain about “Muslim appeasement” and about how they are treated as “second class citizens” now that people from the marginalized classes get reservations in government educational institutions as part of affirmative action.

These complaints are not only factually inaccurate, but they’re also extremely insensitive towards those who actually are discriminated against.

In India religious minorities (and especially Muslims) face severe security issues. The domination of “Hindutva” in public discourses in India has subtle anti-minority, especially anti-Muslim, undertones to it. The attempt at “saffronization” of Indian society, simply put, is an attempt to define India as a Hindu nation, thus blatantly omitting the diverse cultures and communities.

To understand oppression in other people’s lives, it is important to recognize ways in which we aren’t oppressed—something the upper caste Hindus have failed to do. Even as a non-religious person, I know that I am privileged because others see me as part of the Hindu majority in the country where I live.

Being seen by others to be part of certain groups “protects” us in ways that we often fail to recognize. Our religious identity plays a terribly crucial role in whether or not we will be held under suspicion in case of a terrorist attack, for example.

Whether you are a practicing or a non-practicing Hindu/Muslim/Christian, as long as you are viewed as part of the majority in your country, you benefit from that position. You don’t have to feel bad about it (in fact, privilege guilt is extremely counterproductive), but you have to recognize that political, social, and economic structures are biased towards you regardless.

People often wonder if they’re obliged to use their position to talk about the things that others who aren’t privileged cannot talk about. I don’t think it’s an obligation — but I do think it’s an opportunity that’s too important to miss.

So, acknowledge and accept that you are privileged. And help your family and friends recognize their privileges by talking about them.

3. Be Open to Surprises

I did my post-graduation study in a Muslim university, which sparked the curiosity of my Hindu acquaintances: But isn’t that only for Muslims? Do you have to dress conservatively? Do they make you read the Quran?

My answers were always no, no, and no with a straight face. And my acquaintances would seem almost disappointed. My answers didn’t match their idea of what a space with a Muslim majority would look like.

It is always uncomfortable to unlearn things about the world. But it is often by unlearning that we find out more about the world because we let things simply be instead of molding them into how we’ve learned they should be.

Often when we meet somebody who belongs to a different religious background, we expect them to be extremely religious and conservative, or to embody the stereotypical depiction of that religion. And since we usually don’t make an effort to get to know them any better (see #1), we don’t question this expectation — we just accept it as true.

But they might be agnostic or atheistic. Maybe they’re as religious or non-religious as we are. Every religion is made up of diverse, complex people — so we shouldn’t be surprised when we see that complexity in individuals!

Surprises can be uncomfortable, but they change something in us. And when a steady dripping of close-minded attitude keeps trying to rust away at our belief systems, change can be a very good thing.

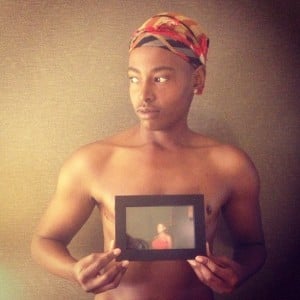

4. Don’t Judge Others by Their Clothing

We live in a world that is so obsessed with information that we use shortcuts to grasp it. We scan the newspaper headlines while drinking our morning coffee. We put a 140-character limit on our thoughts and updates. We rapidly click on hyperlinks in online articles, never bothering to finish what we set out to read in the first place.

We love shortcuts to information.

And it’s a lot of work to spend time getting to know the complexities of people from such a wide range of cultural backgrounds. So oftentimes, we take a shortcut. We judge them by their clothing.

But that’s not knowing them.

To assume people’s personalities and life situations based on the stereotypes associated with their clothing is not only a narrow-minded outlook, but is also dehumanizing and disrespectful towards those people.

It’s difficult not to fall for stereotypes, but treating people according to a mental image is actually failing to recognize them as individuals with an identity of their own. When we fail to do this, we turn them into an “ideal” victim or oppressor. We turn righteous and feel compelled to be concerned.

In this process, we feel as if we are more modern, more scientific, more civilized, more sensible, and otherwise superior to the people we judge.

When we give into the temptation of judging people based on their clothing, we miss out on connecting with their complex mind and multi-layer personality; we miss out on connecting with another human being.

Sometimes it’s difficult to accept that a headscarf does not define a person’s thought process, but the reality is that it doesn’t. So the next time you meet a person wearing one, ask them a question or listen to the joke they’re telling, instead of listening to the clothing they’re wearing.

5. Talk about Religious Discrimination and Minority Oppression

During my aforementioned visit to the refugee camp, I heard haunting stories of women whose breasts were chopped off, women who were gang-raped, old people and children who were mutilated, and men who were brutally killed.

These are not my favorite stories; they can’t be. But I told these stories to my friends because I believed they should know what was happening in a village few miles away from where they lived.

If we aim to build a community that has a strong sense of moral certainty on human rights issues, then it is important to express condemnation and to show defiance. For most people, getting the word out comes from a deep sense of responsibility towards the global community.

No, talking about it won’t directly change the situation or remove the problem, but it is always the first step toward change in any course of action.

If you can, talk about oppression.

***

Political consciousness and communal harmony can blend together very well.

And if you’re able to create this blend, create a space in your life where individuals from all religious and cultural backgrounds can enter — talk, laugh, and eat together — then you can start to shift the world away from fear and hate.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

R. Nithya is a Contributing Writers for Everyday Feminism. She lives in New Delhi, India and has a Bachelor’s in Journalism and a Master’s in Political Science and has worked as a reporter with an online political news and analysis magazine. She enjoys reading books while traveling on the metro, writing poetry on sleepless nights, and engaging in conversations on politics, feminism, and spirituality. These days she is practicing patience and presence. Visit her here or follow her on Twitter @rnithya26.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more