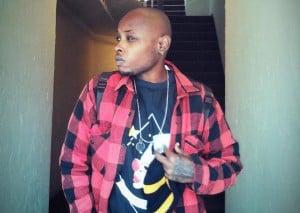

This poem has two working titles. It might end up having five working titles. The first one is “Privilege Is Never Having to Think About It.” And the second one is “Touring with a Black Poet: For Sonya Renee.”

She steps out of the hotel bathroom dressed to the nines — stilettos sharp in her glossy, glossy, elegant, tailored, boom glittering, a bold burgundy neckline — locks her shining eyes in the worn t-shirt I haven’t changed in days and says, “Are you going to wear that on stage?”

I smile, gloating in the cool of my gritty apathy, the oh-so-thrift-store of my dirty grunge. She says, “honey, do you have any idea how much privilege it takes to think it is cool to dress poor? You wear that dirty shirt; you are a radical saving the world. I wear that dirty shirt, and I am a broke junkie thief getting followed around every store.”

That conversation happened years ago. On the same tour where Sonya watched me pay 75 bucks to have my hair cut in a way that would make me look like — quote — like “I couldn’t afford a haircut.”

The same tour that began the day after I was the feature performer at a university’s women of color symposium. No, I did not ask whether or not featuring a woman of color instead. Yes, I got paid. I’m pretty sure it was a good paycheck.

Just like I’m pretty sure someone licked the paycheck when Trayvon Martin’s gun range targets got sold out in two days.

I know those things are not exactly the same

I know I wanted to burn every noose white seam of our cotton flag when Trayvon Martin’s mother was on the witness stand trying to convince a jury of mostly white mothers that she could actually recognize the sound of her own son’s scream.

I know I wanted to split the fucking sky when I heard the whip of the verdict and Sonya had posted online, “How many different ways can this country tell me I am worthless?”

I know it was right then that I walked upstairs and started counting the hoodies in my closet. I have fourteen hoodies that tell me I will never be forced to dress a wound as deep as my mother’s heart. She will never be woken in her sleep to peel my body off gated grass, to beg God to sow the hole in my chest.

I know my family will never have to hear justice, say it wasn’t until I was lying in my casket that I was wearing the right clothes.

I know a woman who once knew a woman who collected the metal collars they used to lock around the necks of black children to chain them to the auction block. I was told she hung them on the walls of her home for decoration. I remember when I used to believe that was the entire definition of racism.

Believed there was no one hanging in my wardrobe. Believed my style had nothing in common with king Leopold’s. Thought I am not outfitting the Congo in spilled blood.

I am just buttoning up my shirt here. I am just rolling up my sleeves. I am not unstitching the face of Emmett Till. I am not unzippering the wail of his mother’s grief.

The laces of my shoes are just the laces of my shoes. They could not tie a body to a tree. I am not fashioning a noose here.

Sonya, do you hear me?

My compassion is not a costume. My passivity is not hate. My privilege is not genocide. This is just how I cut my hair. That was just how they cut the check. This is just how I dress.

Your wound.

I don’t even think about what I wear.