Source: Try This at Home, OK

I’ve always been suspicious of a feminist politic that I can’t communicate to my family, especially my mother.

Lately, as a recent college graduate entering the “real world,” I have wanted to write about the struggle of coming home to find yourself and your values seemingly at odds with your own family.

As a student in college, I would often immerse myself in feminist theory and politics at school and come home and be unable to communicate the ideas provided and lessons learned to my mother. And there is something very unsettling about preaching and aspiring to politics of liberation that alienate your own mother.

It’s even more confusing when you know implicitly that your mother is the embodiment of a feminist praxis you aspire to, even if that’s not what she’d necessarily call it. I sometimes felt like I was talking down to my mom, using a language she was unfamiliar with, disconnecting her from these important ideas, and therefore disconnecting us.

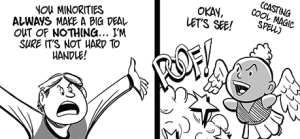

So I wanted to write something for those of us that feel that struggle with the same – that twinge of discomfort when their parents say something racist; those of us who refuse to cast off their parents as “backwards,” but also can’t communicate effectively with their families on the issue of justice; those of us who got the theories from gender studies classes in college, but will always return to the home for a working definition of feminism.

Because it’s hard.

So here are three ways to reconcile your theory and your at-home praxis:

1. Engage with Your Mother

That’s right. Especially when you don’t want to.

This might require some decolonizing of your communication skills—that is, picking up on how a family member articulates their politics through their words and actions in a way that isn’t recognizable to some of us who have yet to wean ourselves off of Western academic jargon.

When I took my first feminist theory classes, it was liberating for me to have a language to describe my experience as a woman of color in a white supremacist world. This is the experience of many of us who were politicized within the walls of the classroom.

However, we often forget that knowledge doesn’t come from textbooks – it comes from the streets. It comes from people’s lived experience and histories. The violence of the academic world is that it makes us forget that.

So, one holiday weekend, I told myself that I would refrain from correcting the views that my family expressed that were offensive to me, and I found myself surprised by what they had to say.

When I engaged genuinely, rather than just to jump in with a counterpoint, I deeply appreciated the way that radical values were peppered through their dinner prep banter.

Over glasses of wine, my mom and her sisters would wrap momo dumplings as they talked about their lives and shared homemade remedies.

Suddenly, when I heard my mom complaining about her job, I realized how much it echoed what I, in other spaces, might call a sharp critique of the nonprofit industrial complex. Her homegrown remedies and beauty tips from her kitchen cabinet were direct interventions into the corporatized medicine industry.

I was humbled and reminded of what Audre Lorde said in her speech “Learning from the 60s”: “When I hear the deepest truths I speak coming out of my mouth sounding like my mother’s, even remembering how I fought against her, I have to reassess both our relationship as well as the sources of my knowing.”

A huge part of communication is being aware of context.

For me, context means understanding my family’s stories as migrants, specifically migrants who were privileged enough to migrate, but not enough to totally assimilate, which is a very important nuance.

Knowing my family’s story helps me understand where they’re coming from in a way that makes me feel less prone to feeling triggered when they say something prejudiced.

I have found that I can enter into conversations with them much more productively when I am aware of their context. With context in mind, I am fixating less on the language they are using, and more on what they are trying to communicate to me.

For example, when I understand my parents’ story as first generation migrants to this country who struggled to start a new life with little money, I can be more compassionate about their concerns that my career choices aren’t as financially ambitious as they might have hoped.

Their disappointment doesn’t feel as harsh when I understand that though it’s projected onto me, it’s larger than me: It is a hauntingly sad, but justified disappointment with the “American Dream.” There were hopes they had banked on and a fantasy of class ascendency.

I can be sad about that, too, sad about the trick they fell for – capitalism disappoints in many layered and complex ways.

2. Develop Your Own Language

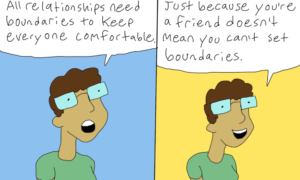

When you’re engaging carefully enough, you’ll find that you’re usually not using the same language as your family in conversations about social justice.

I found that the gap in communication was tied to other differences between my family and me, including home countries, mother tongues, and generations. I realized that it was crucial to build — not find — common ground.

I was not interested in a language of liberation that would take me farther from my home, but I also was not willing to accept that my family’s politics would never change.

I wanted a new language — one that was homegrown and not imposed or transplanted.

I didn’t want to use the words “oppression” and “systematic” when, because they come off as, to my mother, like a part of the academic world she didn’t belong to, they had the effect of shutting down conversation.

It’s hard to describe what it means to develop your own language when discussing social justice, but it often means letting go of language as we know it altogether. It means finding meaning in our everyday actions and gestures and seeking understanding from there.

Today, I try to find opportunities to ask my mom about her life before she came to this country. In my head, I translate what she says to the language I know.

Suddenly “not enough money” turns into insight about how capitalism creates conditions of vulnerability and insecurity for migrants. “Don’t speak up, just do your work” can be her wish for the safety (and illusion) of assimilation for her family in a country reigned by white supremacy. There was always something to unpack.

Communication is reciprocal, and I found that when I paid attention to my family, they would usually pay attention to me. Paying attention to them gave me the tools to discuss social justice with them in the language they knew.

Developing a common language is tricky, very personal, and specific to individual circumstances.

One thing I’ve found is that a shared language can be built on shared experiences.

This can be as simple as sharing a book or movie that has inspired you with your family members. I developed a list of films and texts that I thought my mom and I could both relate to, and eventually we found ourselves watching and bonding over Joy Luck Club and The Namesake.

Our lives were so different and vast that it sometimes seemed incredible that we could find overlapping understanding in the few hours it takes to watch a film.

But that connection is so important.

I recently talked to a friend about how we felt like our mothers had “radicalized with us.” And it was comforting for me to know that we could have a feminist politic that didn’t alienate our family, which instead brought them along with us on our own journeys.

3. Question What You’ve Learned

The most important change I had to consider about engaging intergenerationally with my family in discussions around social justice was questioning my own knowledge.

Going back to Audre Lorde’s quote, I found myself reassessing “the sources of my knowing.”

What did I know about oppression if I read about it in a classroom? Why was what I saw as a “revolutionary education” distancing me from my family? I realized that there was no point in knowing the language of social justice if I couldn’t communicate with it to those closest to me.

The ways I had previously engaged with my family in these discussions was presumptuous of their ignorance. Such a presumption of ignorance and backwardness is linked to the legacy of colonialism, which sees “the West” (or in this context, the United States) as the ultimate standard of progressiveness.

Presuming ignorance as the cause of misunderstanding and miscommunication is a form of that colonial thinking that attributes backwardness to the lands our parents’ came from.

That presumption leaves no room for the idea that we are perhaps more “ignorant” than our parents, or that “ignorance” is a reductive of thinking about difference and a violent way to erase histories.

***

I have learned that bringing conversations about social justice into my home is an ongoing process.

It’s easy to give up, compartmentalize, and see social justice work as something separate from your home and community. But to do so would be to turn your back on collective liberation from systems of oppression.

And it is crucial to involve our families in our revolution.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Rebecca John is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a thinker who recently graduated from university. Freshly out of the academy, she is happily rejecting the academic industrial complex and spending her time immersed in movements for social justice. She enjoys frequenting bakeries, recommending readings to her friends, and long meditative subway rides. Follow her on Twitter @r0guebird. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more