Source: All Booked Up

Despite the many times that the age-old argument has been turned on its head, the suggestion that “the oppressed cannot oppress” is still very much around.

When I was a first-year student at a predominantly white college, I grew frustrated by my peers’ constant denial that racism was alive and well. As a queer, Black, and gender variant student leader on campus, I became very active in creating spaces for LGBTQIA+ students and students of color.

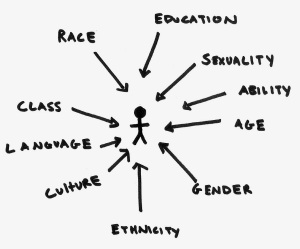

At this stage of my life, I had a firm grasp and understanding about how I was a minority in multiple spaces. But I had given little consideration to the many ways that I also held power.

How did my light skin affect my experiences of racism and grant me safety in certain contexts? Were the cultural events I was facilitating wheelchair accessible? Did they offer sign language interpretation? How had I been set up to succeed in college as the child of parents with advanced degrees?

By focusing only on my minority status, I remained unaware of issues impacting others, and, at worst, unconsciously participated in furthering oppression.

I eventually realized that my role in anti-oppression meant not only talking about my hardships, but also constant reflection on and re-assessing of (as well as—yes—fucking of up because of) my privilege.

If I was to claim that I was committed to making spaces safer and liberation for everyone, I had to take a closer look at myself, my privilege, and my assumptions.

Challenges in Recognizing Privilege (And Why It’s Still Important)

At first, I was somewhat resistant to the idea of “unpacking my privilege.”

Even though I understood privilege as a concept, I understood it more as some that harmed me rather than something I also benefited from. When bogged down by the toxicity of racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, fatphobia, transphobia, and so on, it can be hard to conceive that we are privileged at all.

Our status as marginalized remains in the forefront of our attention, because we feel most impacted by it on a daily basis.

There is true value in this—in being brave enough to raise our voices, speak out in the face of discrimination, and build community around shared struggle.

And, if we remain solely focused on our marginalization (or consider ourselves incapable of oppressing others), we may have a more harmful impact than we ever intended: We may respond to being oppressed with more oppression.

We may not know that we’re doing something fucked up and become defensive as soon as we’re challenged. We may deflect to our minority identities to dodge accountability when we are being oppressive: “I’m _______, so I’m not ________.”

These common responses are super problematic and challenging, and can create further separation.

So, here are a few things to consider when struggling to accept your privilege as a marginalized person.

1. Be As Committed to Learning About Your Privilege as You Are Your Marginalization

I am a Black, queer, genderqueer young person struggling with anxiety and depression.

I am also an English-speaking US citizen, have a roof over my head, have access to health and psychological care, am temporarily able-bodied, middle-class, light-skinned, thin, college educated, and was raised in a supportive family environment. (Coming up with that second list was like finding a needle in a haystack—and I probably missed several!)

The tricky thing about our privilege is that we often don’t even know we have it. And once we do know, it can be hard to understand how it manifests in our lives.

If you’re a working-class white woman, consider still how you have benefited from institutionalized racism and white privilege. If you are a queer man of color, check your sexist assumptions. Oppressive socialization impacts us all—whether we have one or more minority identity or not.

Delve into history or knowledge about an identity you don’t hold. Be committed to understanding your privilege in a variety of contexts—at home, in the office, in the bedroom, everywhere.

Power and privilege exist in many capacities, and the more we recognize it (or it is brought to our attention), the better equipped we are to be more aware in the future.

It isn’t easy or straightforward, but owning all of who we are in our complexities can lead to deepened empathy and capacity to build authentic relationships across difference.

2. Recognize That Oppression within Oppressed Groups Does Exist

As a college student attending the National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education (NCORE), I attended an African American caucus group. When it came my time to share, I talked about my struggles with Black identity—about my conflicting experiences as a “fair” (meaning light-skinned) person.

Afterwards, I was approached by an older woman with a deeper complexion who challenged my use of the word “fair.” In her generation, this term suggested superiority—if lighter skinned people are “fair,” what does that mean for folks of darker shades? What do we call them?

Although I had given some thought to my privilege in this area already, I was stunned and even ashamed. This conversation served as an emotional reminder to me that – although I share ancestry and similar history—I remain privileged regardless.

Our sharing of a common or umbrella identity (my being African American, for example) does not erase the power we may still have within that group.

Try and pay attention to how your identities (dominant or marginalized) can shift depending on context.

For example, while my masculine-presenting gender is often target of harassment and violence in mainstream US culture, it also grants me privilege in many queer and femme spaces.

Understand also that there will be times when marginalized folk seek to connect with each other, and each other only. Asking for “allies to stay home” can cause confusion for those who are sympathetic to a cause or group—“but we’re in solidarity with you!”

These identity-specific spaces are usually responded to with anger, outrage, and entitlement, but they are about survival.

Be aware of the fact that there are experiences you may not share with others and vice versa, despite relating to their identity in other ways.

3. Listen, Validate, and Then Relate

When we come together looking for support around the latest fucked up thing we’ve been through, we rightfully want our experiences to be validated. We want others to understand where we’re coming from, to share our hurt.

At the same time, the last response I want to encounter when discussing my most recent interaction with racism is something to the effect of “I’m gay, so I understand the struggle, sister!” from a white, gay, upper-class cis man.

Rather than immediately relating what someone has shared to your own experience, express empathy and concern and ask if and how the person needs further support.

Seek the middle ground between understanding your oppression in relation to someone else’s and invalidating what they’ve been vulnerable enough to share.

4. Be Patient with Yourself and Others

None of these considerations are easy, especially when we are already dealing with the daily slings and arrows of oppression. I’m all too familiar with the feeling of being called out on my privilege, and long after I had considered myself to be an activist.

Whenever I recognize (or am told) how my privilege has caused me to overlook, oppress, or display a sense of entitlement, a million thoughts race through my head, mainly: “How could I have done this? I’m oppressed, too—I should know better by now!”

The emotions of guilt and self-doubt that perpetuating oppression creates don’t feel good, but I’ve come to accept them as part of my learning (and unlearning) process. I have had to learn to forgive myself again and again—and to work toward doing better in the future.

Continue remaining true to yourself in all of this. Recognizing your power doesn’t suddenly erase the challenges you face just in being who you are, just as your oppression doesn’t mean that you have no privilege.

Practice forgiving yourself for mistakes while still accepting responsibility for the impact you may have.

5. Remember What There Is to Gain

As people, we are each complex in our identities, beliefs, practices, and values. And our understanding of ourselves—all of ourselves—greatly influences how we engage in ending oppression of all kinds.

The process of examining our power—and even choosing to give some of it up—is emotionally taxing, even more so when we cannot comprehend “what’s in it for us.”

The fact of the matter is, there are many benefits to the process, even as people with various oppressed identities.

Taking a look at our privilege can lead to better self-understanding, expanding our view from simply what happens to us (as victims of oppression).

But once we have a better grasp on how our power can be harmful to others, we can interrupt those behaviors and build stronger coalitions. We can reframe privilege as something that we have, but that we can also use for change.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more