A blindfolded person in a suit reaching their arms out. Source: Midwest District Blog

Author’s Notes: While this article argues that colorblindness as a concept is problematic, I’d also like to acknowledge that colorblindness as a term is problematic, as it could easily be considered an example of ableist language. In the end, I chose to use the term, but I hope that in ridding ourselves of the concept, we can also rid ourselves of the term.

Thank you to my former students who have shared their race-based experiences, enabling me to write this article.

You’ve heard it said before. You might have been the one to say it.

“I don’t see color. I just see people.”

Or maybe: “We are all just people.”

Or it might have been “…” – the sound of silence.

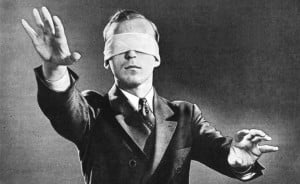

Such comments (and racial avoidance) have a name: colorblindness.

The colorblind approach to race is not an accidental phenomenon; rather, it is the result of an education – a training – that many of us have received, especially White Americans.

Many of us are taught from an early age that talking about race – even just acknowledging race – is a no-no.

In some ways, colorblindness makes sense: Race can be uncomfortable – its mere mention can thicken the air with tension.

Moreover, this country’s racist history is deeply uncomfortable: “Let’s just start fresh in a world where we don’t acknowledge racial differences and, with luck, we can move beyond our racist past. After all, this country is a big melting pot anyway.”

Unfortunately, like many other lessons we have been taught – drinking juice is good for you, complimenting appearances is always nice, menstruation is gross and shameful, asking Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders where they are really from is okay – colorblind ideology is fraught with problems and pitfalls.

Before I elaborate, please don’t feel judged if you have espoused such an approach in the past.

As I mentioned, how could many of us not do so after years of training?

I have spent nearly 15 years in public high school classrooms, and my students – particularly my students of color – have provided a wealth of evidence that, when it comes to colorblindness, we desperately require an alternate training.

Since it’s the responsibility of White folks to educate ourselves and each other (and not expect people of color to be our trainers), I encourage you take to heart the seven reasons I’ve already been taught:

1. Colorblindness Invalidates People’s Identities

Because of the prevalence and history of racism, just the word “race” can conjure negative connotations.

However, racial oppression (not to mention the flipside, racial advantage and privilege) is just one dimension of race.

Race is also intimately tied to people’s identities and signifies culture, tradition, language, and heritage – genuine sources of pride (and not in the White Pride kind of way).

Like many other factors – gender, religion, socio-economic status – race is a basic ingredient that makes up our being, whether or not you consciously acknowledge its role in your life.

Imagine being forced to suppress one such ingredient that you openly acknowledge and value. Imagine, for example, being forced to let go of your religion. For people whose faith is a fundamental part of their lives, such a thought is unfathomable.

Yet doing so for race makes no more sense.

Asked what he appreciates about his race, one student – who describes himself as Japanese, Black, and English – responded, “My race is everything to me.”

For this student, not to mention many others for whom race is a valued part of identity, what would colorblindness leave him with?

Denying people their identities is not racial progress, but rather harkens back to this country’s sordid racist history. Slavery depended on severing the cultural ties of stolen people. The Indian Boarding School movement had similarly devastating effects on Indigenous groups.

True progress will come when White Americans no longer feel threatened by the racial identities of groups of color.

2. Colorblindness Invalidates Racist Experiences

Colorblind ideology takes race off the table. But for many people of color – as well as for White people who work to dismantle systems of privilege – race is very much on the table. Racism forces it to the tabletop.

Colorblindness just pretends the table is empty.

I’ve worked with a Mexican American student who overheard a White American student say, “I hate Mexicans.” I’ve worked with an African American student who endured being called the N-word by a classmate and another Black student mistaken for a drug dealer.

Students of color at the predominately White school in which I work have described themselves as “bad seeds” and “outcasts.”

Who benefits when those stories are suppressed?

Most certainly not these students of color, who must swallow their stories and bury their experiences. Beverly Daniel Tatum, author and president of Spelman College, explains that the cost of such silence on students of color is isolation, “self-blame,” and “self-doubt of internalized oppression.”

Instead, we need an environment where such stories are heard, valued, and then thoroughly addressed.

Unfortunately, colorblindness derails the process of addressing racism before it has even started.

3. Colorblindness Narrows White Americans’ Understanding of the World and Leads to Disconnection

White Americans are not the only ones who adopt a colorblind approach to race but, in my experience, they are far more likely to than any other racial group. Ultimately, however, colorblindness hurts them as well.

I explore this topic in much more depth in a previous article. In it, I argue that White Americans who avoid race, a behavior that colorblindness encourages, have a skewed view of the world.

After all, understanding any situation requires multiple points of view. A news story must consider various sides of any conflict to keep itself out of the editorial section.

A court trial could never be considered fair if only the prosecution presented its case. A novel could never be fully understood if we only read about some of the characters.

Novelist, and perhaps coolest-person-ever, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls for multiple perspectives so that we avoid what she calls, “the danger of the single story.”

Colorblind ideology limits the stories that get told, keeping White America comfortable, but also keeping racism thriving.

It also causes disconnect. If you are espousing colorblindness, your failure to deeply understand race means you have likely been tripping down a long unnecessary road paved with stereotypes and microaggressions.

And while you may have been banking on the bliss that comes with ignorance, the people who know full well that race really fucking matters — people of all colors — do not trust you.

The result: Colorblindness cuts you off from so much beauty in this world.

4. Colorblindness Equates Color with Something Negative

The comment “I don’t see color; I just see people” carries with it one huge implication: It implies that color is a problem, arguably synonymous with “I can see who you are despite your race.”

As evidence, note that the phrase is virtually never applied to White people.

In over 40 years of life and nearly 15 years as an anti-racist educator, I have yet to hear a White person say in reference to another White person, “I don’t see your color; I just see you.”

In my experience, it is always applied to people of color (nearly always by White people).

For the students of color whose race is core to their identities, the comment effectively causes many to feel “invisible.”

“Then you don’t see me,” one student of color once responded.

Multiracial students who look very White have shared stories of having their faces examined, often by White people, looking for “what else” is in there. The whole scenario assumes white is the norm and the something “else,” the color, is not.

Altering the scenarios often serves to illuminate the flaws in such comments. For example, I once said to my Jewish wife, “I don’t see your Jewishness; I just see you.” Until I explained my intentions, the experiment did not help our marriage.

5. Colorblindness Hinders Tracking Racial Disparities

Racial labels and terms are complex, evolving, sometimes limiting, and often problematic. But the problems associated with the colorblindness are arguably far worse. Without being color conscious, we would never know:

- Black preschoolers are three times more likely to be suspended than White students. Preschoolers. This data from a federal study has prompted some to rename the school-to-prison pipeline the preschool-to-prison pipeline.

- In Seattle, despite making up just a tiny fraction of the district population, Native American students had a “push-out” rate (more commonly known as “drop-out” rate) of 42% during the 2011-2012 school year.

- In the school district in which I work, Seattle Public Schools, Black middle school students are nearly four times more likely to suspended than White students, a disparity that prompted a federal investigation by the Department of Education. (See graph below.)

Unfortunately, deep racial disparities are not limited to education.

If a person’s race truly shouldn’t matter – which I acknowledge most people are trying to communicate when they espouse colorblindness – then such disparities wouldn’t exist.

With such staggering disparities, again I ask: Who benefits when we ignore such racial categories? Certainly not those most negatively affected.

6. Colorblindness Is Disingenuous

If you are saying “I don’t see color; I just people,” I’m sorry, but I just don’t believe you.

Essentially, you are saying that that you don’t notice any difference between Lupita Nyong’o and, say, Anne Hathaway, two similarly aged actresses who I’m betting have never been confused for each other. They are both just people, exactly the same.

Really? Again, I just don’t believe you. And Idris Elba playing James Bond won’t ruffle any feathers, right? (Just like no one noticed when he played a Norse god in Thor.)

Was it really just openly racist people who objected to these casting choices or were they joined by proponents of colorblindness?

Or when you see a group of Black youth walking toward you on the sidewalk, you feel the exact same feeling as when it’s group of White youth?

Though the concept of race is a social construct and ever changing, let’s just be honest that those of us who can see really do see the physical differences (skin, hair, eye shape) commonly associated with what we call “race.” If you are choosing colorblindness to avoid being racist, you have chosen the wrong strategy.

7. Colorblind Ideology Is a Form of Racism

In fact, just a few years ago, Psychology Today published an article titled “Colorblind Ideology Is a Form of Racism.” See?

Colorblindness is far more of a threat to racial justice than White Supremacists (who seem to be quite color conscious). After all, if you can’t discuss a problem, how can you ever solve it?

As Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun famously wrote, “To overcome racism, one must first take race into account.”

But if you don’t believe Blackmun, just ask PBS, arguably the least controversial resource a teacher can ever hope to use in the classroom. On the website of the PBS series, The Power of an Illusion, it is written in no uncertain terms: “Colorblindness will not end racism.”

***

In the aftermath of high profile cases of racist police practices, scores of articles have been published providing White Americans with advice on how to address racism. Here are a few:

- “7 Ways to Demand Change If You’re Feeling Hopeless and Helpless After Ferguson Decision” from Huffington Post.

- “12 Ways to Be a White Ally to Black People” from The Root

- “12 Things White People Can Actually Do After the Ferguson Decision” from Huffington Post

- “On Ferguson and 4 Ways We can Choose to Divest from White Supremacy” from Everyday Feminism

- “What white people need to know, and do, after Ferguson” from The Washington Post

If you add those up, you’ll end up with a lengthy list of ideas. Not one argues for colorblind ideology.

As investment firm president Mellody Hobson says, let’s be “color brave,” not colorblind. Without such bravery, Selma director Ava DuVernay confirms, “You’re missing out on a lot of beautiful colors.”

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Jon Greenberg is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is an award-winning public high school teacher in Seattle who has gained broader recognition for standing up for racial dialogue in the classroom — with widespread support from community — while a school district attempted to stifle it. To learn more about Jon Greenberg and the Race Curriculum Controversy, visit his website, citizenshipandsocialjustice.com. You can also follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more