Source: The Austin Diagnostic Clinic

(Trigger Warning: Sexual abuse, sexually inappropriate behavior.)

One of the most controversial news stories in 2014 was the release of Lena Dunham’s memoir Not That Kind of Girl – and in particular, the chapters of the book in which Dunham recounts her childhood relationship with her younger sister, Grace.

Much of the criticism of the book surrounds several passages where Dunham describes bribing her sister for kisses, masturbating next to her in bed, opening her sister’s vagina while she is playing in the driveway, and doing, in Dunham’s words, “[b]asically anything a sexual predator might do to woo a small suburban girl.”

Many critics of Dunham allege that these acts were indicative of sexual abuse on Dunham’s part. Dunham, in her response to these allegations, quite vehemently denies that these acts were sexually abusive. She posits that these behaviors are within the scope of normal child-like behaviors, and that she, in no way, considers herself to be an abuser.

There has been a substantial amount of literature written (including here on Everyday Feminism) about whether or not Dunham’s actions constitute sexual abuse, both from her supporters and her detractors.

Regardless, one issue that has been brought to the forefront due to the media focus on Not That Kind of Girl is how we teach children to give, receive, and understand “consent.”

Whether or not you regard Dunham’s actions as sexually abusive, the fact remains that in none of the instances described did her younger sister consent to Dunham’s actions. More importantly, it is unclear whether or not Dunham — as a child — understood the nuances of consent.

Why Kids Should Start Learning About Consent ASAP

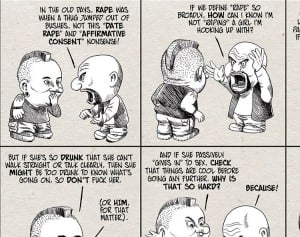

The way consent has been framed for most children — in cases where it is explicitly addressed — is that we tell kids something along the lines of “If someone says ‘no,’ then you need to listen to them.”

While this is an important lesson, it is normally as far as the discussion goes.

And simply couching all aspects of consent into this one no-means-no phrasing misses several key components of consent that are essential for kids to learn and employ as they start developing interpersonal relationships.

Discussing consent with a child in only this way proposes that “no” is the only form of non-consent available. This isn’t true, and when children learn about consent in this way, they can grow up with a sense of ambiguity about what constitutes consent.

Because discussing all aspects that encompass boundaries and consent can seem incredibly overwhelming – especially when trying to explain them to a child – many adults shy away from talking to kids about consent in a way that is comprehensive.

However, discussing consent with children in a way that acknowledges its various facets is hugely important because as children go through adolescence and then adulthood, the way that they have learned about consent as a child will inform how they interact with other adults and children in their own interpersonal relationships.

How to Teach Consent

Teaching consent to children can be done in a variety of ways, and teaching consent doesn’t always have to be in the form of a long sit-down discussion about consent (although those discussions are important, too).

In fact, teaching consent is an ongoing process in which different scenarios come up as children grown and learn, and each scenario presents its own questions about the rules of consent.

In general, there are a few rules that you can discuss with kids that can help them understand the basics of consent and help them react appropriately when faced with new situations.

Here are five simple steps to follow when teaching kids about consent:

1. Teach Them How to Ask for Consent

For the most part, kids aren’t in the business of purposely hurting others.

If a child physically interacts with another child without asking (whether that is taking another child’s toy, hugging them, pushing them out of the way, and so forth), it’s usually because they haven’t been taught yet that they are supposed to ask for consent.

It’s easy to respond retroactively to a child who has already physically interacted with another child and gotten a bad response. For example, if a child hugs another child and that child begins to cry, we might be more inclined to respond than if they hug and nothing happens.

That is to say, we don’t usually view something as a “problem” until it is a serious problem. Kids act on impulse, and sometimes they do things that aren’t appropriate without realizing that their actions are inappropriate. This is where teaching kids to ask for consent first is important.

Teaching kids to ask “Is it okay if I…?” before touching another person is essential when we are attempting to help them understand consent.

Kids should be taught to ask this question anytime they are going to physically interact with another child.

Not only does this help them understand that it’s important to ask for permission before touching someone, but it helps with impulse control.

When a child knows that no matter what, they must ask for permission before touching someone else, it creates an extra step in their thought process: Instead of going from wanting to grab someone’s arm to immediately doing it, they are forced to take a moment to think in between those two actions.

2. Let Them Know That Consent Can Be Given or Taken Away Anytime

One aspect of consent that is often met with confusion by children and adults alike is whether or not consent can be taken away once it is given the first time.

In short, yes. It can.

Just because someone gives you consent to touch them once doesn’t mean that their consent is indefinite. Consent can be removed at any point during any interaction.

This is frequently skipped over when we talk about consent to kids because it is something that we, ourselves (both individually and as a society), still present as something ambiguous.

One fear that many survivors of sexual violence have when considering whether or not to report their assault is that they worry that if they have previously consented to physical contact with their assailant, then any subsequent physical contact with that person is lawfully allowed, whether they consented in the moment or not.

We see this a lot when we look at partner sexual assault and date rape. Because the victim has a familiarity with their rapist, they believe that person has a right to physical contact due to the nature of the relationship.

It’s important to explain to children that even in the middle of a physical encounter, consent can be removed, and consenting to one form of physical contact does not automatically mean that you have consented to every physical action.

Consenting to a hug does not mean that a person has also consented to a kiss or any other form of physical contact, and familiarity with a person does not equal consent either.

When we discuss this with children, it is crucial to explain the importance of checking in — frequently — with whomever they are interacting with to make sure that what they are doing is okay.

3. Discuss the Importance of ‘No’

Giving and removing consent should be the same between children, as well as between children and adults.

A child should never be forced to interact physically with an adult. Ever. Yes, even in cases where the adult is a relative, family friend, teacher, coach, and so on.

When discussing consent with kids, you should let them know that they are under no obligation to be hugged, kissed, touched, or otherwise physically interacted with by another person, no matter the relationship.

Often, we force kids to give hugs to relatives, receive a pat on the back from a coach, or give a kiss on the cheek to a family friend because it seems harmless. In the event that a kid says, “I don’t want to,” they are often met with disapproval — and then are forced to do it anyway.

Not only does forcing a child to do these things tell the child that “no” is not an acceptable answer, but the implication is that their refusal is not respected or validated. What this can do is create a situation where a child believes this not only in regard to people that they know, but also in regard to interacting with people that they don’t know.

In some cases, a child’s aversion to being touched by a particular person might even be cause for alarm.

If a child expresses that they do not feel comfortable being touched by someone, their feelings should be validated, and then you can have a discussion about the reasons why the child does not feel comfortable around that person.

The conversation about the importance of “no” should not be one where kids are told, “Don’t ever let a stranger touch you if you don’t want them to.” It should be one where kids are told, “You don’t have to let anyone touch you if you don’t want them to.”

4. Help Them Understand the Difference Between a Non-Response and Enthusiastic Consent

The definition of enthusiastic consent is this: an active, visible, undeniable “yes.”

Usually the idea of enthusiastic consent falls under discussions of sexual interactions. However, introducing the idea of enthusiastic consent when discussing consent with children can combat much of the ambiguity that they might face down the line.

Discussing enthusiastic consent doesn’t necessarily have to be discussed in regard to sexual acts. Rather, the discussion with kids can be about the fact that a non-response is not the same thing as someone saying “yes.”

An inability to vocalize a “no” can happen for a variety of reasons: fear of repercussions, feelings of discomfort, a disability, and so on. So it’s important to explain to kids that just because someone didn’t say “no” does not mean that they are definitely saying “yes.”

This goes to the previous point about always asking for permission to touch someone else. If one kid asks another kid for permission to hug them, if the second kid doesn’t say “no,” that doesn’t mean that hugging them is okay.

What needs to happen before physical contact is made is for the kid to say, “Yes, it is okay for you to hug me.” If the “yes” doesn’t happen, then they shouldn’t be touched.

This is how you teach enthusiastic consent. It doesn’t matter the circumstance. If someone does not respond with a “yes,” then you do not touch them.

5. Follow Your Own Rules for Consent

Children are impressionable. Therefore, as an adult, you have to follow your own rules for consent.

Kids watch adults to learn the appropriate ways to interact in their own interpersonal relationships.

If you don’t ask for consent, if you ignore the word “no,” or if you force consent upon another person, it won’t matter what you tell a child because the rules will become invalidated by your own actions.

You should never force a child to physically interact with you without first asking for their consent. If they say “no,” you shouldn’t tell them that they’re wrong or force them to interact with you anyway.

In addition, the rules for consent that you discuss with a child should be enforced in all situations. Kids should understand that it doesn’t matter if they are at home, at a friend’s house, at school, or on the playground — the rules about consent still apply.

Permission Rather Than Forgiveness

Conversations about consent – especially if those conversations are with children – are not always easy to have.

They are, however, necessary if we’re trying to create a society in which consent is understood and respected by adults and children alike.

It is important to begin talking having these discussions with kids when they’re young so that the decisions that they make as they proceed through adolescence and adulthood are informed by their understanding of what it means to give and receive consent.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Michelle Dominique Burk is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. Michelle is a recent New York City transplant pursuing her MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University. She has published articles on Thought Catalog and Esteem Yourself online magazine. In her free time, she enjoys pop culture analysis and contemplating time travel paradoxes.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more