Source: Atlanta Black Star

Originally published on The Body Is Not An Apology and cross-posted here with their permission

I am not a fan Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and the way that most people interpret it.

Most folks forget that the beginning of the speech focuses on the failure of the white supremacist American government to fulfill the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation and of democracy for all its people.

But I really cringe at the line “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

I wish Dr. King could come back and do a redo because that statement has been adopted and celebrated for the wrong reasons.

The original statement has been twisted to imply that there is something inherently wrong with blackness and that great effort has to be taken to overlook it and not judge someone by it.

What Dr. King meant to say was “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by negative perceptions of the color of their skin – negative perceptions rooted in delusions of white superiority.”

An ugly truth about myself is that I used to love being the token.

Like the character Token in South Park, for most of my elementary and middle school years, I was the only African-American and non-white person at a private Presbyterian school.

I don’t know much of the history of the school, but it was founded in 1971 – I imagine as a response to school integration, like many private schools during that that time.

Because I had been taken in by the delusion of inclusion, I thought I was special. I actually took “I don’t see you as black” as a compliment. I fully engaged in the politics of respectability.

I was raised learning African and African-American history that was not taught in my school. I had black dolls. At the age of 18, I was fully aware of the significance of being the first in my family to register to vote without threat of harm.

At church, I memorized and recited the works of Phyllis Wheatley, Langston Hughes, and Fredrick Douglass. Even with all of that, my blackness was still something that I thought I needed to overcome.

I went to public school for high school. Despite my grades, guidance counselors wanted to track me into lower level classes. Even today, despite ability, African-American and Latinx students are routinely tracked to lower level classrooms because of the quiet bigotry of lowered expectations.

My mother, who was a teacher, insisted that I be put in the upper level classes. At this point, my feelings of specialness began to unravel. To my surprise, I wasn’t the only African-American student in these classes. I was one of three.

My pathology was so deep that I experienced their intelligence as a threat to my status as “the only one.”

This feeling of specialness continued to unravel when I was in college. I went to a predominately white college and, for the first time, became conscious of how I was being “otherized” by white supremacist pathology.

White men who proudly claimed they didn’t see color were clearly attempting to have their anthropological experience with me. When one white guy I went out with told me I was exotic, I was taken aback and replied, “But I’m from Georgia.”

I was consistently asked if I were there on an athletic scholarship – even though it was well known the school did not award such scholarships. I was asked if I could tan, why the palms of my hands and the soles of my feet were a different color. Some challenged my right to be there; I apparently had stolen some more qualified white person’s spot.

I was confused with other black women on campus who I didn’t even look like. When I would correct them, some white people would actually argue with me. It was a level of audaciousness I’d never experienced before.

Asian American and Latinx/Hispanic friends had equivalent experiences. Now we have a term for this phenomenon: racial microaggressions.

These responses are based on the delusion of “whiteness” as normal.

But just because something has been socially and politically constructed to be dominant doesn’t make it normal.

This line of thought is based on ethnocentrism and racism, and it is still dominant, particularly in Hollywood.

For example, in a screenwriting class at well known university in Los Angeles, I was working on a zombie romantic comedy that had a very diverse cast. I identified the race and ethnic backgrounds of all the characters in my scripts. This was my bit of resistance.

I had read a lot of scripts, and it had always annoyed me when only the people of color were identified. After reading some pages, the only note the teacher gave me was, “Oh, you don’t need to identity the white characters because white is normal.”

I looked at him like the fool he was and said, “What do you mean?”

He smiled and said, “Normal. The majority.”

I said, “Actually, since folks from China and India compromise the majority of the world population, they’re normal.”

He brushed it off with “Well, you know what I mean.”

Yeah, bigot, I do. And make no mistake, this is bigotry. It may not be the Klannifed version, but it’s bigotry nonetheless.

As I’ve worked to dismantle my own internalized racism and the ways that I privilege whiteness, I’ve learned to resist being “othered” through the use of language.

So when someone says “Oh, they did that to you because you’re black,” I quickly correct them with “No, they did that because they are bigots.”

This often shocks people. I can see the panic in their eyes. Sometimes, their eyes dart about. If there are lot of people, they may get quiet. Sometimes, someone will try to lessen the blow of my words with some clever deflection. I then come back with, “No. They are bigots.”

I name the problem. Trayvon and Michael’s blackness wasn’t the problem. The problem was the negative perceptions of that blackness and what spaces that blackness was “allowed” to occupy.

These perceptions are supported, funded, and reinforced by institutionalized racism. Matthew Shepard wasn’t murdered because he was gay. Sakia Gunn wasn’t murdered because she was a lesbian. Matthew and Sakia were murdered by people who made a choice to exercise their bigotry within a culture that deemed Matthew and Sakia “others.”

In a recent class discussion about standardized testing, someone brought up the film Stand and Deliver. We were discussing how standardized tests can have a cultural bias and ways in which test developers, administrators, and teachers could alleviate that bias.

The person who brought up the film said that the students were required to take the test again because cheating was suspected.

I filled in the blanks of his statement by saying, “The only reason cheating was suspected was because of the lowered expectations of those administrators had for the Mexican-American students.” These lowered expectations were forced upon the students.

The microaggressions that many people of color experience at the hands of some white folks may not be laced in what we think of as hate.

Hate may even be too harsh a word. But they are laced in subtle notions of superiority and indifference that in many instances cause more harm.

For a person of color, there is no winning this game.

When lowered expectations are met, the point is proven and the supremacist narrative is further reinforced. When you exceed expectations, it’s a surprise and can lead to resentment and sometimes, outright hostility – think: President Obama.

I choose not to play. I no longer want to be a token or to strive for validation within white, ethnocentric, heteronormative spaces. These narrow spaces don’t represent my values or me. Other people’s negative perceptions? Not my problem.

Now, this doesn’t negate the very real negative impact of these overt and covert forms of bigotry. When bigots project their negative perceptions, they are trying to make their pathology my problem.

However, recognizing and naming the problem goes a long way into dismantling the internalized forms of these bigotries. I can embrace my culture and my identity as well as respect and celebrate the culture of others.

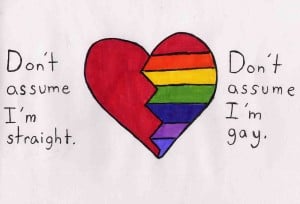

I don’t see differences as threats, something to be tolerated, or even ignored. Differences are to be respected, honored, and celebrated. This is what Dr. King was actually dreaming about.

***

To learn more about this topic, check out:

- 5 Reasons White People Don’t Have to Hate People of Color to Be Racist

- On Ferguson and 4 Ways We Can Choose to Divest from White Supremacy

- Why It’s Not Racist When People of Color Point Out White Supremacy in White People’s Actions

- For Michael Brown and Ferguson: Facing White Fears of Blackness and Taking Action to End White Supremacy

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Toni Bell is a Georgia native a documentary film researcher and a sometime licensed massage therapist, an adult beginner cellist, and a writer. She received her an M.F.A. in creative writing at Naropa University and a certificate in Professional Screenwriting from UCLA. One of the screenplays she started in that program placed in the quarterfinals of the 2013 Academy Nicholl Fellowship. She’s currently working on MAT-TESOL in USC to fulfill another one of goals: to live overseas.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more