Young indigenous girls are drowning in the negativity surrounding them.

Recently, several teenage girls on my reservation in South Dakota made a suicide pact, which is sadly not an uncommon occurrence in Indian Country.

The epidemic of youth suicides and attempts prompted tribal officials on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation to declare a state of emergency in February 2015.

As an indigenous mother of a six-year-old daughter – and as someone who survived sexual abuse as a child, and rape and suicide attempts as a teenager – confronting the reasons behind this hopelessness (and doing something to change it) is of the utmost importance to me.

We’ll probably never narrow down exactly why these girls decided overdosing on pills was the answer to the issues they faced, but acknowledging and standing against the many oppressions attacking young, indigenous girls today are good initial steps to take.

The hypersexualization of indigenous women is at the forefront of these oppressions.

How our daughters see their culture and themselves represented in the media, how products are marketed to them, and how society built on colonial violence treats them in real life affect every aspect of their existence.

The following includes tools and information to help caregivers and others support and strengthen indigenous girls.

What Is Hypersexualization?

First, it’s important to understand and recognize what hypersexualization is and how it shows up.

Many organizations, including the American Psychological Association, put sexualization and hypersexualization on the same level and define it within many layers of sexual objectification, value based on an individual’s perceived sexual worth, and imposing sexuality without consent (especially on young people).

Hypersexuality is not the same thing as healthy and normal sexual behavior, including self-exploration and masturbation, and providing children with on-going, age-appropriate information regarding healthy sexuality is a must for any parent.

Finding examples of hypersexualization isn’t hard. A stroll through your favorite department store or turning on your TV will render countless results:

- Underwear for a six-year-old can have words like “Flirt” or “Diva” written on them.

- Anatomically questionable dolls wearing gaudy make up, high heels, and party outfits are marketed to children 3-8 years old.

- The worth of female characters on kids’ TV shows or in movies is often based on their ability to attract the attentions of males.

Focus those images and products on indigenous girls, specifically, and at best, there is no representation (also harmful – do we exist?) and at worst, the representation is an idealized objectification of the Indian princess stereotype.

Why Is Hypersexualization Dangerous?

In general, these products and images teach young, impressionable girls what the standard is they should be reaching for. It normalizes misogyny and sexualized behaviors, making girls more at risk to violence.

For Native girls, their culture is fetishized and sexualized as it’s displayed on (often) white, appropriating bodies (see Karlie Kloss of Victoria’s Secret, Gwen Stefani of No Doubt, Disney’s Pocahontas and Tiger Lily characters, and pretty much any Halloween costume ever designed).

Beyond the hypersexualization is the pervasive stereotype that the Indian princess is one who needs to be rescued by the white, cowboy-ish hero (Peter Pan, John Smith, John Dunbar, and Jake Sully).

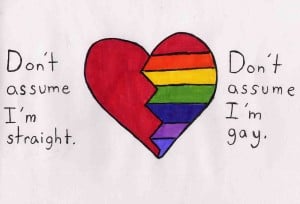

The message is not only that a Native girl’s value lies in her exotic, leather-clad (yet idyllically Western) body, but also that heteronormativity – a system of ideas that reinforce heterosexuality and rigid gender roles for men and women – is the foundation upon which relationships stand.

This is important: Adherence to cis-gender identities and sexualities is a product of colonialism we’re slowly moving away from, as many of our traditional beliefs highlight a vibrant gender spectrum known in modern times as Two Spirit.

But despite truly beautiful traditional belief systems that welcome Two Spirits and value women, Native communities today continue to struggle with homophobia, sexism, child abuse, and gender-based violence. Because media images have power.

These images seep into the psyches of our children – our daughters and our sons.

Harm isn’t the risk, but the expectation.

A Native mother I worked with in South Dakota told me she prepared her daughter for when rape happened, not if.

And why wouldn’t a good Native mother take this kind of action when the odds are stacked against us:

- In the US, Native women are murdered at ten times the national average.

- One out of every three Native women will be raped in her lifetime.

- Physical assaults, stalking, and harassment are more than twice as likely if you’re a Native woman.

According to the Indian Law Resource Center, where these statistics are from, data regarding violence against young Native girls is pretty much non-existent and incidents of violence are under-reported.

What Can You Do About It?

Though sometimes tempting, locking our daughters in a high tower to keep them from the world’s evils isn’t an option.

And in terms of violence, I’d like to believe we can make this a world where we can teach our daughters safety using language like “if,” not “when.”

I have found the following to be practical and useful tools in my efforts to support my daughter in a world that tells her to be sexy and to expect violence.

1. Limit Exposure to Media and Products That Hypersexualize Her

We don’t have a TV or use cable in our home, although we’re longtime supporters of streaming services to our computers and smart devices.

Not having ads and commercials in my daughter’s face means the latest toys and fads aren’t really on my daughter’s radar. But thanks to peers, family, and shopping, she knows about Bratz, Monster High, Barbie, and most of the popular stuff.

She asks to engage with these products, and together we’ll check out an episode or merchandise with a feminist and indigenous lens. I ask her questions about body proportions, diversity, or a character’s gender identity, among other things.

We spend quite a bit of time discussing the cues (read: stereotypes) that help her come to an answer. For example, color-coded toy aisles are marketed as “just for boys” or “just for girls,” and we talk about why this is unfair and simply not true.

When she asked to be the red Power Ranger (the quintessential male character of a show she enjoys) for Halloween last year, I knew our talks were settling in.

This might sound overwhelming or time-consuming; trust me, my daughter and I aren’t having college-level philosophical discussions here. Our conversations can take anywhere from 30 seconds to five minutes. She really doesn’t have the attention span for more than that.

The point is to continue the dialogue. Daily. Weekly. Whenever she brings it up or whenever hypersexualization gets shoved in her face.

With movies or TV shows, we try to follow the Bechdel Test. If it’s clear the story focuses too much on looks or attracting boys or some other inane trope, we turn it off, and we talk about why.

I find that if she can come to the same conclusion with me, on a journey, as we watch or experience a product together, she’s more likely to “get” how problematic the message is, and choose for herself to consume healthier material.

Just like we are constantly discussing body safety and autonomy, I devote time to reviewing examples of hypersexualization with my daughter and help her embrace not only why I limit her exposure to those products, but also why they hurt girls like her.

2. Encourage Her to Know and Love Her Own Body by Modeling the Behavior

There are few times when my daughter and I are together when we want to be apart.

She’ll spend time with me in the bathroom or as I’m getting ready for bed, and sometimes she’ll ignore me and do her own thing and other times she’ll ask about what she sees on my body or her own.

My goal is always to be as anatomically accurate and body-positive as possible.

We talk about differences: She’s short, I’m tall; I weigh more than she does; and her skin is darker than some people, but not as dark as others.

We talk about how strong our bodies are because of the energy we consume and expel.

And I never compare us or other girls to a stereotyped ideal.

I do not talk about ugly fat, or what clothes fit and which don’t. The word “diet” (as in weight loss) is a four-letter word in our home. And, though it’s a challenge sometimes, my daughter doesn’t constantly hear how beautiful or pretty she looks.

I need her to know her worth is so much more than her appearance.

That doesn’t mean we limit her self-expression. Part of our culture’s tradition and indigenous resistance means we keep our hair long; however, my daughter has dyed hers several different shades. She also picks out her own outfits.

I just close my eyes to the fabulousness of it all.

The message I hope to impart with all this is her body is her own to touch, appreciate, and control without the influence of outsiders, whether the outsider is her favorite TV show or me.

3. Help Her Build Positive Relationships

This begins with her experiencing how a healthy relationship should function.

Her father is one of the most dedicated feminists I know, and he helps me implement this and every strategy in our home.

More than that, our daughter witnesses her parents sharing the responsibilities of earning household income, child rearing, chores, and gifting each other with alone time.

We also argue respectfully, broadcast affection for each other, and acknowledge when mistakes are made. And we make a lot of mistakes, both with our daughter and with each other. That’s okay.

Also, we are purposeful when it comes to our socializations with others. The adults in our life (and therefore hers) are strong people in their own ways, whether they are fellow activists, allies, people of color, or simply other parents we admire.

We therefore encourage her to surround herself with peers who offer the same kind of strength: Boys who embrace their femininity and will play My Little Pony with her just as soon as they’d share her red Power Ranger sword; or girls who want to explore the mountains and teach her to raise and butcher urban livestock in humane and culturally responsive ways.

This isn’t easy. We live in Colorado Springs, where Focus on the Family built its empire and a place with a heavy military presence. Diversity (of ideas, in particular) can be hard to find here, but the effort we put into building our social circle is worth it.

Having friends of different ethnicities and genders and cultures and beliefs and abilities helps her be more aware of the vast diversity of the human experience – what media and commercial products often ignore.

***

Our daughters are groomed to accept misogyny via daily microaggressions from the media and pop culture

Without guidance, they learn to base their worth on how attractive they are to men, to protect themselves against harassment with smiles and good manners, and be content with invisibility.

We empower our daughters when we continuously deconstruct hypersexualization and other messages perpetuating violence against women.

We empower them when we provide safe spaces to process these messages and opportunities to smash the kyriarchy in their own, unique ways.

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Taté Walker is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Mniconjou Lakota and an enrolled citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe of South Dakota. She is a freelance journalist who lives in the Colorado Springs area. She blogs at Righting Red and can be reached on www.jtatewalker.com. You can check her out on Twitter @missustwalker.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32