Though I hate to admit it, I was once that well-meaning White teacher – the one that comes from a wealthy family, chooses to teach in a “poor, urban school,” the one who wrote in my cover letter that I wanted to be the “engaging teacher” with a “racial justice pedagogy” who could help his Black students “overcome their tough life circumstances.”

I was the teacher who said things like, “These kids just don’t have the best educational supports at home, so we really need to step in and model for them.”

Despite my “racial justice pedagogy,” I said nothing when my colleagues complained that “these students have to want to learn if I’m going to teach!”

I don’t mean to be self-depreciating, but I “just wanted to close the achievement gap.” And, sadly, I’m not alone.

Many of us fail to acknowledge that terms like “the achievement gap” place the responsibility of change on students – and specifically poor and working class students of Color.

Yet, in my experience offering professional development to educators, most of the White teachers I work with are well-intentioned despite the damage we may be doing with these victim-blaming, deficit-oriented beliefs.

However, when at least 80% of our teachers in the United States are White and the most powerful decision makers tend to be White or are pushing White-designed models of reform, is it any wonder that we inaccurately perceive this country’s educational inequity as being the result of a student-deficit “achievement gap” – a term dating back to White “reformers” of the 1960s – rather than, say, systemic oppression and marginalization?

This isn’t to say that we aren’t trying.

Increasingly, progressive educators are looking for alternatives in our language and reform methods that actually address the root causes of our educational injustice.

But here are some things that we really need to think through if we want to really improve the system.

Who Do Our Schools Serve – And Why?

Let’s be honest: Public education was created to serve as an entry point for lower-to-middle-wealth White people into the American middle class (by preparing White students for success in industry and farming).

Schools in the United States have always been tools for consolidating wealth into White hands, even when some people of Color have found success in these systems.

Even Brown v. Board, the landmark Supreme Court ruling to desegregate schools, didn’t serve to decenter Whiteness.

The “integration” of Brown v. Board didn’t change the White supremacist roots of education; it simply demanded that students of Color enter White schools, bend themselves to White systems, and learn from White teachers.

When we see our education system through this lens, we understand that it serves not only to consolidate White power and wealth, but to ensure that people of Color cannot succeed.

Yet when they don’t, they are blamed for their own lack of “achievement” in a supposedly “race neutral” system.

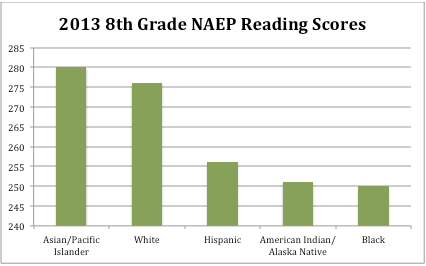

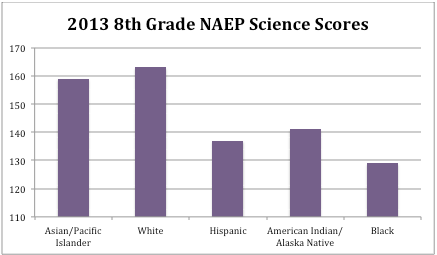

Notably the modern disparities in our educational system have come into starker contrast during this age of endless data collection from No Child Left Behind.

However, much of this data is used to judge and critique populations our schools were never designed to serve in the first place.

When we take these numbers at face value, we see that Hispanic/Latinx, Indigenous, and Black students trail their White and Asian peers by huge margins in every academic area:

Further, Asian success in the US education system is regularly used to “disprove” the idea that our schools are built upon White supremacy, but to understand Asian success in US schools is to understand the history of White supremacy that undergirds the Asian success story in the United States.

After all, the number one predictor of educational success in the US is parental education, and since the Chinese Exclusion Act, the US has let in relatively few Asian immigrants without advanced degrees.

However, when we examine the NAEP data by parent’s education, though, we see that poorer, less academically educated Asians (such as Hmong refugees) and Whites – while still outperforming Latinx, Indigenous, and Black students – struggle to find the same success as those whose parents are well educated.

And simply put, when our schools have been set up to serve Whites while excluding all but a few people of Color, it makes sense that White people are far more likely to have an advanced education.

In fact, Black men in the US actually must have a higher level of education than White men to get the same jobs, so even when those who’ve been left out of the system succeed, the deck is stacked against them!

In the face of this tremendous disparity, no longer can we avoid placing responsibility where it belongs.

The Education Debt

In her 2006 address entitled From Achievement Gap to Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings explains,

The yearly fluctuations in the achievement gap give us a short-range picture of how student perform on a particular set of achievement measures. Looking at the gap from year to year is a misleading exercise.”

Instead, we must not focus on the gaps in achievement, but must zoom the lens out to understand the broader picture where “the historical, economic, sociopolitical, and moral decisions and policies that characterize our society have created an education debt.”

When we refuse to invest properly in the education of those with the least access, we see the results in our test scores and in every other measure of injustice in our society: poverty, employment, wealth accumulation, health disparity, exposure to violence and stress, and so on.

Ladson-Billings goes on to describe the ways that each form of debt – historical, economic, sociopolitical, and moral – creates a demand for accountability that places responsibility with those who run the educational and economic systems that enforce this debt.

Thus, we have a responsibility to shift our language and approach in education away from a victim-blaming, deficit-oriented gap model and toward addressing the startling education debt.

This is of particular importance for White educators, as we are those with the most power to further entrench the debt.

Just as much as White educators tend to reify the education debt, we also have the power to help repay it, particularly when we are led by communities, parents, students, and educators of Color.

Repaying the Education Debt

Thus, drawing upon the analysis of Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, here are some of the ways that we can begin to repay the tremendous debt that is owed to students of Color in the US.

1. Address Funding Injustice

The educational debt rests upon hundreds of years of unequal funding that persists today.

While adequate funding alone cannot settle the debt, it can go a long way to providing the resources needed to create just schools.

In the school where I taught, an almost all-Black school in a neighborhood of Chicago where 99% of students live in inter-generational poverty, about $9,000 per pupil per year was spent on the students.

In the nearby New Trier High School, just 24 miles away in a mostly White suburb, spending per pupil totaled $21,000 per pupil.

My classroom had one set of textbooks for all 9th grade social studies students, while New Trier offered a rich array of courses and extra-curriculars.

Taken over generations, this unequal funding, not only in our schools but in nearby social services, creates a tremendous debt.

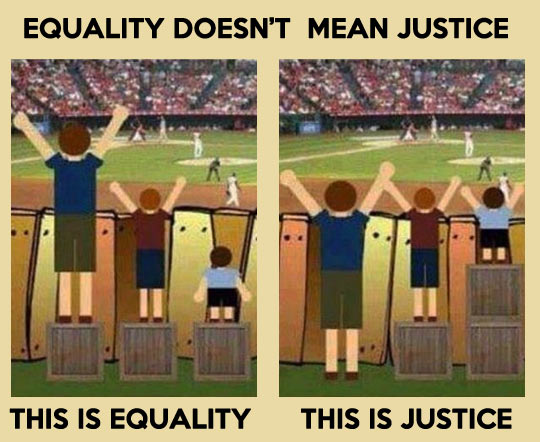

However, to repay this debt, we should not simply strive for funding equality.

There should be disparity in education funding. We should be spending more on our schools in the lowest-wealth (disproportionately Black, Brown, and Indigenous) communities than in wealthy, predominantly White communities.

That doesn’t mean that we should cut funding to wealthy, White schools. So long as we think about our problems in education from a model of scarcity, we forever lose.

However, a massive, disproportionate investment in education in our lowest-wealth communities would go a long way toward reducing class size and offering robust student resources in the least-served communities while addressing the racialized wealth debt in the long term.

As educators, we must be the ones leading the charge to address this funding inequity.

2. Address Racism in Our Measures of Student Success

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not a testing hater. As an educator, I believe tests can be useful tools for collecting and analyzing information about our educational system.

However, when we tie everything in our educational systems into high-stakes standardized tests (like the demonstrably culturally biased SAT) that are rarely created with equity in mind, we only ensure that those tests further the educational debt.

After all, who writes the tests?

They usually aren’t written by people who understand the lived experiences, vernacular, or contexts of the students most at risk for school closings and teacher turnover when the scores come back.

Formative and summative assessments, even standardized ones, can have a place in our educational system, but when they are used as our sole measures of success, we ensure that we further entrench the education debt.

So what do we do as educators?

Well, we can do what teachers do best! We can organize!

Partner with your students’ families to help them understand that they have the right to opt out of high-stakes tests. Join in the movement of teachers who simply refuse to give the tests, and be sure to cite cultural bias as one of the driving reasons for refusing.

Or think outside the box! What other solutions can you, as brilliant educators, think of to address racism in our measures of student success?

3. Address the Teacher Demographic Gap

One of the elephants in the room of educational reform is that students, by in large, learn better from teachers who share their racial identity.

While we’re so focused on the failings of our students through the “achievement gap,” we ignore the ways that our overwhelmingly White teaching force is not only ill-equipped to serve student of Color but often are actively injecting our Whiteness and racism into classrooms!

In my own teaching experience, there were countless ways that my own racial identity was showing up. Some of these ways were surely benign, but many were undoubtedly detrimental to my students.

As a society, we must attract and prepare more teachers of Color, plain and simple.

How do we do that? Direct track programs that lead into teaching professions with little-to-no student debt are a great place to start.

Additionally, we can value the knowledge and experience of people of Color who work as paraprofessionals and out-of-school time educators through alternative licensing programs.

And we can recognize that just like White teachers, not every teacher of Color will be outstanding educators, but the ability to connect with students who share their racial identity is a vital asset in effective pedagogy.

Notably, changing the demographics of our teaching force is not something that can happen over night. Thus, in the mean time, we must also devote time, energy, and resources to effectively training White educators in culturally responsive pedagogy and anti-racist teacher practice.

4. Work to Address Those Inequities That Contribute to the Education Debt

When I taught on Chicago’s West Side, I would often talk with my students and their families about how much more effective schools would be if they were integrated centers of health (physical and mental), childcare, housing, job training, and recreation.

To compartmentalize the education debt and pretend it is not inextricably bound to debts in other areas of wellbeing doesn’t help us solve the problem.

In The Many Dimensions of Racial Inequality, Richard Rothstein and Tamara Wilder explore how the debt we owe communities of Color in education cannot be extricated from what we as a society owe them in terms of wealth, health, housing, early childhood supports, out of school supports, and safety.

Single-issue movements can be defeated simply, so we must work for wrap-around school services that meet all of the needs of communities of Color.

As teachers, we must look for ways that we can partner with those doing intersectional social justice work in the communities where we teach.

Can you advocate with community organizations for your school building to serve as the host for continuing education classes in the evening? Can we partner with organizations working for health care justice to offer clinic space in our schools on weekends?

It won’t be easy or simple to create wrap-around school systems, but in creating them, they must be envisioned, created, and led by local people of Color with ample resources to realize success, which leads us to my final point.

5. Envision and Create Schools Where People of Color are Centered (And Whiteness Is Not)

As noted above, “integration” under Brown v. Board was more about making people of Color bend to White supremacy than actually creating just schools.

And educational reform has been almost exclusively directed by White academics and activists (people like me), and as such, most major reforms have done little more than to dress up our White systems and ways of being in new clothing.

In turn, we White folks, but particularly White educators, need to trust that communities of Color know what is best for their educational liberation.

This is by far the most abstract of my six suggestions, for there are few school environments that have managed to achieve this radical shift. Especially for White educators, this is like a fish imagining what it’s like to breathe above water.

So I look to and trust the scholars and leaders of Color, many of whom are linked throughout this piece, to lead the way, and we must do our best to work in solidarity.

With that in mind, I will close with this quote from Black legal scholar Randall Robinson:

No nation can enslave a race of people for hundreds of years, set them free bedraggled and penniless, pit them, without assistance in a hostile environment, against privileged victimizers, and then reasonably expect the gap between the heirs of the two groups to narrow. Lines, begun parallel and left alone, can never touch.”

[do_widget id=”text-101″]

Jamie Utt is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Tucson, AZ. He is currently working toward his PhD in Teaching, Learning, and Sociocultural Studies at the University of Arizona with research interests in the role that White teacher’s racial identity plays in their teaching practice. Learn more about his work at his website here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more