I’m a proud Black feminist, but sometimes I get really tired of feminism – especially mainstream feminism that likes to accuse Black women of being divisive for bringing up racism.

As if the movement hasn’t been silencing, disregarding, and rejecting our leadership and needs from the beginning.

And yet I never gave up on what feminism has the potential to be. It took me years to cultivate a feminist practice that nourishes me, and in the process, I’ve had to filter through too many forms of feminism that weren’t willing to make space for someone like me.

So anyone who thinks I’m being “divisive” by distancing myself from everything I’ve filtered through hasn’t experienced feminism like I have. I took three different dives into various worlds before I could understand how the feminist movement relates to me.

Round one was the “I’m a woman, so I’m a feminist!” stage.

I had just finished my first women’s studies courses in college, where I learned about patriarchal oppression and finally got validation with a name for the gender inequality I felt in the world.

I was so thrilled to find a movement fighting for my rights, for my freedom to be myself, and for the space to be someone other than a stifled model of what the patriarchy wanted me to be. It didn’t take long at all for me to decide I identified with feminism.

Round two was my “But I’m a Black woman, so am I a feminist?” stage.

At this point, I began to notice that the literature and ideology I was so hyped about seemed to be missing something critical – namely, an analysis of race. Or any recognition of racial justice issues, for that matter.

Every time I attended one of the meetings for the feminist groups on campus and looked around at the mostly-white faces in the room, I couldn’t help but wonder if this movement was for me after all.

Then came round three, the “I’m a Black feminist, and it’s complicated” stage.

I found out where the Black feminist writings had been “hiding” – in my creative writing classes. And when I followed poetry’s leads to read the work of writers like Audre Lorde and Cheryl Clarke, I realized they hadn’t been hiding at all.

Instead, they were silenced by the dominant narrative of what feminism was all about and completely shut out of my Women’s Studies courses.

Through reading the works of these Black women, I learned about a history of white feminists overlooking, putting down, and shutting out feminists of color, and about the consequent womanist movement Alice Walker founded for Black women tired of mainstream feminism stepping all over them.

And despite all of the work done by these poets and thought leaders, mainstream feminism still has a lot of changes to make before it can be an actual resource for Black women’s needs – in fact, the way white supremacy and the patriarchy collide against us is often replicated within mainstream feminism.

As Black feminists, we encounter harmful language and actions from self-identified feminists. Some of this harm even comes from people who say they have good intentions.

Then, when we tell them about our pain, they say we’re overreacting, leaving us wondering if we’re too sensitive.

But we’re not too sensitive. White feminism is too racist – which is intensely clear when white feminists ignore our frustration.

Here’s the truth about several common phrases that actually hurt us – and the reasons that you’re not being divisive, or too sensitive, if they bother you.

1. ‘We’re All in This Together’

Doesn’t that sound swell?

While this phrase is offered as a show of solidarity, mainstream feminists often fail to do the action to back it up.

If we were “all in this together” to address the gender wage gap, for example, then there wouldn’t be so many feminists saying that “women make 77 cents on the dollar in comparison to men.”

That figure only represents what white women make as compared to white men. When feminists fail to recognize that Black women make only 64 cents to a white man’s dollar, it’s hard to imagine that we’re supposed to be “in this” for us, too.

Sometimes, being “in this” with mainstream feminist campaigns actually means supporting harmful institutions.

For instance, pro-choice campaigns have worthy goals of increasing access to abortion care. But Margaret Sanger, called the founder of the birth control movement, also advocated for eugenics, a racist ideology focused on wiping out people of color.

Many leading pro-choice advocates won’t acknowledge this awful history or address the impact it still has today – like forced sterilization of Black women. Instead, they’ve lead a movement that hurts many of the people relying on reproductive justice.

So if you get this response when you bring the relevant issue of race into a conversation about a “women’s issue” like the wage gap or reproductive justice, you can say what’s really going on – looking out for all of us means looking out for more than just white women.

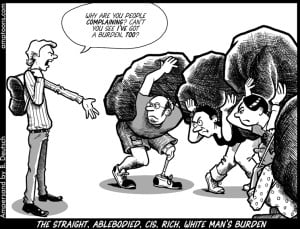

2. ‘We Need Unity’

This is another phrase that shows up as a fake show of solidarity. Unity’s nice, but unfortunately, this particular sentiment is bullshit.

In mainstream feminism, the concept of uniting to support “women’s issues” usually manifests as focus on white, middle class, cisgender, able-bodied women.

These days, the dominant narrative of how we should unite is what’s known as “white feminism” (insert #NotAllWhiteFeminists disclaimer here).

Cat Young wrote for BattyMamzelle about what she means when she says “white feminism,” describing it as “’one-size-fits all’ feminism where middle class white women are the mould that others must fit.”

The rest of us shouldn’t have to set aside our own needs in the name of unity.

And stepping over marginalized voices to pursue a narrow vision of equality is not a cause worth uniting over.

3. ‘Why Do You Hate White People?’

Without understanding why in the world someone would object to “unity,” some white feminists reach the conclusion that Black feminists who speak out against racism are actually anti-white.

Words like “attacking” and “shaming” and “bashing” come up in these reactions – not in reference to the racist behavior that causes harm, but as accusations against those who call that behavior out or in.

It’s not racist to bring up race. You’re not being divisive by helping the movement grow as one that contributes to liberation for all people.

White feminists must do their own work of unlearning racism, and it’s not our job to do it for them. But we do have every right to speak up when they’re contributing – intentionally or unintentionally – to the anti-Black oppression we face.

4. ‘Not All White Feminists’

It’s hard to speak up about racism in the feminist movement when everything you say results in a knee-jerk response that “not every white feminist is like that.”

I can understand that white feminists don’t want to be swept up in generalizations (we sure know how that goes).

But this echoes the #NotAllMen efforts to discredit women speaking up about gendered violence by pointing out that not every man attacks women.

Just like the “not all” men, white feminists who say “not all white feminists” derail the conversation – so we’re no longer focusing on the real issue of racism, but on reassuring each white feminist that they are not, personally, responsible for the oppression of Black women.

This derailment totally misses the point – because addressing racism in feminism isn’t about telling individual feminists that they’re bad people.

It’s about dealing with the very real ways the system of white supremacy shows up in the feminist movement.

You speak up about racial injustice because you know about the harm it causes, and you know you deserve better than to have to put up with that harm.

You also don’t deserve to have people distract from what you’re saying or refuse accountability for their actions with “not all white feminists.”

So stick to your point, even if it means leading people to face uncomfortable truths.

Also know that it can be really damn difficult to talk about racism with a white person who denies its existence. So while you don’t have to back down from your point just because they refuse to listen to it, walking away for the sake of your own self-care is perfectly valid.

5. ‘I Don’t See Color’

If someone tells you “I don’t see you as Black,” don’t be alarmed – your melanin hasn’t vanished. They mean to say they’re not racist.

I know, it’s a strange way of going about it. Because if someone says they don’t recognize my Blackness – like that’s a good thing – they’re implying that my Blackness is a bad thing.

But it’s not. My Blackness is beautiful, and it’s an integral part of who I am, and it’s shaped my experiences every day of my life.

Claiming to be “colorblind” erases all of that.

By refusing to recognize how my identity is distinct from the dominant white narrative, “colorblindness” assimilates me, against my will, into that narrative. As if whiteness is the default, and what I should aspire to be.

This is not only a personal insult to me – it’s also a dangerous way of going about addressing injustice.

For instance, if white feminists don’t see race when they take on rape culture, they might urge reporting sexual assault to the police as a solution to ending sexual violence.

If, instead, they prioritized centering survivors of color, they might talk to somebody like me. I’m a Black survivor, and the police make me feel more unsafe because so many of them ignore or re-traumatize Black survivors.

So if you’re bothered by the phrase “I don’t see color,” you have good reason.

Point anyone who can’t understand why to Kat Blaque’s incisive explanation of how that statement misses the difference between equality and justice.

6. ‘Well, I’m Not Offended’

Have you ever witnessed or been subject to a Council on Black Women’s Feelings?

That’s what I’ve dubbed the process when white feminists convene to determine the validity of a Black woman’s experience with racism.

For example: a Black feminist objects to a white feminist saying “all lives matter.”

Then other white feminists come to the first white feminist’s defense, arguing that because they recognize her good intentions, and know she didn’t mean to be racist, the Black feminist’s account of oppression is somehow wrong.

The Council on Black Women’s Feelings is messed up because it invalidates the knowledge and emotion that naturally result from a lifetime of oppression.

We’re accused of being excessively angry for pointing out how we’ve been wronged.

If we’re only allowed to act on oppression when white women approve, then anti-Black racism will continue unchallenged, with a black person killed by police every 23 hours while we argue for the right to simply say that Black lives matter without being derailed.

That’s not feminism – not the feminism that Black women helped build as a justice movement for all people.

Know that your feelings are valid, and the Council on Black Women’s Feelings has no authority on issues of anti-Black racism.

7. ‘I Support Women of Color, But We’re Feminists – Why Do We Have to Talk About Racism?’

Speaking of #AllLivesMatter, there are some who would prefer for race to be left out of feminist conversations altogether.

While they wonder how race is relevant to gender equality, I wonder how they could possibly expect me to separate my Blackness from my gender.

There’s a reason Black women began the Black Lives Matter call for action to end police brutality, why we stand on the uprising’s front lines, why we remind the world of the need for Justice for Rekia Boyd and other Black women and girls who are killed by police – but are ignored in many conversations about state violence.

Racial justice work is essential for our survival, and we shouldn’t have to pretend it’s not a core part of our lives when we address gender justice.

Including race in our conversations about gender justice will strengthen feminist causes because women of color can participate knowing this is about our wellbeing, too.

8. ‘This Makes Feminism Look Bad’

This phrase isn’t used exclusively by white feminists to Black feminists, but it does play a big role in white feminist criticism of how Black women express ourselves, fight for justice, and develop our strategies for survival.

For instance, some feminists believe celebrities like Laverne Cox and Beyoncé hurt women’s causes through their expressions of femininity and sexuality.

Others criticize the use of online tools like Twitter to create social change, dismissing the influential digital activism of Black Twitter figures like Mikki Kendall, Feminista Jones, and Shaadi Devereaux.

White feminists don’t know better than we do about what’s best for us (regardless of what their white savior urges might tell them).

When entertainers like Amy Schumer and Lily Allen exploit Black women’s bodies to make “feminist” statements, they reveal the danger of white women’s dominant voices in conversations about feminist respectability.

Black women are shamed for our self-expression, blamed for the feminist movement’s mistakes, and told our choices make us less valuable to the movement.

None of this holds true, but it adds to toxic anti-Black messages about our value in the world.

To stand up to those messages, let’s continue to fiercely love ourselves and each other through a feminist practice that values our leadership.

9. ‘Feminism Doesn’t Have a Race Problem’

Ever heard someone say “Come on in, the water’s fine,” when you knew damned well that water would freeze your fingers off?

In spite of all these problems, you’ll still come across white feminists who insist that there’s no racism in the feminist movement.

They’ll respond to a racist incident as if it’s one-time mistake, rather than a symptom of an ongoing issue. Or they’ll deny that a harmful incident is racist at all.

By refusing to recognize racism, white feminists avoid unlearning their own implicit biases.

Feminism’s race problem doesn’t just exist in our imagination, and claiming that it does is insulting to an entire legacy of Black feminists who have worked so hard to fight for our needs from the past through present day.

It’s up to the mainstream feminist movement to catch up to the revolutionary work of change-makers who pursue gender justice without upholding other forms of injustice in the process.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Maisha Z. Johnson is the Digital Content Associate and Staff Writer of Everyday Feminism. You can find her writing at the intersections and shamelessly indulging in her obsession with pop culture around the web. Maisha’s past work includes Community United Against Violence (CUAV), the nation’s oldest LGBTQ anti-violence organization, and Fired Up!, a program of California Coalition for Women Prisoners. Through her own project, Inkblot Arts, Maisha taps into the creative arts and digital media to amplify the voices of those often silenced. Like her on Facebook or follow her on Twitter @mzjwords.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32