George Zimmerman had just been acquitted in the shooting murder of Trayvon Marin.

Remembering the memory still makes my heart race, my skin crawl, and the insides of me burn like hot coal. I don’t know that I have ever felt rage – true rage that awoke my ancestors – until that moment.

That night, I sat in silent, seething rage for what felt like hours. It probably was. My white friend who was with me at the time knew he couldn’t offer any words to soothe me, so he just sat with me quietly.

After some time, I got up, laid in my bed, and wept. It was the body-shaking type of weeping that left me gasping for air. They can’t kill us all! my mind screamed, again and again, as I lied in my tears until I fell asleep.

And then came the dreams – the terrifying nightmares of lynching, floggings, shootings, sirens. Excessive images of the centuries old violence that is repetitively bestowed upon the bodies and spirits of my people.

This rage and agony (as well as strength and resilience) is in my blood stream.

Trayvon’s murder awoke in me an anger that was too hot to extinguish and that had to be put somewhere. I just didn’t yet know where.

And at the time I was in Santa Cruz, passing faces who appeared happy, indifferent, unaffected. I was reminded that, even in the face of tragedy that felt deeply personal, life went on for so many other folks.

It felt like was away from a place to share my pain and anger with people who could actually understand it. Or so I thought.

I caught word of a rally and march organized by Black students’ organizations on campus, and found enough strength to show up. I arrived at the gathering, where a group of mostly Black students, staff, and community members recited words in honor of Trayvon and in condemnation of the acquittal.

I felt the pain, frustration, and rage in their voices and tear-stained faces. This space not only provided me the opportunity to mourn the continued loss of Black life – it also showed me that our pain was collective. None of us were alone in our rage and in our hurt.

And then we moved the rally into the streets of Santa Cruz – marching through the campus and all the way through the small downtown area. Some of us silently marched in tears, others chanted.

We were welcomed by cars honking in either approval or irritation. Onlookers raised up firsts in solidarity, and some moved from their homes and sidewalks to join the march.

This action was healing and unifying. It gave me the space to grieve with other people who looked like me – or who didn’t but still refused to be complicit. It showed others in this small town (and beyond) that we would not be silent while the “justice system” continued to dehumanize oppressed people.

It re-awoke in me an anger and hunger for liberation that spread like wildfire. And direct action was only one way I’ve learned transform this anger into change.

Why Direct Action?

I have been involved in many direct-action protests, disruptions, marches, and other demonstrations before and after Trayvon.

Direct action has the power to make private grief public and to demand an end to continuous violence.

And those of us who participate in “in the streets” forms of direct action know that we will be the targets of criticism, emotional and physical violence – that even people who may claim to be “sympathetic” to our cause are the same that are angry about #BlackBrunch.

We know this.

Most of us shutting down city council meetings, or interrupting President Obama’s press conferences, or blocking traffic to end incarceration and deportations, know what both the cost and benefits are.

Direct action is about disruption and courage – it demands that you acknowledge us, even for five minutes.

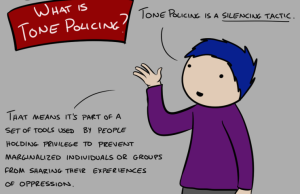

The often hostile criticism that activists receive for taking action is often seeped in privilege and indifference to others’ suffering. And the indifference needs to be called out.

Below are just some of the questions and comments I’ve commonly heard in response to direct action.

1. ‘Why Can’t You Peacefully Ask For What You Want?’

A group of all-Black activists did a Valentine’s Day action in the town of Walnut Creek, a predominantly white and upper-class neighborhood with a history of white supremacist politics and rallies.

We took over local businesses to call out the names of Black people who had been murdered by the police. We demanded an end to complacency.

We spent no longer than five minutes in each restaurants surrounded by white folks who refused to look at us – some plugging their ears, others calling out slurs, others mumbling that we “deserve to be shot.”

None of us carried guns, none of us threatened anyone (aside from our presence as Black), and no one was harmed. That being said, the action was not “peaceful” because it wasn’t intended to be.

A few days later, amidst allegations that we “bullied and harassed” people, a former peer (and aspiring police officer) sent me a long message expressing his outrage at what we had done.

He asked me why we could not take a “less Black panther” approach and instead be more “peaceful” – maybe handing out flyers or working directly with the police department. (I wondered if he was talking about the Black Panther party that provided free meals and education to entire communities of Black children, but decided, probably not).

I responded that, any time a group of Black people go anywhere to do any thing, we are automatically assumed violent or suspect.

We are not allowed to take up space, and once we do – even if it is to beg that people see us as human and stop killing us – we are infringing upon the privilege and ignorance of those who who wish to remain blissfully unsympathetic.

I responded that, if we had interrupted people’s brunches to perform a Valentine’s Day song rather than to protest police brutality, we would be entirely welcome. (Because Black people can entertain white people for centuries, but asking to be recognized as human is crossing the line!)

I responded that we have, in fact, tried all of the “peaceful” tactics he had suggested – only to have our flyers thrown away, our request to view videos of police executions denied, our humanity denied again and again.

The days of going up to someone with a gun and nicely asking them to sop murdering our people are over. There is nothing “peaceful” about the murders of Black and Brown people – and asking folks to “remain calm and civilize” is nothing but a justification for that violence.

2. ‘Protests Are an Inconvenience’

Those of us who participate in disruptive direct action tactics know that it will cause some level of inconvenience and discomfort. That’s the point of it.

Direct action in particular arises out of the frustration that nothing else will get the public’s attention.

The activists who were involved in the 1960s sit-ins were challenging “business as usual,” and were seen as outside agitators, inconveniences. For folks who have been receiving the benefits of white supremacy and racism their entire lives, being called out publicly should be an inconvenience.

But most of the angry people I come face-to-face with are not upset about police brutality, mass incarceration, or the Charleston Massacre. They are upset that they cannot take their normal route to work or get their caramel macchiatos on time.

In other words, they are being confronted with a reality they want to ignore.

These are folks that, when inconvenienced, not only make the extent of their frustration clear – they may also be violent and oppressive in their doing so. They have no other perspective than what their individual needs are in that moment.

There is a collapse of empathy in the people who spit at, yell at, and physically threaten people who are literally fighting for our right to live.

Further, there’s also a lot of privilege in the notion of being inconvenienced alone.

People of color are inconvenienced by white supremacy and institutionalized racism on a daily basis – we are denied equitable access to jobs, education, and healthcare; denied our humanity; constantly told we are less than.

It’s hard to breathe.

Being inconvenienced is one minor consequence in the struggle to eradicate oppression in the world. “Pardon the inconvenience: We are trying to change the world.”

3. ‘I Don’t Condone Violent Protest’

Without fail, protests and direct actions (whether they result in property damage or not) are almost always characterized as violent – but only when they involved Black and Brown people.

While I’ve yet to personally throw a brick through a window during any action, I have felt enraged enough to do so. And the fact that, in the moment I described earlier was among the first times I felt such rage, is a privilege – many of the folks in my community have personally known violence right outside of their doorsteps.

To condemn protestors (who destroy shit or not) as violent not only shows a lack of connection to their agony; it also shows me that folks don’t understand what violence is or isn’t.

Violence is the forcible tearing of a people from their homeland and benefiting off their forced labor for centuries. Violence is Dylan Roof. Violence makes murdered Black children suspect and their murderers innocent, or at worst, “troubled.” Violence has been used to colonize, enslave, sexualize, and destroy communities of color and other oppressed people for centuries.

Asking a people who have long been the targets of violence to “calm down and be peaceful” is oppressive and silencing.

Violence and property damage are not one in the same.

Being disheartened at the destruction of a community may be understandable to me, but having no sense of compassion for what may have led people to the point of that destruction is not.

The vast majority of people in the streets don’t have the sole mission of destroying things – we are here to demand change, to grieve, and to be seen.

When Pain Calls Us to Action: Direct Action in Many Forms

Reflecting on the memory still makes my chest hollow and my skin crawl, but the rage had been replaced with overwhelming sadness and helplessness.

On the night of the non-indictment of Darren Wilson in the murder of Michael Brown, I had just landed in St. Louis, MO to visit my father. We listened to the news on his car radio, he, bowing his head in defeated un-surprise, me, silently crying.

As we rolled up to the house and I saw my seven-year-old bother run excitedly to the window, my heart broke to know that he is less safe, that no precaution I could take would protect him. Later, my stepmom was careful to force a smile and to change the TV channel away from Ferguson on fire a few miles away whenever he entered the room.

These tragedies never stop being hurtful – but they also awake me more and more in each instance.

Because I know that this movement has only just begun. And taking up the streets in pain and protest is only one way of calling out oppression:

In my pain that night, I wrote a song for my brother and for all Black children. Others of us engage in online conversations that span borders and build up connections.

Many others are healing, teaching, and performing our ways to liberation. And many others are simply trying to exist in a society determined on our annihilation.

And each are direct action and protest in their own right.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Michal “MJ” Jones is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and is an awkward, Black, non-binary queer educator, activist, and musician writing to you from Oakland, CA. They earned their BA in Sociology from Sonoma State University, and went on to earn an MA in Student Development Administration from Seattle University and remain committed to improving access and retention to higher education. Listen to their music or read more of their work. Follow them on Twitter @JustSayMJ and read their Everyday Feminism articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more