A few weeks ago, a white woman came up to me as I walked through my city’s queer district.

She leered at me, barked “You’re hot” in my face, and reached out and roughly grabbed my breast.

Now, this wasn’t the first time a stranger had touched my chest in public without my consent. And so while I was hurt and disgusted, I wasn’t exactly massively surprised.

I shook the encounter off – feeling a little shaky and violated – and continued down the street.

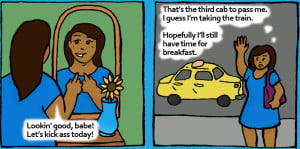

All of two damn minutes passed before a white man came up close, looked me up and down, snapped his fingers in a “Z” formation and said, “Damn, girrrrlfriend! Work it! You look fierce.”

On this particular day, I was makeup free, clad in my omnipresent black Doc Martens boots, and dressed in baggy overalls that make me look like a plumber who just got off shift. There was nothing fierce about it.

My two non-Black female friends who stood next to me, however, did look fierce – dressed and made up to the nines and resplendent in high heels. Yet, they went on unnoticed.

If these accounts seem gross – but totally unfamiliar – to you then my guess is that you might be white.

Because whether cognizant of it or not, those two white strangers participated in and perpetuated the phenomenon of what we call misogynoir – the first by treating my body like a sexual plaything she was entitled to, and the second by projecting his stereotypical and narrow view of Black womanhood onto me.

Misogynoir – a portmanteau that combines “misogyny” and the French word for black, “noir” – is a term coined by the queer Black feminist Moya Bailey to describe the particular racialized sexism that Black women face.

It’s a word used to acknowledge the very specific convergence of anti-Blackness and misogyny, and therefore is not applicable to non-Black women of color (or white women).

And it’s often overlooked in feminist discourse – because it disrupts the tendency that mainstream feminism has of universalizing womanhood as a uniformly shared experience based on the default narrative of white women.

Insisting that conversations around misogyny disregard race or take a “colorblind” approach are misguided and wrong-footed. Because only by accurately naming the nuances of oppressive behavior can we understand their origins and equip ourselves with the tools to bring them down.

That’s why discussing, recognizing, and understanding misogynoir is crucial to an effective and compassionate feminism.

So let’s start by understanding the following four tropes, pervasively woven into popular media, which contribute to making society a more hostile place for Black women.

1. The Sassy Black Woman

The Sassy Black Woman is a common stereotype that portrays us as one-dimensional sasspots who click our fingers and roll our necks and shout “Mmhmm!” at any given moment.

And while this may seem innocent (it’s just a joke, right?), the trope exists purely to demonstrate the supposed inherent comedy in female Blackness.

In and of itself, the SBW seems harmless enough, but this kind of lazy portrayal of Black women is not only insulting but contributes to a harmful cultural narrative which diminishes our multifacetedness.

It insinuates that we’re not much more than a few well-placed “Right on, sistahs” and “Oh no she didn’ts.” It relegates us to vacuous, predictable fluff. There is no complexity permitted to us – no humanity.

It’s that much easier to pass us over as prospective dates or for housing when you don’t see us as being on your emotional level.

The SBW trope leads to people thinking they can just snap their fingers and roll their necks – and suddenly they “get” what it’s like to be a Black woman, or that they can “bond” with us by parroting this parody of ourselves back at us.

Newsflash: You don’t, and you can’t.

When the white man I discussed at the start of this article clicked his fingers all up in my face, he made it very clear that he wasn’t seeing me as a person in my own right, but as a mirror for his own limited understanding of Black women’s nuance.

The SBW stereotype dehumanizes us by presenting us as cardboard cut-outs with no depth of feeling or emotion. It’s sickening and so pervasive that it’s contributing to a world in which white people literally cannot empathize with or recognize the pain of black people – because they’re so insidiously used to thinking of us in such simplistic and less than human terms.

White people need to accept the fact that we are not an endless ream of hilarity for them to giggle and gawp at. We are grown-ass women with every emotion under the sun, and we deserve to be seen as such.

2. The Hypersexual Jezebel

A common misogynoiristic stereotype of Black women is that we are inherently, permanently sexual, promiscuous Jezebels (named as such after a sinful Biblical queen).

White men often talk of their desire to fuck us because they’ve heard that we’re “freaky” and “up for anything” in bed – as if Black female sexuality is a monolith. I remember a white guy hitting on me at a club and him refusing to believe that I was turning him down.

“I know you want it, girls like you always do,” he sneered at me – and it’s not too hard to see what he was insinuating.

Bearing in mind that I’d already told him that I was so completely and utterly gay.

The idea that Black women are automatically sluts, whores, and hoes is prevalent (not to mention the sexist belief that women who have sex and are in the sex industry deserve to be judged and shamed). If you Google “black lesbian,” for instance, most of the results on the first page are explicitly sexual. If you just Google “lesbian,” though (which the white supremacy-led algorithm then assumes means “white”), the results are much cleaner.

Misogynoir is clear here: Blackness added to womanhood creates the expectation of rampant sexuality.

Black womanhood is painted as the opposite of the “purity” of white womanhood – and many pop stars, such as Lily Allen and Miley Cyrus, have used Black women’s bodies as props to “sex up” their images.

Presenting Black women’s bodies as the antithesis of the “innocence” of white womanhood marks Black womanhood as a signifier of guilt.

Our bodies are automatically tainted with an immovable sexual lens. Thus, often it is insinuated that any sexual abuse we face is our fault because, by virtue of being Black women, we were “asking for it.” This is the victim-blaming attitude of rape-culture and it is hurting us most.

While so many white women have found empowerment on Slut Walks for example, the same cannot always be said for the vast majority of Black women. What would it mean to call ourselves sluts when the world already takes that as a given?

Liberation does not look the same across all iterations of womanhood.

This trope robs us of freedom surrounding our approach to sex and sexuality. It silences and shames us.

It breeds toxic ‘respectability politics’, whereby we’re told by folks that if we are ‘good’ and do not engage in any kind of sex that isn’t strictly marital and procreative then we will be safe, and if we don’t dress a certain way we will be safe, and if we don’t date around then we will be safe.

That the only way we can actually achieve safety is if we just don’t leave the g-ddamn house – ignoring that no matter what we do, there will be someone who wants to hurt us and millions more who will find a way to justify that hurt.

The hypersexualization stereotype originates from the era of slavery.

In order for white men to justify their rape of enslaved Black women, they spread the idea that Black women were sexually insatiable. In this way, any instances of sexual assault were actually just “giving them what they wanted.”

We are relegated to animalistic and primitive by suggesting that we’re unable to exercise self-control, an excuse used to obfuscate the abuse done to us.

Stop using Black women’s bodies as a symbol of sex. Leave us to inhabit ourselves free from the smears of someone else’s sexuality. Learn to see our bodies as neutral, as our own, rather than dragging them down with the weight of your assumptions.

3. The Angry Black Woman

This trope plays on the idea that any discomfort expressed by a Black woman is unreasonable. Because something unreasonable is easily dismissed.

Our anger is seen as something that can be ignored – because it is not portrayed as stemming from a place of true grievance.

The Angry Black Woman stereotype paints us as irrationally mad – and is commonly trotted out to position us as the hysterical opposite to men’s (and especially white men’s) rationality.

The slew of scandalised white feminist think-pieces in the wake of Rihanna’s video for Bitch Better Have My Money reflects the discomfort that society has with the fury of Black women. White society is so used to downplaying female Black anger that the bold, unashamed and seething anger Rihanna displays in BBHMM just about caused mass panic.

Ask yourself why is there such uproar about the fictionalised violence of a Black woman, but a societal wide dearth of interest in tackling the very real violence that Black women face at the hands of white supremacy? Why is Black women’s anger seen as unacceptable but the conditions that create it are left to fester?

I have often been told that I’m “too aggressive” in my activism, especially by white feminists, even when I’m being decidedly placid and reasonable, proving how this trope plays out in real life, even in feminist circles. The prominence of the Angry Black Woman trope means that my actions are read as angry, even when they’re not.

It’s a tactic used in order to belittle our valid anger by portraying it as an inherent character flaw, rather than a justified reaction to circumstances.

4. The Strong Black Woman

The Strong Black Woman is a manifestation of misogynoir that shows up in places like the “Strong Independent Black Woman Who Don’t Need No Man” meme.

It’s a cultural narrative that positions Black women as able to withstand any and all emotional difficulty we face without any support.

Annalise Keating from How to Get Away with Murder is a perfect example of this. She is icy, impenetrable, and doesn’t let the trauma she endured in the past and present affect her at all.

She (ostensibly) effortlessly take down all obstacles in her path.

Annalise’s character is unerringly steadfast. When she cries, she immediately pulls herself together. When she’s in trouble, she does whatever she needs to do to save the situation, no matter how callous.

And while this may feel like a positive stereotype, as strength is a glorified quality in our society, the Strong Black Woman trope stems from the fact that Black women have been absorbing the brunt of physical and emotional labor for not only their families, but also for the white families they were owned or employed by for centuries.

It’s been preferable for people to see us as able to deal with anything and everything, because then we can be treated in deplorable ways.

This stereotype bars Black women from feeling as though they can healthily and wholly work through their issues. Instead, we must force them down and carry on in order to maintain a staunch and steadfast facade.

This trope also contributes to many Black women’s unwillingness to seek help for mental health issues and for us to be less likely believed when we do try and get help or discuss it.

***

Black womanhood is routinely and systematically devalued and dismissed in ways that white womanhood isn’t. And the above are just a few of the ways in which misogynoir shows itself in society.

The experience of existing at the intersection of Black and woman is a position that entails oppression from a variety of angles – and we have to be better at recognizing it, naming it, and calling it out for what it is.

The fight for women’s liberation must explicitly focus on eradicating racialized sexism if it’s ever to be effective and freeing for more than the privileged few.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kesiena Boom is a radical, Black feminist, lesbian writer based in Manchester, England. You can read her work on BuzzFeed, Autostraddle, and For Harriet. You can follow her on Twitter @KesienaBoom.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32