(Content warning: Intimate partner violence, physical assault)

I, too, have heard endless rumors that he’s been a bad date, and have heard stories of shadiness and strange behavior. […] I have heard about his ridiculous pick-up lines and have (to my shame) tittered about them with my friends […] Jian Ghomeshi is my friend, and Jian Ghomeshi beats women. How our friendship will continue remains to be seen.” —Musician Owen Pallett on Canadian broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi’s alleged assault of several women

In my second year of university, I learned what I had suspected for a while but refused to investigate: One of my close friends had been regularly beating up his boyfriend.

He knew that this was wrong, but he didn’t know how to stop – his boyfriend “was making him do it,” he said, by constantly flirting with other people and “acting slutty” in public. My friend’s defensive attitude overlay a deep insecurity: Thanks to long conversations and many nights spent texting, I knew that he often worried about being sexy or lovable enough for his partner.

And as much as I knew that I had to confront him, I also didn’t want to see him get in trouble or hurt. Not to mention the fact that I was completely in over my head and had absolutely zero idea what to do.

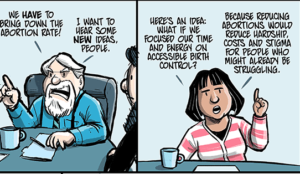

In marginalized communities, there are vast risks associated with “calling out” or naming abuse between ourselves. The reality is that there are already far too many racialized and queer and trans people imprisoned for life or killed by cops for (often unproven) allegations of crimes far smaller than abuse and assault. And men of color, in particular, are already stigmatized and stereotyped as being “savage,” brutal, and violent.

The external violence of an oppressive society makes any attempt to stand up to abuse inside our communities feel not only difficult and dangerous, but also treacherous – as though we are betraying our own. How many times have I heard that calling the police on their boyfriends is something that only rich, white cis women do?

Clearly, we have to find ways to tackle abuse on our own terms –in ways that combine both love and justice.

The following eleven steps form a strategy (which I encourage folks to adapt to their specific needs) for confronting a close friend who is abusing their romantic or sexual partner.I use it in both my personal life, and as a social worker with my clients. It’s divided into two halves: first, reacting to finding out that your friend is abusive; and second, what to do about it.

How to React to Finding Out Your Friend Is Abusing Their Partner

1. Acknowledge the Evidence and Believe the Survivor

Perhaps the hardest thing to do is admitting that someone we care for and trust is capable of hurting someone else. There’s the temptation to ignore the signs of intimate violence, or even deny outright someone’s assertion that our friend, or mentor, or elder, has been abusing them.

“I’ve known him for years, and he would never hurt anyone,” we want to say. Or “She’s been an amazing activist since forever, and she would never do anything like what you’re claiming.”

We struggle, naturally, to resist the possibility that the image we’ve constructed of someone we like or admire might be shattered.

But one of the most important things that contemporary feminism has taught us is that people don’t often lie about abuse – that we must learn to believe survivors, that anyone is capable of violence.

Let me repeat that: Regardless of how good or intelligent or well-intentioned they are, anyone is capable of violence.

2. Sit with Your Own Feelings

Part of the reason why abuse is so difficult to discuss is that it’s a massively emotionally charged topic.

Many of us also have personal histories around abuse and intimate partner violence. It’s enormously important to acknowledge our own feelings, memories, and biases as we move into any discussion of abuse happening around us.

So sit with your feelings: If you can, name them, one by one. Resist the urge to judge your emotions as positive or negative; try to allow yourself simply to have them.

Move through the whole cycle of denial, anger, bargaining, despair, acceptance, if you need to. There is real grief in losing the image of a “perfect” friend or acquaintance. Allow yourself room for grieving.

3. Talk to Someone About It

Abuse is most terrifying and overwhelming when we confront it alone.

This is true whether we’re experiencing or witnessing it. If you can, find someone to support you through the process of confronting your friend’s abuse.

Sometimes you may feel like it’s necessary to protect your friend’s safety or privacy while debriefing with someone else. Do you what you have to. This isn’t about gathering a mob to gang up on your friend’ it’s about making sure you have the emotional support you need.

4. Decide What You Want to Do Next

Review the options available, decide how you want to proceed, and make a strategy (see the list below for more on this).

Remember: You don’t have to do anything that you don’t feel safe doing or that might endanger someone else. Not doing anything, or waiting to do something, can be completely valid strategies in the right context.

Take your time. Work with your community behind and beside you. Love and accountability should be the basis of any action you take.

5. Remember What You Love About Your Friend

Your friend is still your friend, even after you discover that they’ve abused someone. The fact that they have hurt someone makes them human, not evil. They’re still your friend – the person who taught you to skateboard, bought you your first drink, stood up at your wedding, introduced you to feminism, or whatever else you treasure about them.

There is a tendency, after the phase of denial that someone in our communities might be abusive, to immediately reject the abusive person as despicable, unforgivable. You may indeed decide that you need to pause or end your friendship with them.

However, this is your choice to make. You are not obligated to stop caring about someone because they have been violent.

And to be totally honest, I very much believe that unconditional love is one of the most important supports in enabling abusive individuals to bring an end to the harm they’re causing.

How to Confront an Abusive Friend

1. Consult the Survivor

The most important aspect of any anti-abuse work, whether public or private, is to create space for survivors of abuse to empower themselves and make their own decisions.

More than therapists or social workers or activists, it is survivors who best understand the complexities and barriers of their relationships.

If you’re considering confronting a friend who’s abusing their partner, make sure that you contact the partner in question and get their consent whenever possible. They’ll be able to inform you about what’s appropriate, what would be helpful, and what might be dangerous for them.

Remember that it’s not your job to “rescue” anyone, but to help create options for them to choose from.

Starting the conversation with your friend’s partner can be awkward or difficult, but is often also extremely important – many survivors of abuse report wishing that someone had asked them if they were alright or if they needed help.

Conversation starters can be as simple and transparent as:

“Hey, how are you doing? I noticed that Aryn was pushing you at the party the other night, and I wanted to check in with you.”

“We don’t have to talk about this if you don’t want to, but I just wanted to ask how things are in your relationship with Logan. Tell me if this is none of my business, but it seems like he isn’t always the nicest to you.”

“I might be completely misreading this situation, but I felt like it might be important to ask you how things are going with Alisha.”

There’s always the possibility that your friend’s partner won’t want to have the conversation with you, and that is their right.

Even if the question upsets them, however, I believe that it is worth taking the risk of momentary discomfort in order to let someone know that you see what is going on and are willing to support them.

2. Consider Safety

No matter what the situation is, it’s always best practice to take a moment to think about safety: yours, your friend’s, and particularly your friend’s partner’s.

If you or the survivor of abuse believe that there is a risk of physical danger, then it might be important to postpone the confrontation with your friend or to make a safety plan first.

Safety plans vary, but usually include making sure that the person at risk has a place to stay, emergency money, and access to basic resources and human support.

3. Prepare Your Friend

“Surprise” confrontations and reality-TV style “interventions” that involve a lot of people and/or cameras usually go really, really, really badly.

Do not surprise or overwhelm (read: gang up on) your friend, no matter how good your intentions are. On the other hand, it may be a good idea to choose one other person who is close to both of you to accompany you through the conversation.

Let your friend know that that you want to talk to them about something important (or be even more explicit than that), and schedule a time and place that is comfortable for both of you.

4. Have the Conversation

Let’s just take a moment to acknowledge that telling your friend that you think that they’re abusing their partner is incredibly awkward, hard, and sad. There are few things I’ve done in my life that were harder. It’s possible that there is no “good” way.

Some suggestions I can make, however, include:

- Speak from a place of love. Explain that the reason you’re having this conversation is because you care about your friend.

- Own your words, feelings, and judgments. This often looks like using tentative phrases that begin with “I feel that,” “I could be wrong, but I think that,” “It seems to me like,” and so on. It also means not speaking for the survivor of abuse unless they’ve asked you to.

- Allow for pauses, gaps, and breaks in the conversation. Acknowledge that this is a dialogue that may have to take place over a few days, weeks, or even months.

- Resist the urge to give your friend orders or ultimatums. Phrases like “You need to do _____,” “If you don’t stop____, then_____,” and “You have to ____” aren’t helpful. Analyzing their behavior (“Maybe this is because of your past traumatic relationships”) is probably also not that helpful. Instead, point out the behavior that you see as abusive, tell them that you think it isn’t acceptable, and let them draw their own conclusions.

Examples of ways to state that you think your friend is acting abusively include:

“I wanted to talk to you because I’ve seen you push and slap your boyfriend a few times now, and it makes me worried about both of you.”

“I know this is awkward, but I have to tell you that I am worried about the way you fight with Sabina. You’ve told her that you’ll hurt yourself if she breaks up with you, and I don’t think that’s okay.”

One of the most powerful things we can do as friends is hold up a mirror to each others’ behaviors: We show each other what the things we do look like from the outside.

In many cases, this alone is enough to make a huge difference in ending abuse.

5. Follow Up

It’s hard to predict how the conversation will go.

If your friend refuses to acknowledge that they’re being abusive, then it may take a long time, and many more conversations (they don’t all have to be with you) to get the point across. It may become necessary to prioritize supporting their partner instead, whether that means offering emotional care and/or helping them leave the relationship if that’s what they want.

It’s equally likely, however, that your friend will appreciate your reaching out and might ask you to help them figure things out. Some things you can do in this case are helping connect them to local resources such as community organizations and mental health care. Often, creating support plans between informal networks of friends and acquaintances is also extremely helpful.

I believe that working with perpetrators of intimate abuse is actually very similar to supporting abuse survivors in that agency is key.

Most people who act abusively do so because they are feeling out of control in some part of their lives, and helping restore that sense of empowerment can make an enormous difference.

6. Love Yourself

I mean this in the active sense: Do things that are self-loving.

Anti-abuse work is hard, unglamorous, and usually goes unpaid. Confronting abusive friends can be emotionally destabilizing and draining. It forces you to re-evaluate everything you know about yourself, about relationships, and the people around you.

So ask for help. Feed yourself. Sleep. Drink water. Give yourself time to just rest and to feel.

And know that sometimes the hardest things you will ever do are also the most worthwhile.

Further Reading:

- The Revolution Starts at Home: Confronting Intimate Violence Within Activist Communities

- 10 Things I’ve Learned About Gaslighting As An Abuse Tactic

- Stop Asking Already: 6 Reasons Why Intimate Partner Violence Survivors Stay in Their Relationships

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kai Cheng Thom is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Chinese trans woman writer, poet, and performance artist based in Montreal. She also holds a Master’s degree in clinical social work, and is working toward creating accessible, politically conscious mental health care for marginalized youth in her community. You can find out more about her work on her website and at Monster Academy.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32