(Content Warning: sexual violence, physical violence)

Originally published on The Body is Not an Apology and republished here with their permission.

Well-intentioned people make mistakes – lots of them.

Mistakes must be expected and being held accountable has to be expected as well. The points below outline some of the common behaviors that show up often in social justice conversations.

I want to be clear that we all participate in some of the following counterproductive acts. We are not all privileged or all oppressed.

We are complex people with complex identities that intersect in complex ways. Therefore, we all show up in problematic ways with our privilege.

I own that my background is from the higher education setting, but I think the points below can be useful for all folks interested in creating dynamic change in the communities around them.

Moreover, this piece was written in the midst of the Michael Brown and Eric Garner non-indictments (many more people could be listed), so some of it may feel specific to race.

However, these rules apply beyond the identity of race; in fact, these rules only exist in the dynamic of intersections.

Below are ten counterproductive behaviors that people who want to do “good” commit and must actively work to correct.

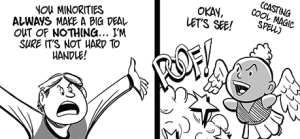

1. Being Quick to Marginalize Someone Else’s Experience

I was walking through a hotel lobby with colleagues. We were headed to a conference social, wearing business attire. There were quite a few conference attendees roaming around the lobby area at that time, all wearing business attire as well. It was a fairly loud, mingling setting.

An older white woman walked up to me and asked if I knew where she could get fresh towels. I was puzzled for a moment, which then indicated to the woman that I probably could not help her.

After the exchange, I looked at my friend in disbelief. Not utter disbelief or shock, because it was not my first time experiencing this marginalized view on the identities that I hold, but it did catch me off guard at my professional organization’s national conference — a place where we exchange ideas on how to better serve, educate, and develop the students that we work with.

I remember telling a few colleagues later at dinner and getting this response: “I’m sure she didn’t mean it like that.”

When someone shares an experience like this with you, please stop yourself from analyzing the situation. Listen, observe, connect with the emotion, and experience how real it is to the other person, which should in turn make it real to you.

No questions. Just listen and learn.

Hold onto your questions, which are the manifestation of your wanting the world to be a kind, good-hearted place. It’s because you see yourself in that older white woman. Get past that.

Be there for your friend, colleague, and mentor/mentee. And maybe ask questions later.

2. Choosing Not to Speak Up

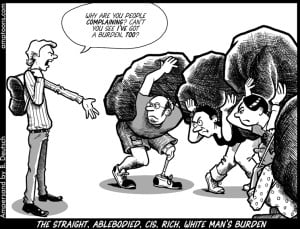

Your choosing not to speak up has either to do with the fear of your oppressed identity being pounced on or the presence of your privilege.

Regardless, too often, the courageous few are tasked alone with holding the integrity of inclusiveness in spaces. Too often, the oppressed have to make a dynamic choice to either speak or stay silent.

To stay silent comes with making peace with your inferiority to the dominant culture, self-hatred, and finding comfort in the status quo.

To speak is to risk not being a team player, being identified as overly sensitive, pulling the race/gender/orientation card, not being asked to Happy Hour, not being considered for promotion, and falling into a simplified caricature of one’s already watered-down self.

Do your work! Consider perspective as you enter and claim space. Pay attention, observe, and always consider that the ideas being explored in any space you enter are based on whiteness and a heteronormative, gender binary (specifically cis-male), abled-bodied, middle-upper class perspective.

Speak up.

Do not allow your colleagues and friends to take on the sole responsibility of shifting culture from “normal” to dynamic.

3. Responding Poorly When Held Accountable or Challenged

You are entitled to your feelings. Really, you are – and you are responsible for your self-development.

Here’s a secret: The oppressed often fear the response of the privileged around identity conflict. The oppressed often lose in these encounters and historically have lost their lives.

You often respond without thinking critically about the information or feedback being given because of your privilege and ego.

We all fall victim to this dynamic, generally around our salient identities. Acting purely out of emotion and in defense is not only dangerous to the livelihood of the oppressed, but directly conflicts with your goal of creating a more just and equitable world.

4. Not Taking the Time to Do Their Own Research (And Expecting the Oppressed to Educate)

There is nothing worse than identifying as oppressed and having to not only explain, but to also convince people that your oppression is valid.

Pick up a book! Google it. Read some Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, bell hooks, Janet Mock, Malala Yousafzai, and Gloria Anzaldua.

Do your work. Don’t expect all of your education to come from your Latinx friend, friend with a mental illness, or favorite trans personality or activist (Laverne Cox and Janet Mock).

Take a true interest in this crucial conversation, beyond when it is convenient for you.

This isn’t to say that you can never reach out to your “oppressed” relationships, but be prepared before you approach them. Be well read and make Google your friend.

It will make a world of difference to your friend that you took the time to educate yourself.

In the future, when you ask your friend questions, be prepared for a “no” or “not at this time.” The oppressed are continuously asked to defend their experience, so your question may be too much in that single moment.

5. Seeing Themselves as Either Good or Bad

We often will not fess up to marginalizing someone else’s identity or creating a space that is exclusive in nature.

For some reason, we have in our minds that if we take responsibility for this exclusion, then we’re admitting to being a bad person.

Instead, we must see ourselves as good people who will make mistakes. Good people create spaces of exclusion all the time. That is reality.

Even if the intent was good-hearted, the impact is what matters most.

Often, when challenged on their privilege, people love to default to their marginalized identities in hopes of subconsciously (or consciously) garnering sympathy.

Stop giving yourself limited choices once a mistake is made. Let go of not wanting to be seen as a “bad person.”

Take responsibility, apologize, learn, and do better in the future.

6. Executing Initiatives of Change without the Oppressed People at the Table

In the wake of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, Renisha McBride, and countless other deaths of black youth, we are seeing more and more rallies, protests, panels, and online activism by white people.

This is mostly done by well-intentioned white folks who are not inviting or trying hard enough to get black people at the planning table.

Generally, what we end up with is a poorly planned event that is offensive or exclusive to the people it was meant to serve.

I chose the recent scenarios as examples, since they are on the forefront of everyone’s mind.

This dynamic plays out with all other oppressed identities, which means that more of us than we would like to admit participate in poorly planned initiatives created from our privileged lens.

7. Creating ‘Mystical Negro’ [Or Insert Any Oppressed Group] Dynamics

This is similar to number four, “expect the oppressed to educate.”

However, for the well-intentioned and somewhat in-the-know group, this morphs into something a bit more intense.

You utilize your one friend as the absolute expert on said oppressed identity in addition to having them serve as your educator and moral compass.

The conversation around said identity becomes less about making systemic change or a space of support for the oppressed; instead, it moves towards helping the privileged figure out their lives around said identity.

In turn, the oppressed friend becomes mystical in nature, where their only purpose is to be there to help move you along in a morally correct life.

These folks have to carry your education and deal with their pain simultaneously. See number four as a way to improve this one-sided dangerous relationship.

8. Crying

Your tears take up too much space.

They very quickly turn the issue into an exchange about your feelings, your education, and making you feel comfortable in your privilege.

Politely tell your tears to have a seat. Several seats. A plethora, really.

When your tear glands start to well up, stop or get the hell up and excuse yourself. This is not saying that your tears or your hurt feelings do not matter; they just do not have space here.

Tears rarely worked for the oppressed in stopping the oppressor from beating them, selling them, lynching them, hanging them on a fence, dragging them behind their pick-up truck, shooting them outside their front doors in front of their families, publicly shaming them, and draining every ounce of worth from their souls.

So they do not serve any use here!

9. Giving Advice from a Place of Privilege

I heard Melissa Harris-Perry speak about this at a keynote, and it stuck with me.

I began to analyze the truth of it as it applies to me. I found that I indeed offer advice and solutions through my privileged lens. I moved with ease from conversation to conversation with friends, family, and students through my place of privilege.

This is something that we all do, mostly without being cognizant of the person and identities that sit in front of us.

Now we all can agree that the horrific abuse of Janay Rice was unacceptable and Ray Rice deserved to be held accountable for his actions.

However, we cannot make the leap that Janay’s only choice in this situation is to leave Ray. Her decision and our decision can be drastically different pending the intersecting identities that we hold.

To impose expectations on people through your experiences is to create exclusive and hostile environments that are potentially unsafe. It also places the people you are trying to help in a position to make decisions that are harmful to their interests.

When our privilege is involved, it’s quite difficult to name it.

I work at a university in support services with a multitude of students, and this scenario plays out all the time. I am often not conscious of the inappropriate and sometimes destructive advice I am giving.

A few examples:

- Advising a student to come out as queer to their family during the holiday break and to just be themselves. What privilege is blocking you from not considering that you cannot guarantee the student’s mental, emotional, financial, and physical well-being in this scenario?

- Advising a student to go to counseling and psychological services. What is the stigma of mental health in communities that they identify with? Do they have the money or insurance to pay for the ongoing treatment?

- Advising a student to get involved. Do they have the time? Are they working several jobs to pay tuition?

- Advising a student to study abroad. How will they pay for this? What does leaving their family look like?

We must interrogate our privilege to appropriately support the people in our lives.

10. Believing That Being Loving and Kind Are Enough

No matter how kind you are or how much of your heart you share with others, systematic oppression will still exist.

You cannot rest on being kind, encouraging, and loving. You have to commit yourself to learning more, becoming conscious of the system, and continually fighting for the cause of equity and justice, while allowing the oppressed to take the lead.

Stay away from comments and sentiments that ask for passivity and harmony; we are more concerned with equity and justice.

It’s easy to retweet or repost a social justice article on social media and stop there, but that doesn’t mean you are doing anything to end systematic oppression.

We have to move away from the niceties and do work.

Let’s break down do work.

It has already been explored beautifully by Franchesca Ramsey, so there is no need for me to find a creative way of saying the exact same thing.

I am asking well-intentioned people to do work, such as understand your privilege, listen and do your homework, speak up but not over, apologize when you make mistakes, and remember that being an ally is a verb.

Additionally, I have added a sixth point, courtesy of a good friend, which is that you do not have to be an expert. While all points are crucial, below are two points I want to explore further.

You do not have to be an expert.

Do not allow yourself to be immobilized by your lack of knowledge. You can still do something if you are willing to risk making mistakes.

In fact, you will never know it all. How could you? Your privilege will not allow you to take in the full experience of the oppressed. Move past your fear and engage other privileged folk around you and listen to the voices of the oppressed.

Ally is a verb.

You actually have to do something! Being an ally is not silently agreeing with the oppressed. You must constantly figure out ways to use your privilege to push forward the voice of the oppressed.

The work of an ally should not be an easy journey. You no longer have the luxury of silence. You should feel pain, uncertainty, fear, frustration, and exhaustion. It takes risking yourself, transparency with the oppressed, and calculated action to be an effective ally.

Please know that being active in equity work takes stamina, humility, courage, tough love, a strategic mind, and a forgiving heart.

This piece first appeared on Cody’s site, Consult Cody, and was reprinted on The Body is Not an Apology by permission.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Cody Charles serves as the Associate Director for Academic Enrichment in the Office of Multicultural Affairs at the University of Kansas. He is the author of Ten Counterproductive Behaviors of Social Justice Educators, Ten Counterproductive Behaviors of Well-Intentioned People, and Simple but not Easy: 25 Steps to Justice. Join him for more conversation on Twitter (@_codykeith_) and Facebook (Follow Cody Charles). Please email [email protected] if you have specific questions about his work.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more