This is a thought piece about poverty – but not in the way one might think.

It’s less about the causes and solutions, and more about using language to encourage personal accountability for our roles in either perpetuation or refusing to participate in the myths about poverty in the United States.

We know that people’s economic circumstances often dictate whether they’re viewed as successful in the US, or whether they are blamed for the country’s problems.

Language is part of how blame is passed, and as such, it’s important that our intentions to remedy the blame and lack of understanding about poverty include shifting our language around the term itself.

Personally, the term poor often reads to me like coded language for Black people, the same way that inner city, hood, ghetto, janky, and so on are all terms that can reinforce stereotypes that stem from a history of slavery, segregation, and unequal treatment under the law.

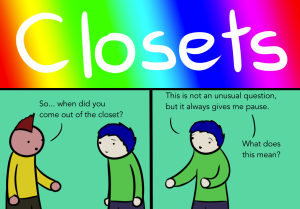

Language shifting – which is what we’re looking do here – starts with a question that seeks to address the most basic level of communication: What do you mean to say when you use the word(s) you use?

When we hear that someone is living in poverty, specific images may come to mind. But how does saying that someone is poor actually describe them? In other words, what does it say, or clarify, to define someone as poor?

When we use it to describe ourselves, the lens is ours to define. But it seems to me that when we’re writing or speaking about other people, it’s way too easy to generalize people and to perpetuate stereotypes when we use the term.

The problem with generalizing people as poor is that without distinguishing an individual’s particular experiences with poverty, we don’t get the full context of the person or their story.

That’s why I want to share some alternatives for generally labeling someone as poor. And I want those of us who write and speak as part of our living to reconsider using the general term poor.

Just as we are (painstakingly) slowly, but surely transitioning into a society where our language reflects people’s right to self-identify, we are also responsible for moving away from generalizations and over to context-focused and diverse representations of people and their situations.

How We Identify Our Environments – And Why It Matters

My mother and her siblings grew up in tenement housing around Kingston, Jamaica in the 1960s.

These makeshift apartment complexes were really single-family houses divided and rented out to families with low incomes. They shared bathrooms, kitchens, and general living spaces with multiple families, and the living conditions were inarguably subpar, including at times a lack of working indoor plumbing and proximity to potential environmental hazards.

Still, Mom always says that there were benefits to that way of life – access to intergenerational wisdom and help with childcare through other-mothering being two of the most important.

Benefits and caveats weighed and all, Mom and her siblings will tell you that, for sure, they grew up poor.

Fast-forward to the late ‘90s, when I was a sophomore in college, eating cornmeal porridge and Snickers bars for dinner because that combination was economically feasible and filled my belly. I had an old car I bought from an auction, and I lived in a lock your doors, fool neighborhood just north of Atlanta.

I kept a bus pass because my car was moody, and my meager refund checks from student loans served as a means of catching up on overdue bills and replacing rundown shoes. I was eligible for Food Stamps, and the only reason I never applied was foolish pride.

For sure, though, during that time in my life, I would tell you that I was poor.

Notice how those two examples of poverty – my mother’s and mine – differed?

I had my own apartment, and a car, and a bus pass, and I was in the middle of getting a college degree.

My mother’s parents were struggling to pay their children’s school fees and to keep them safe and fed.

Yet we both saw our circumstances as inarguable poverty, and in casual conversation, neither of us would be wrong.

But if I, as a professional writer, were to define myself as poor because of my specific experiences, I would be off – way off.

3 Alternatives to Blanket (Stereotypical) Terminology

If we endeavor to replace pervasive myths with inclusive language that encourages exploration and research over assumptions based on our own biases, then we have to look at context.

If we don’t, we risk sending our readers down a path of stereotypes about poor people, most of which are rooted in racist, classist assumptions that blame poor people for poverty, instead of looking at the impact of systemic causes and, eventually, solutions.

The US Census Bureau’s 2014 poverty line for a family of four was $23,850 in yearly income. Yet, one single person making that amount money may consider himself or herself poor.

Would that person be wrong?

Let’s look at some varied examples of poverty, so we can use language that speaks specifically to a person’s environment, and not to the stereotype about what that person may or may not be experiencing.

A. Generational Poverty

This refers to an ongoing situation where children are born into households with significant economic lack and never transition out of that situation.

In this household, children’s parents are faced with a combination of financial, educational, and social resources that make it increasingly difficult for members of that household to earn more money and change their environment.

Income and achievement are directly linked and evident in everyday experiences, not just for major life goals like going to college or buying a house.

One household can look like grandparents living in a home they own, with their children and grandchildren. Some work sporadically – as seasonal construction workers, for example. Others diligently work in jobs that yield enough to pay for food, a portion of utilities, and daily living expenses like bus passes, clothes, toiletries, movie tickets, class field trips, and mobile phone service.

In yet another household, an eight-year-old child may not eat breakfast at home because there isn’t enough food, and may be performing at a lower level than her classmates – not because of ability, but because of other relevant circumstances, such as hunger and family issues, on her mind.

In any of those instances, lack of resources isn’t based on a temporary setback or an easily identifiable trigger. Generational poverty is longstanding and ongoing – and no one-event solution (except perhaps winning the lottery) would immediately resolve the issues at hand.

B. Financial Shortfall Poverty

This one is also referred to as “situational poverty” and is usually a result of a major (and often unexpected) life shift, such as a mother getting suddenly laid off from her job, which cuts the family income down by 70%. Or a father is diagnosed with an illness that requires expensive medical treatments not covered by his insurance.

These are usually surmountable with time, meaning that Mother eventually finds a new job or Father gets approved for supplemental insurance program to cover his medical bills.

This is the transitional nature of poverty that individuals and families have long faced. We can be poor at one stage in our lives, and we can transition from that stage in the space of a year.

Financial shortfall poverty has a single trigger – an identifiable life event or maybe a series of them – that led to the financial shortfall.

Solutions are often feasible and become easier to attain over time.

Financial shortfall poverty has a clear catalyst and oftentimes, a clearly identifiable solution.

C. Short-Term Environmental Poverty

This one would refer to the “college poverty” I addressed earlier. Ramen noodles and Dollar Store snacks abound because you’re living in a no-frills space with the intention of transitioning (post-college) into a higher economic status.

You can even come from a middle-class family and end up short-term environmentally poor. If you’re a student at an expensive college where your tuition isn’t fully covered by scholarships and loans, you could be college poor.

You have very little money for food and rent. You may live with multiple roommates and eat for convenience and cost instead of physical and mental wellness.

But here, you’re clear that it’s short-term.

You’ll graduate and you’ll have a job, or get one soon. With short-term environmental poverty, you willingly participate in this tough, but temporary poverty.

You see it as a means to a greater goal, and you have the option of choosing to work more jobs, or leave school, to change your financial situation.

Why We Need to Let People Name Themselves

Self-identification is important, especially among marginalized people.

For many, poor is something to avoid or to overcome, but it is also not a badge of dishonor.

In other words, just as my mother mentioned the benefits of her childhood living environment, and just as I learned many vital life skills during my experiences with poverty, other people see value in their situations, too.

A strong sense of community, a deep understanding of perseverance and tenacity, and the ability to be authentically optimistic in the face of pervasive adversity are some of the characteristics that come to mind when I think about what it means to live in, and to survive, poverty in the US.

Of course, I don’t only consider the useful life skills that can come from economic hardship, whether short-term or longstanding. Poverty, in all its forms, is complex and deeply varied. It has negatively impacted many people’s lives in various forms, sometimes fatally.

It’s important that as the tellers of the stories, writers, and speakers embody a sense of personal accountability for steering our readers and listeners away from generalizations about what are deeply varied situations.

This means we qualify what we mean when we say “poor.”

This means we make great effort to be thorough and specific when we talk about a person’s economic situation.

This means we say “generational poverty,” for example, when that’s what we mean, so that the people we’re discussing are explained in a bit of context, instead of lumped into an overarching category that may not be either descriptive or even respectful, depending on the details.

With respect for self-identification and a strong sense of responsibility for inclusive, context-focused language, we can shift our society away from harmful myths and ambiguous descriptions over to informative, thought-provoking discourse.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Akilah S. Richards is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a six-time author, digital content writer, and lifestyle coach who writes passionately about self-expression, womanhood, modern feminism, location independence and the unschooling lifestyle. Connect with Akilah on Instagram, Tumblr, or her #radicalselfie e-home, radicalselfie.com. Read her articles.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more