“If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. If you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” —Lilla Watson, Australian Aboriginal activist

A few years ago, I attended a workshop facilitated by Peggy McIntosh at the annual White Privilege Conference. In the workshop, McIntosh explained that she wished she could go back and rewrite the introduction of “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” her seminal piece on White privilege.

The problem, she explained, is that people tend to treat her piece as a checklist of privileges that every White person experiences – but it’s not. The piece describes the context of her White privilege as a White woman with wealth privilege in an institution of higher education.

But privilege doesn’t function as a monolith; White privilege isn’t the same for every White individual and doesn’t function in the same way, to the same degree, for all White people.

However, all White people experience racial privilege. Full stop.

Our privileges, though, are complicated by other aspects of our identity that intersect with our Whiteness.

Intersectionality is a complex idea, but part of it means that when we are discussing someone’s class or ableist oppression, we must consider those things in the context of other areas where they might be marginalized as well as where they might be privileged.

Almost forty years ago, Derrick Bell wrote of the “interest convergence dilemma,” whereby institutional change toward ending racial oppression doesn’t often take place until White people see it in their best interest despite the incredible work of activists of Color.

As a White activist who sees the liberation of those I love, as well as my own liberation, as tied up in realizing intersectional racial justice, what Bell’s work says to me is that I have a responsibility to find new ways of engaging White people, of helping White people understand our own interests in realizing racial justice and in divesting from Whiteness.

And that’s the idea of collective liberation! Everyone with privilege has a choice to divest from systems of privilege and to join movements led by oppressed and marginalized people.

When those movements are intersectional, then working in concert with others means that we are also working for our own liberation.

So toward that end, I want to complicate some of the items from McIntosh’s list, highlighting how those items exist at intersections of identity that mean different things to different White people.

Hopefully this can help us break through some of the defensiveness that comes up in conversations about privilege. Namely, when White folks deflect to aspects of our identity that are marginalized rather than being accountable to our privilege.

Before proceeding, though, I want to briefly note the irony of White people (myself and McIntosh) being centered in conversations about the privileges that are the result of oppression.

If we as White people listened to people of Color, articles like this one simply wouldn’t be necessary. Unfortunately, though, often we as White folks aren’t the best at listening to people of Color, but maybe we will hear things differently from a fellow White person.

Thus, if you’re White, I can’t stress enough how important it is for us to diversify our media consumption to learn from people of Color. But if it helps you to hear me complicate our conversation about privilege, then I hope it inspires you to continue along the path toward more anti-racist ways of being.

1. ‘If I Move, I Can Find Housing in an Area I Can Afford and Want to Live In’

For most White people, this is likely true. After all, Whiteness as a system has long ensured White people had greater access to wealth and rarely faced red lining or other forms of racist housing discrimination.

But the ability to rent or purchase housing one can afford where one wants to live is most definitely a marker not just of race, but of class – and not all White people have the same access to capital.

Unfortunately, what this often means is that low-wealth White people use their class struggles to avoid acknowledging racial privilege.

Yet, the reality is that White poverty and Black, Brown, Asian, or Indigenous poverty are not simply different degrees – they are wholly different kinds of poverty because of how Whiteness affords access.

White people may face stigma and lower levels of access for being poor. But we also are less likely to worry about intensive police surveillance and violence. And we are likely to have more structures of support when things get tough.

For many White people, we may be able to buy or rent in areas where we feel centered and where White wealth is accumulated. However, to speak about wealth as a White monolith doesn’t actually serve us in engaging White people in working for racial justice; some White folks frankly don’t feel very privileged as a result of their economic struggles.

Because to be White and wealthy in the US is simply not the same thing as to be White and poor.

As a result, we have a responsibility to talk about the access to wealth that we are afforded and that people of Color simply are not, but we need to do so in a way that describes the complexity of that wealth.

We can’t compare the ways that Whiteness operates for wealthy White folks to low-wealth White people, but we ought to still recognize how White privilege is at play.

After all, when poor White people commit crimes, they definitely may be locked up, but they also are likely to get better treatment by police and the courts than people of Color.

I mean, when two low-wealth moms (one White and one Black) broke the law for the sake of their children, the White woman was showered with Christmas gifts by police while the Black woman received jail time, community service, and a $30,000 fine.

To complicate the connection between Whiteness and wealth doesn’t let White people off the hook for our privileges; rather, doing so better engages White people, which is a profoundly anti-racist act because it exposes the connection between violent capitalism and the lie that is Whiteness.

2. ‘My Children Will Be Given Curricular Materials That Testify the Existence of Their Race’

Let’s be honest: Standard curriculum is essentially “Whiteness Studies.” White people are most definitely going to see themselves and their identity positively represented in their curriculum along lines of race.

But for some White students, they’re not able to recognize how their racial identity is centered when other aspects of their identity are attacked and erased.

When our curricula don’t show complex portraits of gender, sexual identity, and class, it hurts students – not just White kids.

Just last year, I spoke at a high school, and in my talk, I mentioned the violence that Trans and Gender Non-Conforming people face in the United States face, noting in my comments that Trans women of Color are more likely to experience violence than any other segment of our population.

After the talk, a young person who I read as White came up to thank me, identifying themselves as Trans, telling me that this was the very first time in their entire education that anyone in school acknowledged the existence of their identity.

Frankly, this statement broke my heart. That this young person could go through sixteen or seventeen years of schooling and never see a vital aspect of their identity mentioned would likely make it pretty difficult to focus on the real and important ways that their racial identity is centered in their education.

To a White Transgender student, the fact that their Whiteness is privileged may very well be real but it might not feel so important when they face real and rhetorical violence in school every day.

Thus, to engage that White student in working against oppression means complicating our narratives about Whiteness and education to speak to intersections.

It’s not likely to resonate with a Gay or Trans White 14-year-old to explain how they are centered in their curriculum if we are not also able to address how they do face so much daily verbal and physical assault for being who they are, including from teachers, while also discussing how Queer people of Color face higher rates of violence and harassment.

To be White and Gay or Trans is to have a different relationship to Whiteness than to be Straight and Cis and White, and we have to address Whiteness as complicated by our identities.

So to engage race in education, we must also address all of the other forms of marginalization and oppression that students face, particularly in a society where those most at risk for violence are those living at the intersections of multiple erasures: Queer and Trans people of Color.

3. ‘I Can Often Arrange to Protect My Children from People Who Might Not Like Them’

When I reread this particular item from McIntosh’s list, I can’t help but think that this is a privilege for very few people.

Parents of LGBTQAI+ children surely can’t assure that their children are protected from hostile teachers, students, or community members.

And again, LGBTQAI+ youth of Color don’t have the same levels of protections that many White students have, but to pretend that White students who exist at the marginalized intersections of gender and sexual identity can rely solely on Whiteness to protect them from harm does nothing to actually understand or address White privilege or oppression.

The same can be said of children with disabilities, as regardless of a child’s racial identity, they face violence from teachers and other students. Children with disabilities are universally more likely to be sexually assaulted and abused than students without disabilities. To be clear, students of Color with disabilities face increased levels of incarceration and harsh discipline that White students do not face.

The point, though, is that Whiteness cannot universally protect students from those who wish to do them harm.

And this is to say nothing of the more systemic forms of oppression that Queer people and people with Disabilities experience across racial identities.

Aside from analysis of Whiteness, what of children without citizenship documentation? Of Muslim or Sikh or Jewish children of any racial identity?

Absolutely, Whiteness and its connections to wealth buys protection from harm in ways that are simply not afforded to any people of Color, but honestly, this seems like a privilege that just isn’t afforded to very many people.

And to talk about Whiteness in monoliths doesn’t actually help us address the ways that race intersects with marginalized aspects of people’s identities.

Tunnel Vision Is Not a Privilege

I could likely do this with every one of the items in McIntosh’s list, but you get the point. McIntosh’s work is important, as it has helped countless White people, including myself, to think more critically about the benefits afforded to us because of our skin color’s place in a system of oppression.

And in all of the above instances, White people surely can and do experience very real and powerful racial privileges, but if we aren’t willing to talk about those privileges at the intersections, then I fear we do little to actually engage every possible White person in working for racial justice.

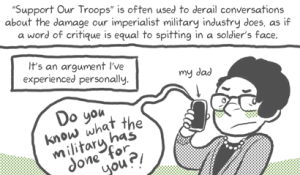

No, we shouldn’t need to contextualize our privilege every time we are forced to confront it – to do so can be a way of avoiding accountability.

But as White folks working to engage other White people, contextualizing privilege can go a long way toward realizing true accountability, where we are not simply engaging out of paternalism but out of our own need for intersectional liberation.

So to close, I want to highlight just one more of the items from McIntosh’s list, one that definitely is a privilege in one way of thinking, but more broadly, it is not a privilege:

“My culture gives me little fear about ignoring the perspectives and powers of people of other races.”

This is absolutely true; as a White person I can never consider the lived reality of anyone who isn’t White, and this ignorance can be seen as a privilege.

But is it one? Because frankly that “privilege” sure does feel like a terrible detriment.

When I live in the tunnel vision that Whiteness affords me, I don’t live an engaged life, one that is enriched by the hard work of building relationships across difference and the challenges and triumphs that come with working in coalition to realize justice.

And in thinking about the terrible way to live that’s reflected in this statement, I can’t help but think the isolation inherent in Whiteness is a part of every single privilege we reap by investing in that system.

And this is why we must complicate how we as White people talk to other White people about privilege: Doing so opens the door to new ways of thinking about why we must end our addiction to the privileges Whiteness affords.

Rather than simply working from paternalism, we can understand how our liberation is “bound up with” the liberation of people of Color.

And that’s the genesis of true solidarity.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Jamie Utt is the Founder and Director of Education at CivilSchools, a comprehensive bullying prevention program, a diversity and inclusion consultant, and sexual violence prevention educator based in Tucson, AZ. He is currently working toward his PhD in Teaching, Learning, and Sociocultural Studies at the University of Arizona with research interests in the role that White teacher’s racial identity plays in their teaching practice. Learn more about his work at hiswebsite here and follow him on Twitter @utt_jamie. Read his articles here and book him for speaking engagements.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32