We’ve all heard it before.

“We’ll it’s a stereotype because it’s true!”

But actually, stereotypes aren’t true, your brain is actually tricking you. I trusted you, brain!

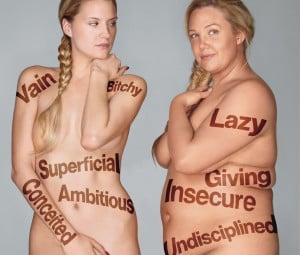

What exactly is a stereotype? Well, it’s a simplified generalization that’s used to describe an entire group of people. Stereotypes can be both negative, like white people can’t dance, and positive, black people can dance. Either way, stereotypes do the same thing: They lump together instead of seeing them as individuals.

“Wait, you’re black, so of course you can dance.”

I mean, I can do a mean two step, but besides that, I wouldn’t say I’m a great dancer, but most people think that “black people can dance” stereotype is true because of social conditioning and the media.

Eddie Murphy’s Raw came out in 1987, and then, his famous “white people can’t dance” joke was repeated all throughout the 90s. We had movies like Save the Last Dance, where a white girl learned to dance from a black guy. Bring It On also perpetuated the stereotype with rival black and white cheerleading squads. That’s just the tip of the iceberg.

How does a joke from a popular stand up routine transform into a stereotype? Well, it’s been discovered that your brain doesn’t have the cognitive ability to discern TV from reality, especially when it’s developing. Twenty years later, when BuzzFeed writes articles like, “17 Ways White People Dance,” you now think, “Yeah, white people can’t dance, and black people can.” You’ve been conditioned.

“Okay, but if I’m at a party, and I absolutely have to choose, I’m going to pick the black guy over the white guy because they just have better rhythm.”

Now you’ve gone beyond generalization, and into bias. Stereotypes are cognitive shortcuts. Your brain wants to make an immediate judgement about somebody based on their gender, race, or age. You might think this is harmless, but when you apply a stereotype behind that impulse, you are biased.

Let’s break it down. If you see an Asian person and think, “Yeah, they must be smart,” you’re stereotyping because your brain has been trained to associate Asians with intelligence. It all goes back to conditioning. The Asian kid in The Goonies was literally named Data. Harold in Harold and Kumar, George Long in Law and Order, Christina Yang in Grey’s Anatomy – the list of Asian film and TV nerds goes on, and on, and on.

But if you hire an Asian person for a job over someone else just because you think Asians are smarter, that’s bias. You’re applying a stereotype to an individual without actually considering the individual.

“Okay… But! This stereotype is true. I mean, statistically, Asians outperform everyone in education, and you cannot argue with numbers.”

Here’s where things get a little complicated. There’s a social psychology phenomenon called stereotype threat, and it’s kind of a double edged sword. When you hear you’re not supposed to be good at something, you tend to underperform, often unconsciously.

In 1995, several experiments showed that black college students performed worst on standardized tests compared to white students when they were confronted by racial stereotypes. When these stereotypes weren’t emphasized, black students did just as well, and even better than their white classmates.

Unfortunately, studies in the past twenty years showed that the stereotype threat phenomenon is only getting worse.

When it comes to Asian American students, many say they feel pressured to live up to the smart Asian stereotype. According to a recent sociology study, “The Asian American Achievement Paradox,” they’re not imagining this pressure.

The study found that teachers and guidance counselors often assumed their Asian students were smarter, putting them in advanced classes that they didn’t ask for. Some Asian students even admitted to getting better grades than they thought they deserved. Basically, stereotypes can become self-fulfilling prophecies.

“Wait, you just admitted that stereotypes are true! I knew it!”

Sure, Asian Americans often get good grades, but does that mean that socially awkward Asian nerds stereotype is true? No, absolutely not. The scientific community calls a fact about a large group of people an empirical generalization.

Here’s another example. Men are taller than women – empirical generalization. Statistically, men are taller than women. But in reality, there are some women who are taller than men.

On its own, “men are taller than women” is pretty harmless. But unfortunately, society then created stereotypes around this generalization.

The idea of a short man overcompensating, or that women don’t like short men are stereotypes. They simply don’t apply to everyone.

But because of stereotype threat, women are conditioned into this feeling. It’s not uncommon to hear “I’m just not into short guys,” and maybe short guys feel the brunt of this and feel like they have to go the extra mile on dates. Thus, the stereotype perpetuates itself.

But we have the power to differentiate between an empirical observation and a stereotype. And stereotypes are constantly changing, so we should stop thinking about them as shorthand for the truth.

Look, stereotypes seemed convenient, and actually, our brains want to stereotype. It’s easy to look at someone and assume things about them as a group, but your first instincts aren’t always right.

In reality, we should give people a chance to be themselves, instead of unfairly labeling them.

So have you ever experience stereotype threat, or maybe you changed your mind about a stereotype? Tell us in the comments, and we’ll see you next week, right here on Decoded.