A person sitting against a tree looks concerned as they rest their head on their fist. Source: iStock

When I was in middle school, my family started going to an autism support group. Well, I say “family,” but in reality, my sister Creigh was going for her high school volunteer hours and kept dragging my mother and me along.

Creigh seemed to think that, because she was my sibling and I’m Autistic, it was her responsibility to show support for me and other autistic people by going to these meetings and guilting my mother and me into going, too.

She never asked me – she simply assumed, as so many do, that it was something I would want. Creigh has apologized since, of course, but the damage had still been done.

You see, the autism support group was ironically not a place friendly to autistic people. In fact, it was one of the environments most toxic to an actually autistic person that I have ever been in.

It wasn’t that they didn’t care. They were all loving parents of autistic children, trying to do what they thought best for them. But the things they said about autistic people, while I and another autistic adult were sitting right there in the room, were absolutely ableist and generally terrible to hear.

I was told, repeatedly, that I was an inspiration. They talked about what a terrible burden having an autistic child was. They brainstormed seemingly infinite ways to cure autistic people like me, never mind asking if we even wanted a cure.

These parents talked about ways to train their children to be normal, talked about how stressful it was knowing, as they thought they did, that if they even slipped up once on reinforcements and punishments, we, their children, would slip back into our old autistic ways.

These are just a sampling of the things they said.

You’re a middle schooler, sitting there, hearing how much having you around is hard for your family and how wrong being autistic – something you consider to be part of your identity, which you couldn’t change even if you wanted to (which you don’t) – or expressing any hint of this part of your identity is.

How would you feel?

The answer, by the way, is absolutely terrible.

What’s worse, you don’t just get these sorts of messages one night a month at a support group. You receive them everywhere.

On the television, from your support workers, from your doctors, from your classmates, even in innocent Google searches related to your disability.

There is no escape. Even adulthood and the self-advocacy abilities that, at least for me, have come with it, are no protection.

This is my life.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

You see, the people who say these things (which you may well be, without knowing it) don’t mean to be hurtful. In fact, they tend to be those most trying to be helpful. Which means that if we can just spread the message of what sorts of things not to say, there’s a fair chance they might actually change.

So here are the sorts of things that I, and other disabled people, are often told that are quite ableist and hurtful.

1. “You Should Be Grateful For Your Caregiver.”

Should I be grateful for someone acting like a decent human being just because I’m disabled?

It’s not like the caregiver gets nothing out of this – whether it be money or cuddles, whatever it is, surely they think it’s worth it. To assume that my disability automatically makes me such a burden that I should be grateful to anyone who cares for me is very hurtful.

This message, like so many others, implies that my worth as a human being is next to none, simply because I’m disabled.

It’s not.

2. “You’re So Inspirational!”

Why am I inspirational for living?

Because that’s what you’re unintentionally saying.

You’re saying that just by living my life – basically not committing suicide – I’m somehow an inspiration. As though being disabled is so bad that it’s miraculous I haven’t killed myself, that I can do anything at all.

It’s not that bad.

And by telling me that, you’re accidentally sending me some really negative messages about what you think about my life.

3. “You Don’t Look Disabled…”

Invisible disabilities – like arthritis, mental illness, and chronic pain – may not be able to be seen, but they can have every bit the same impact as a visible disability.

If you’re saying this, it means the person you’re talking to already has an invisible disability. They don’t need you to diminish its existence by linking it to what they look like. Those of us with invisible disabilities need you to be our ally, not another person who puts us down.

4. “Oh, So You Don’t Have a Real Disability.”

A disability is a disability is a disability. This isn’t a competition.

And yet people with invisible disabilities, particularly neurological differences, are often viewed as not “truly” disabled.

But a disability such as depression can be every bit as much a disability, if in a different way, as something which can be physically seen. All disabilities are real disabilities.

5. “Stop Complaining – Other People Have It Worse.”

Just because there are things that are worse doesn’t mean that other people don’t have it bad.

Moreover, by saying this, you’re making me feel ashamed of how I feel about my disability. And that hurts.

6. “You’re Not Like My Child, So You Can’t Talk to Me About Your Disability.”

When people say this to me, what they mean is “even though you have the same disability as my child, since I perceive that it impacts you differently than my child, I don’t have to listen to you and your needs.”

But here’s the thing: You’re also not like your child, and I’m a lot closer to understanding what it’s like to have their disability.

So either both of us need to stop talking, or you should listen to what I and other disabled people are saying.

7. “You’re a Burden on Your Caregiver/Society.”

This is Creigh here.

Due to Caley’s dysgraphia, for the rest of this article we’ve done some fusion, a la Steven Universe, and written from Caley’s perspective, me simply taking her words and expanding them with her permission. But talking about this one was amplifying her depression and anxiety so badly that she asked me to take over altogether.

I think that is a lesson in of itself.

Because this is a message Caley has had drilled into her so much from — well — everyone, to the extent that the mere mention of it is enough to bring up so much anxiety and depression for her that she literally cannot talk about it.

And when I say literally, I mean it. When this subject was initially brought up, she was rendered temporarily non-speaking (as happens to autistic people under lots of stress).

I think it’s clear just from that how incredibly hurtful this message is. Please, please don’t spread this pain any further. Because the fact that my sister literally cannot even talk about this without pain is messed up.

Now, back to the rest of Caley’s words.

8. “If You Just Tried Harder, You’d Get Better.”

I am trying.

At least, I’m trying to get better from my severe depression and anxiety – autism, as I mentioned, isn’t something I need to get better from. But it’s not like there’s a magic cure for depression and anxiety.

I’ve tried light therapy, talk therapy, countless medications, supplements, even simply “pushing through” the terror and darkness that accompany my disabilities.

But none of these have swept my disabilities away.

And honestly, I’m not sure if any of them ever will.

Saying crap like this to me, or telling me that if I “just tried ____,” I would be cured (and implying that it’s my fault for not trying it) is absolutely messed up and is only going to make me feel worse.

9. “Isn’t It Nice – She’s Willing to Be Friends with You!”

Being friends with me isn’t an act of charity. (And if it is, you’re not an actual friend.) It’s just — you know — friendship.

And yet being friends with disabled people is held out like an act of heroism.

Do you know what that’s telling me? It’s saying that my worth is so low that you’ll literally put someone on national television just for being my supposed friend. That’s just wrong.

10. “Hey, I Raised Awareness/Money For Your Condition On Your Behalf!”

I prefer acceptance and understanding over awareness or money towards a cure.

Many people are aware of most disabilities. Or if they aren’t, they can Google.

On top of that, I don’t want a cure for some of my disabilities. But accepting this part of who I am and understanding how to accommodate me is infinitely harder to find.

What’s more, you probably didn’t engage a disabled person in this advocacy you were doing. Instead, driven by the best of intentions, you likely just charged right in and assumed you knew what I and others with disabilities wanted.

Great motivation – and I’m happy that you care – but if you’re not working with us in advocacy and following our lead, you’re not doing your best as an ally.

11. “You’ll Never Be Able to _______!”

Let me tell you all the things people have told me I couldn’t do.

They said I’d never go to a typical school, never read, never write, never be able to take an advanced class, never go to college, never graduate college, never live on my own, never be able to get along with a roommate.

These weren’t just teachers or administrators saying these sorts of things. These were family members who loved me, professionals who were paid to evaluate my abilities, and classmates who supposedly knew me.

Let me tell you which of these things they were right about. Oh, that’s right. None. I have done every single one of those things.

Don’t ever tell someone they’ll never be able to do something because of their disability. Not only will you look foolish if they prove you wrong, but you’ll also be hurting them in the process.

12. “We Need to Find a Cure for You.”

I don’t actually want a cure for being autistic. My condition is part of me, and if I didn’t have it, I wouldn’t be me.

Opinions vary depending on the person and the disability in question, though. For instance, my depression is also disabling, and that I definitely want a cure for.

The point here is that you need to see what the community of people with a given disability (not to be mistaken with their parents) seems to want on the whole before you go campaigning for a cure for it.

People with some types of disabilities (particularly degenerative deadly disorders) want a cure, yes. But not all groups feel the same way, and you can’t assume.

13. “You’re No Fun – You Never Come and Do Things with Us!”

Because of the way my disabilities affect me, I can’t participate in activities the same way others do. I just can’t.

But if you come to me and ask me about a way to hang out that I can access, then we can do fun things together.

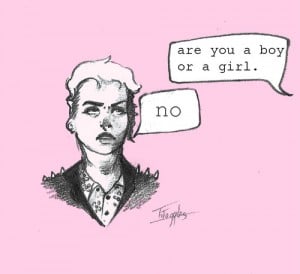

14. “Try to Act More Normal.”

Why?

To say this is to imply there’s something wrong with the way I am. But there really isn’t.

So I flap my hands sometimes and wear earplugs in restaurants. So what? There’s nothing wrong with being different.

15. “You Mean You’re a Person with a Disability, Not a Disabled Person.”

I prefer to say I’m a disabled person. But more than that, I’d prefer you not overwrite my own voice.

Some people like person-first speech, but I prefer identity-first language, which recognizes the role disability plays in my identity. And it’s incredibly rude to think that you get to be the one who decides how I get to talk about myself.

I’m not telling you how to talk about who you are – show me the same courtesy.

***

It’s not easy being disabled in our society. But hearing these sorts of hurtful statements on a daily basis makes it even more difficult. Please contribute to the solution – just don’t say them at all.

We are in desperate need of actual allies for disabled people like me here in the world. But actual allies don’t say this kind of messed up nonsense – and if they have, they apologize and learn from their mistake.

This article is meant to help you do exactly that. Learn from your mistakes, if you’ve ever said one of these unintentionally hurtful statements. Listen to us, the disabled people you’re trying to help. And follow our lead.

We have amazing advocates blazing a trail already – what we need you to do is stand in solidarity with us.

There are wonderful disability allies who give me hope for the world. By reading this article, you’re on your way to becoming another one of them. Will you join us?

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Caley Farinas is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s a recent graduate with a Bachelor’s in Public Health who writes about the effect society has on the “disabled.” Caley writes from her experience as an Autistic woman with dysgraphia and anxiety disorders. Because of these disabilities, it is hard for her to write and she gets assistance from her sister Creigh in writing/typing. That said, any words that you see attributed to her are her own, and she edits and approves anything her sister Creigh types. You can see more of Caley and Creigh’s writing on their website Autism Spectrum Explained and their Facebook page.

Creigh Farinas is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s a graduate student pursuing a Master’s degree in Speech Language Pathology and who already has a B.A. in Psychology and a post-baccalaureate in Communication Sciences and Disorders. Creigh is still learning more every day, and her sister Caley reads, edits, and approves everything that Creigh writes about disabilities. You can see more of Creigh and Caley’s writing at Autism Spectrum Explained.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more