“…but seriously, you can’t trust Muslims,” a family friend told me a few weeks ago.

“Wait, what?” I asked, wondering how a seemingly innocent conversation about baseball had taken such a horrible turn.

“They’re all terrorists,” he said.

I paused….I’d been down this road before.

I imagined what would happen if I contradicted him again. He’d tell me how he’d read about the Qur’an on the Internet and that he “knows” that Islam is a “religion of violence.” He’d cite right wing news outlets and politicians who espouse Islamophobic perspectives.

And he’d dismiss my counter-arguments as symptomatic of the “political correctness” that has supposedly weakened American culture.

Did I have the energy to call him out for the umpteenth time?

I wish that I could say that it was some abstract sense of social justice that ultimately motivated me to speak up. But it wasn’t.

Instead, I imagined what kind of ally I was (not) being to the people I love and care about by staying silent.

I imagined some of my students. The fiancé of one of my best friends. Most of my interlocutors in West Africa.

How would the many Muslims in my life respond to this family friend’s dangerous rhetoric?

And what would they think if they knew that I had permitted it to continue unchecked? Especially because, as a non-Muslim in an Islamophobic society, I am in the privileged position to speak out without (for the most part) fearing for my safety.

So I took a deep breath, moved my gaze from my toes to his eyes, and started in.

Both before and after the recent terrorist attack in Brussels, presidential candidates, congresspersons and parliamentarians from the from all around the world have spread toxic Islamophobic messages, often while inciting violence against Muslims.

And irresponsible journalists the world over have broadcasted such hate speech, directly and indirectly validating both the politicians and their oppressive values. Perhaps even more problematically, because of the widespread circulation of these messages on traditional and social media, they have also permeated everyday discourses.

It’s not “just” bigoted, attention- and power-seeking politicians and pundits who spread ignorance and hate regarding Islam and Muslim communities. Now it’s also some of our friends, our family members, our neighbors, our teachers and our co-workers.

Fortunately, bluster aside, most social justice-minded folks recognize the dangers of such speech. We know that it inaccurately represents Islam and perpetuates the oppression of and sometimes even violence against Muslim individuals and communities. We know that we need to respond.

Yet, we are often reluctant to do so. Why?

1) We Are Taught to Be Scared to Contradict Islamophobia

Physical and verbal attacks against those perceived to be Muslim have been on the rise over the past decade:

- Christian priests have staged dramatic book burnings of the Qur’an.

- Presidential candidates have called for the torture and carpet-bombing of Muslim families, as well as the establishment of squads to “patrol and secure” Muslim communities in the United States.

- Right-wing nationalists in France set fire to a refugee camp housing Syrian Sudanese refugees.

- Police and security officials have disproportionately surveyed and detained Muslims.

- Islamophobic groups and individuals have vandalized mosques and assaulted Muslims.

Even non-Muslim people of African, Arab and South Asian descent have been targeted because attackers have mistaken their names or appearance – i.e., skin color, turban, beard, headscarf, and so on – as “Islamic.”

Racist and neo-facist groups have also attacked social justice activists who denounce Islamophobia.

Despite these non-Muslim aggressors being tyrannical and violent, often the discourse behind such attacks maintains that it is against supposedly dangerous Muslims that Euro-American societies must “defend” themselves.

Ironically, such exclusionary attitudes paint Islam – and thus Muslims – as contrary to such “Western” values as democracy and tolerance (which, given North America, Europe and Australasia’s long history of colonialism, slavery and kyriarchal oppression, is a dubious claim).

The message, therefore, is that Islam is the “enemy,” incompatible with Euro-American belonging. Under a faulty you’re-either-with-us-or-you’re-against-us logic, therefore, defending Islam positions us with this so-called enemy.

This is scary because such an affiliation, so we are taught, also opens us up to physical and verbal attacks.

2) We Perceive Those Who Express Islamophobia As Ideologically Rigid

If someone deems physical or verbal abuse as a legitimate expression of Islamophobia, their narrow beliefs are likely too solidified to be substantially altered.

And even if one does not espouse such abuse, most of us have likely encountered our share of people who regardless of our efforts, and regardless of the strength of the evidence in our toolkits, refuse to budge from their anti-Muslim positions.

Media outlets – from hostile comments sections to videos of certain political rallies’ explicitly racist participants – likely contribute to the perception that all who espouse Islamophobia are ideologically immobile.

Not everyone is a closed-minded brick wall, though.

Not everyone who makes Islamophobic comments is resistant to alternative perspectives.

For many, Islamophobia remains unconscious and internalized, a product of Euro-American society’s pervading white and Christian supremacy.

Challenging this de facto position can open some to reconsider their anti-Muslim sentiments and why they have maintained them in the first place.

3) We Don’t Feel Equipped to Speak Up

As non-Muslims ourselves, we often don’t feel adequately equipped to confront Islamophobia.

Sometimes, those who make anti-Muslim accusations justify their positions through (often problematically) citing the Qur’an, quoting an Islamic individual or group antagonistic to non-Muslim and/or Euro-American societies, or referencing social or political relations within Muslim-majority regions.

How, though, do we address Islamophobia if we are not experts in Islam?

How do we reference religion or politics without speaking over or misrepresenting Muslim communities?

Due to an unfamiliarity with Islamic theology, for example, non-Muslim allies might feel uncomfortable or reluctant engaging such rhetoric. However, we must also consider the consequences of silence.

If we do not counter anti-Muslim accusations, we risk implying that such accusations are valid and acceptable.

We risk perpetuating – and even augmenting – pervasive Islamophobia.

Strategies for Speaking Up

1) Be Safe

One cannot and should not attempt to engage in change-making dialogue if they do not first feel safe in their surroundings.

Islamophobia is about power: it is intended to reproduce white and Christian privilege while silencing people and discourses that contradict the bases of that privilege.

So, if you perceive the other person(s) or setting as threatening, your intervention can wait.

Or, if for whatever reason you cannot emotionally address an anti-Muslim statement in a given moment, that’s fine too. Self-care is important, valid and radical!

Most important is for you to feel physically and emotionally secure.

How else can you effectively tackle the complexities of Islamophobia?

2) Do Your Research

Without suggesting that we should all become experts in Islam and the politics of Muslim societies, it’s best to have at least a basic familiarity.

So, try to learn about Islam and Muslim communities if you can, and not just from popular media sources, which often reproduce problematic analyses.

Consider reading the Qur’an or commentaries about religious texts. There’s also a wealth of amazing Islamic and/or Muslim-authored fiction, poetry, history, philosophy and political science. Watch some films coming out of the Muslim world (Egypt, Iran, Indonesia and so on have long cinematic histories).

Listen to the music produced by Muslim artists the world over (you’ll likely recognize certain melodies, styles and instruments that have been incorporated into more Euro-American genres).

In my experience, many folks attempt to justify Islamophobia through a limited understanding of Muslim politics or scripture. For example, they’ll quote a Qur’anic verse (often found online) that seemingly justifies their prejudiced opinion.

But just like reading a few chapters (or even the entirety) of the Bible does not make one a Christian scholar, neither does a selective reading of the Qur’an make one an expert of Islam.

One cannot only cite one or two decontextualized Qur’anic verses in order to prove an Islamic point. Indeed, a handful of phrases from anything fails to capture the spirit of the text, let alone an entire faith.

Of course, the same logic also applies to non-Muslim allies. However, learning a little about Islam and Muslim societies isn’t about claiming to be specialists.

Rather, doing your research will help you to shut down some of the problematic arguments that you might encounter. It will also help you to feel more comfortable and confident engaging Islamophobic statements.

3) Cultivate Friendships with Muslims

Maintaining relationships with people different than oneself is vital for practicing strong, well-informed allyship.

Such friendships and networks help to build solidarity with and be held accountable by Muslim communities.

Substantial engagement with Muslims also helps allies to better understand some of the intricacies of Islam and the diversity of the Muslim world. This includes further empathizing with the everyday struggles that many Muslims experience in the face of oppressive Islamophobia.

Consequently, the insight that these interpersonal connections provide serve to destabilize biased, uninformed anti-Muslim messages.

4) Address White and Christian Privilege

Islamophobia is just one of many oppressive expressions of white and Christian supremecy. Exploiting a politics of fear, Islamophobia serves to marginalize a supposedly well-defined group (Muslims) while simultaneously privileging white, Christian communities.

Islamophobic rhetoric generally works in two ways. First, it reproduces a disingenuous narrative that claims that Muslim communities are violent, repressive, zealous, anti-American/European and anti-Christian. It falsely suggests that Muslims are the exclusive perpetrators of terrorism.

At the same time, this rhetoric represents white folks, Euro-Americans and Christians as the level-headed, non-violent victims of “jihad.”

This creates a dangerous double-standard by which Muslims (as well as non-Muslim People of Color) become suspicious for engaging some of the same practices – such as regularly attending places of worship, celebrating religious holidays, studying holy texts, going on pilgrimages and so on – as their white, Christian counterparts.

Therefore, when countering anti-Muslim accusations, we must address this flip side of the coin.

- Why is the label “terrorist” only applied to Muslim and Arab, South Asian or African perpetrators?

- Why are white Christians who commit acts of terrorism problematically labeled “mentally disturbed” (and thus, somehow not held responsible for their actions)?

- Why do we limit our analyses of terrorism to religion – specifically Islam – rather than also considering the roles of whiteness and toxic masculinity?

- Why don’t we acknowledge that Muslims are the primary victims of terrorism (not only of radical “Islamic” organizations, but also of USA-led drone strikes, black sites, Guantanamo Bay and so on)?

***

As allies, it is not our responsibility to speak for or over Muslim individuals.

Indeed, we must give platforms to Muslims to speak for themselves.

At the same time, however, non-Muslims must also address the Islamophobia being reproduced within our own communities.

As uncomfortable as it might be, we need to call out explicit bigotry and call in those who articulate internalized anti-Muslim sentiments, even when this means confronting our family and friends.

How else can we address Islamophobia, particularly if those persons making anti-Muslim accusations have limited exposure to Islam and/or their Muslim peers legitimately fear challenging those making oppressive comments?

Just as it is white folks’ obligation to confront anti-Black racism within white communities, it is non-Muslim folks’ obligation to confront Islamophobia within non-Muslim communities.

That is why I decided to address my family friend’s problematic comment. Which is not to say that this single conversation completely re-oriented his perception of the world.

Not surprisingly, he could not convince me to fear Muslims. Nor could I convince him that his fears were misguided and founded in white and Christian supremacy and a history of American imperialism.

But, I still consider the conversation a victory, but not only because I challenged his narrow beliefs when it was clear that few had.

This was also a small victory because others around us were listening, nodding in approval as I constructed my argument.

Those listening learned that Islamophobia is dangerous and oppressive. And they learned that they can, and should, take a stand against it.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

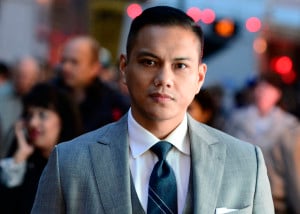

Andrew Hernández is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is a public anthropologist and teacher, completing his PhD in cultural anthropology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Andrew bases his research out of West Africa and the Sahara, working on issues of human rights, crisis and religion. A former adjunct lecturer, he is now a Professional Teaching Fellow at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. You can follow him on Twitter @AndrewHernann or at his website www.AndrewHernann.com.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32