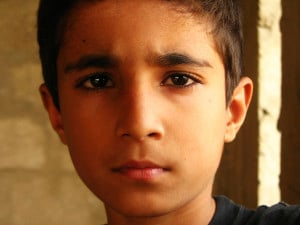

Source: iStock

For most of my childhood, I thought there was something wrong with me.

I would see other children, my peers, living life, playing sports, drawing, creating, and smiling — and I’d always felt as though I was living some lesser form of life than them.

Unlike those kids, I only mustered smiles when I was uncomfortable, when I felt I had to, or when someone praised me. My life felt like a movie on a small TV with a gray-ish tint and grainy audio, playing right next to an HD, surround-sound theater screen.

I constantly wondered why. Why I had this unshakable feeling that life was water slipping between the cracks of my fingers; why everyone around me could hold their water, still and unmoving, with confident hands.

I overflowed with panic nearly every waking moment thinking that today would be just another day that I would waste more life.

I couldn’t find help because I didn’t know how to ask, but when the products of my struggle escaped my lips or empowered a disagreeable action, I was typically told I was “dramatic.”

Growing up, I didn’t know what anxiety or depression were.

I didn’t know that what I was feeling had a name or that other people felt that way too. I’d accepted that I was defective and that those who called me dramatic were simply brave enough to tell me the truth.

I was trapped in this dichotomy in which I was both plagued by thoughts and feelings I couldn’t hope to stop or control, and haunted by the idea that it was somehow all my fault.

Needless to say, I was on my own when it came to my demons. No one was helping me, so I’d just smile and pretend I was okay — at least no one called me dramatic when I pretended.

I lived a childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood ripe with overpowering anxiety, but truly believed the problem was myself. I thought I was weak.

From what I could tell, there weren’t any other boys going through what I was going through.

I didn’t see boys on TV or boys at my school talking about their feelings. I didn’t see these boys admitting they were afraid, talking about how they felt, or crying outside of physical pain or sports game losses.

I was told I was a boy, and to act like one, so what choice did I have?

I didn’t understand how I felt and because no one gave me the recognition and validation I so desperately needed, I began to feel like my pain wasn’t real; I thought that because it was in my head, it didn’t matter.

I wasn’t bruised or injured, and beyond physical pain I wasn’t really taught how to cope except for “dealing with it” and “being tough,” both of which are ultimately nothing more than vague and dismissive.

I assumed physical pain was the only real pain and that everything else was meaningless.

Little did I know, the mental and the emotional could be equally as painful, or more, than the physical.

Although I was raised as a boy, I did not grow up to be a man. I found my connection to the female spirit within, and have found peace in a bigender existence wherein I am comfortable with the coexistence of my male sex and female gender.

Despite the (many) challenges that come with this identity, it hasn’t been entirely bad. For one, I am finally living as a more fully realized version of myself. No longer do I feel like I have to play boy to keep the aggressive forces of this world from focusing their spotlight on the naked, trembling self I harbor within.

But even more, I was able to explore the depths of my mind, heart, and spirit that I hadn’t felt I had permission to before. For the first time, I was walking my full truth, and part of that was the reality that I was struggling with anxiety and depression.

Little boys are so pressured to perform an archaic and violent archetype of masculinity, to be strong containers of patriarchy, that there is never space examine what that expectation does to them. To heal from the toxic. To even recognize the toxic.

Here are 3 ways mental health support was denied to me because of my perceived boyhood.

1. Counseling Was Never Presented to Me As An Option

I’d never seen or heard of other boys getting counseling support. I was worried that if I was to be treated, I’d be labelled a weirdo by my friends and family and would be treated as “delicate.”

I didn’t want to perceived as fragile, and counseling was something that I was told was for sensitive people. My grandfather always said that issues should be handled within the family or not talked about at all. I believed the only way I could be an authentic boy was to handle everything on my own.

I wanted to be the romantic, brooding sort of boy who was deep and had problems but never asked for help.

I also knew I was already feminine. I knew I was different and that I didn’t necessarily express myself the way other boys were. It wasn’t intentional; I couldn’t stop my hips from swishing or my voice from being so high-pitched and soft.

So, I didn’t need one more thing making me different from other boys. In fact, it was the last thing I wanted as a kid.

The first time I even saw a counselor was in college. I went for a multitude of reasons, but the gender demographics of my school was one factor that helped me immensely when it was time to take that step towards healing. My school was almost 70% female-identified people, and so at school I felt almost safe from the powerful gaze that keeps its eyes on boys to make sure they’re acting like “real men.”

I finally felt safe from toxic masculinity, and as if the “boy police” I’d feared all my life were far, far away.

For the first time ever, there was a space between the pressures of being a boy and myself. It gave me the opportunity to spread my wings and break a taboo, which in this case, was attending counseling (or even just considering it)!

And I could finally do so without shame or fear of judgment because the young women and female-identifying people on my campus had no interest in enforcing male values on me.

It also didn’t hurt that the counseling was free.

Once I began attending, I felt myself coming alive. For the first time in possibly ever, I felt like there was someone I could talk to who actually didn’t mine listen to me talk as much as I wanted.

I didn’t feel like I had to bottle anything up, or lie, or pretend.

I remember one of my first meetings with my counselor, I came into the office silent, overwhelmed by feelings of want and being lost. She waited patiently for me, giving me time to breathe, and finally, without warning, I began to cry.

Male socialization taught me never to cry, but if I did there’d better have been a tangible reason for it. In that moment, however, I was able to cry because I was simply sad and overwhelmed. There was no specific reason, I just felt like crying.

It was one of the most liberating moments of my life.

Counseling helped me to recognize my anxiety and depression, mostly because I was permitted to talk about how I felt, out loud, long enough to figure it out. I wasn’t shirked off as society tends to do with boys and their feelings.

My feelings were validated and celebrated, in appropriate cases. Through my sessions, I was essentially letting my counselor get to know me, and in letting them get to know me I got to know myself.

2. I Was Taught to Be Strong, and That Being Strong Meant Not Asking For Help

This is probably a bit obvious, given the context of the post, but it’s a big deal, because it’s going to be difficult, if not impossible, to get help if you’re unable to ask for it. What this means is that by default I was unlikely to get help because not only was I not taught how to ask for it, but I was actively discouraged from asking.

I was told that you have to be self-sufficient, that men are providers not receivers. I was required to get through any obstacle without any allies or assistance, and be better for any of the difficulties I faced.

If I couldn’t do these two things, I would be estranged from manhood and, consequently, from a society that still identifies people through a very limited binary — and at the time, that was the only society I knew.

I felt like I would lose part of my identity and float somewhere in identity purgatory.

I encountered this problem when I started my first job as a bus boy at a sports bar. It was loud, crowded, and there was always someone yelling at you to do something.

The masculinity of the space was overpowering and I often felt like the space itself wished for me to leave. I remember being worn down, at my end, but being unsure of how to talk to my boss about how I was feeling.

What I needed at the time was a day or two to breathe and find some peace between my schedule, college, and a tumultuous relationship. But I couldn’t come up with the words that I thought would convince my boss that I deserved a break. I wasn’t in any physical pain and I had no proof that I was struggling.

I thought I would probably look like a crybaby and would convince them that I was less capable than my more masculine, physically fit male co-workers.

I didn’t know how to ask for help, so I didn’t, and only two or three weeks later my hours were severely cut because my performance had slipped. I tried to let them know that I wasn’t feeling quite myself lately, but it was shrugged off and my boss went back to eating his dinner as if I hadn’t said anything at all, as if I was nothing at all.

I was being punished, socially, in front of my co-workers, for asking for help. There are only a few moments in my life when I felt smaller than I did then.

I put in my two weeks shortly after — as was likely intended.

More and more I found that asking for help left me vulnerable and weak. It didn’t feel worth it anymore. I’d rather fake and try to be a man and at least be left alone, than put myself out there and get stomped on.

The latter was painful AND embarrassing. At least the former was just painful.

I probably would’ve struggled a lot less during college if I’d had that job… but I just got so lost in the chaos and had no way of navigating my way to safety.

3. I Was Never Taught To Grieve Or Express Pain

I’ll never forget when my first dog Pepper, a German Shepard-Husky mix and runt of her litter, was nearing the end. She was throwing up a lot and seemed to have lost most of her energy. I lived with my grandmother and grandfather at the time, along with my twin brother, and little sister.

One night my grandfather came to my brother and I and said that if Pepper didn’t make it through the night that we had to be strong for my grandmom and sister. I felt shocked, offended, and horrified.

Before that moment I hadn’t realized that even a death didn’t qualify as enough to cry for.

If I couldn’t grieve death, what was I allowed to grieve? What pain was valid? And what did it say about me given that I felt so much.

The suggestion burned a fire in me and made tears well up in my eyes. Even as a kid I knew my grandfather didn’t intend to harm me; in fact, he probably thought he was doing the right thing in a world that would demand that I be “a boy.”

***

The world pushes boys, men, and folks who identify with masculinity into harmful, oppressive boxes within which they cannot feel, express, love, grow, or care in all the ways that they might want to.

We need to send boys, men, and those aforementioned folks that it’s okay.

It’s okay to grieve. It’s okay to cry. It’s okay to ask for help.

It’s okay to be vulnerable and it’s okay to let other people be your rock. It’s okay to love without reservation and it’s okay to feel whatever it is that you’re feeling.

You’re human, you’re not a machine. You have a heart, not a set of batteries and instructions. Your life is yours, and no one else’s.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Jayson Flores is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and the founder and editor of Gay on a Budget, a punk, emotional, intersectional blog with a little bit of sass. They’re working on their fiction in hopes of becoming the next J.K. Rowling, and their real-world writing in hopes of becoming the next Tavi Gevinson. Jayson can be found on Tumblr, and be contacted at [email protected] or on Twitter @gayonabudget.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more