I’m writing this piece anonymously because my mother frequently Googles me – types my name into a search bar to find all I’ve been up to splashed across her screen. I think she does this just so she can send my articles to her coworkers to show them how proud of me she is.

I’m writing this anonymously because sometimes, in an article, I’ll reference something she said to me, shining onto her supposedly banal words a light bright enough to prove how harmful they were.

I deconstruct her. And it makes her sad.

I’m writing this anonymously because I don’t want to hurt my mother – not now, not ever. Because I know, without a doubt, despite her faults, that my mother loves me deeply and completely, that she always tried her best to protect and to save me.

Ditto, truth be told, about my father. But he doesn’t Google me. I’m not really sure he truly understands how to use a computer.

My dad still uses AOL, y’all.

My point is: This is not actually an article about my parents.

Because for any buried emotions about my parents and my childhood that do spring up for me, I have a therapist. This is not an article about my parents, no matter how easily they – and you, my reader – might twist it into one.

This, instead, is an article about you and about me and about the legacies that we pass on. This is an article about our culture.

This is an article about a culture that doesn’t respect women’s boundaries, a culture that can’t take “no” for an answer, a culture that buries women’s sexuality in guilt and shame. This is about a culture that, imperceptibly, seeps its values into the minds and hearts of well-meaning parents until that culture’s most awful beliefs about women come flying out of the mouths of the ones that love us most.

This is an article about rape culture – and about how my parents taught it to me throughout my entire life, never knowing its toxicity. Because when you’ve been taught your whole life to ingest poison, how would you know not to feed it to your kids?

This is an article about that.

Because I think that we, as feminists, do an amazing job of talking about the relationship between parenting, rape culture, and consent culture – but mostly in abstract terms. We say “Here’s how to do better” much more than we say “Here’s how we fucked up,” almost as if we’re detached from it, as if we’re not swimming in it, as if we’ve evolved out of it.

But I can’t detach myself from rape culture.

I can’t detach myself from the knot in my stomach that forms when “no” is sitting in my throat and letting it out means risking its being ignored.

I can’t detach myself from still, years after I’ve begun unlearning all of this bullshit, feeling gaslit in my own body: Is that really what I want? Do I really know what’s best for me?

Because I learned those lessons young. And I learned them across the span of my entire life. And I want to be honest about what that looks like.

And this is what it looks like when parents who love you still don’t always know how to love you, especially when you’re growing up girl in a culture that normalizes and excuses rape.

This is three examples of how my parents – entirely inadvertently, never having known the danger – taught me that my consent and my autonomy didn’t matter, shaping me well into adulthood.

Lesson #1. Three Years Old: ‘You’re Not Allowed to Say No’

I have a cousin named Angelo who was born exactly 32 days before me. My mother and his mother – sisters – were pregnant with what would become their firstborn children at the same time.

Angelo and I would start kindergarten together, holding hands as we walked to school, our mothers trailing behind us. And because Angelo lived one floor above us in our apartment complex, we spent many afternoons combining My Little Ponies and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles into an early-90s mythical dream world.

Everyone in our families – and especially our mothers – thought we were a-dor-a-ble. And I guess we were: him, with his chocolate drop eyes and bottom lip stuck out in a perpetual pout; me, with a head full of raven ringlets and a propensity for emphatically talking with my hands.

They loved us – both individually and as a pair.

And so, whenever it was time to leave one another, they, innocently enough, would say, “Angelo, give Sophia a kiss!” And my mood would immediately dampen.

Because I hated when Angelo would give me a kiss. With the fire of a thousand suns, I hated it.

That cute little pout that everyone loved on him was always shining with drool. He’d always kiss me with a wet smack that made me grimace, and so I tried to get out of it whenever I could.

Sometimes, that meant attempting to avoid the situation altogether (which is kind of hard when you’re a baby and can’t just be like, “OH. Look at the time! Gotta run!”). Sometimes, that meant ignoring their requests or walking away from them. Sometimes, that meant outright saying “no.”

And each protest would end in the same way: “Awww, come on, Sophia, give Angelo a kiss!” And then they would erupt in cheers when, knowing I had no other options, I suffered through it.

And this behavior – this forcing of children to be physically intimate with people in their families, despite their own discomforts – is so common that I can already imagine people reading this and rolling their eyes at my insistence that this perpetuates rape culture.

But I learned early on that my refusal would be met with insistence, and that the only way out of it was to close my eyes and acquiesce.

So when your baby tells you no, or otherwise indicates a discomfort with or avoidance of a particular person or situation, trust that they know themselves better than you do – and remember that their bodies belong to them, and only them, even when they’re so small.

Lesson #2. Ten Years Old: ‘Boys Will Be Boys’

Growing up, my mom’s side of the family had a summer home on a lake in Vermont. The sunshine yellow cabin sat situated among tall pines that dripped earthy-smelling sap onto our picnic table – and sometimes our heads.

We, a bunch of city kids, spent our summers trying to catch frogs with our bare hands and pretending we were 19th century explorers as we canoed across the pond.

But because the house was owned, equally, between my mother and her three siblings, that meant we would often share the amenities on any given weekend in July.

We were there together a lot: my immediate family, along with whoever else was visiting at the same time. And I had two cousins – Sonny and Joey – who were notorious for causing trouble.

Whether it was creeping into the neighbor’s yard to steal time on his hammock, jokingly pushing one another around our late-night bonfires, or (literally, y’all) almost setting the entire house aflame once, these boys were fun, but they were troublemakers.

And one of their favorite pastimes was pulling at the bathing suits of my older cousin, Theresa, and me.

Under water, they would swim by us and tug at the bottoms of our bikinis, trying to jokingly rip them off. Sometimes, they would even dig up globs of sand and muck from the bottom of the lake to splat against our backs, cold and sticky between our skin and our suits.

For one thing, the latter was just disgusting; my bathing suits all ended up with stains in them from the thick mud. But the former was more terrifying.

It wasn’t just a game of “How gross can we, as eleven-year-old boys, be?” (which is bad enough), but one in which girls’ bodies were specifically and routinely identified as objects of play – especially if they were naked.

My parents had taught me, growing up, never to let anyone touch me “where your bathing suit covers” – and here were my cousins, pulling at those layers of protection, trying to take them off.

Our parents sat on the beach, dripping in vaguely coconut-scented tanning oil, in lawn chairs the whole time – watching on, lest we drown.

I felt awful about the way that I was being treated. I was embarrassed, and I felt violated. Surely, I thought, that if the behavior were wrong, someone would say something.

But even when I called “Mom!” or “Dad!” for help, the response I was met with was along the lines of a half-hearted “Leave the girls alone.”

In conversations later, when I got older, I found out the truth: that my parents felt powerless against the parenting of others.

If my parents ever protested, asking Sonny and Joey’s parents to discipline their children, they always shrugged and sighed, “They’re just playing. Boys will be boys.”

And instead of taking matters into their own hands – talking to me privately about this issue, yanking me out of the water and into safety, refusing to share lake time with those family members – they let it slide, too crushed by the social graces around allowing parents to make their own decisions about their children.

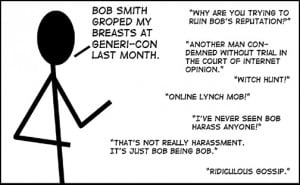

We allow young men so much freedom to be menacing, and then we refuse to take community responsibility for their actions when they violate another person. That’s what they were trained to do, after all.

And those who want to protect and rally around the survivor are left powerless against the communal agreement that a slap on the wrist is enough of a punishment.

So what I learned from those early interactions was that when I needed help, I wouldn’t get it. What I learned was to just let the cold, wet muck smack against my back – and then be the one responsible for washing it out after, without any retribution or restoration.

Lesson #3. Fourteen Years Old: ‘This Is What It Means to Be a Girl’

I credit my middle school best friend with teaching me about feminism, even if I don’t remember her ever using the word. She was simply the first woman I knew who was brazen, who wasn’t afraid to say (or shout), “No. That’s bullshit.”

We became friends in the sixth grade because, individually, we were misfits, and we realized that together, we could at least be misfits with friends. Claire sat next to me in computer class, and I liked that she kind of talked to herself while she played. And she didn’t mind that the only thing I knew how to talk about with fascination and authority was Olympic figure skating.

There was a lot that I learned from her – that I could mix patterns, that I could dye my hair blue, that I could listen to Nsync and Radiohead, that I didn’t have to believe in God.

But most of all, she taught me that when grown men whispered perverse things in my pubescent ear, that I could talk back.

The first time I heard her do it was when we were twelve – the year that we became friends. Street harassment was relatively new to me then, something I’d only been experiencing for about a year.

When it comes to fight, flight, or freeze, I’m a hardcore freezer. I dissociate from violating environments and experiences, and then try to distract myself later to forget it.

And that’s how I’d respond to street harassment. Unsuspectingly, I’d hear words like “pussy,” “fuck,” and “horny” whispered into my ear, and I’d just freeze up. Walk away. Never say a word.

But Claire? We were walking down the block one day when, all of a sudden, I saw her turn around and shout, “What, are you a child molester? You like little girls? Huh?”

I knew, immediately, why she’d said what she said, and I grabbed her arm to shush her, scared as shit.

“No,” she said, shaking me off. “Fuck him.”

This newfound knowledge – understanding that I could toss a “fuck you” over my shoulder if I wanted to – may be how I eventually developed a strong cursing habit.

One day, in eighth grade, we were walking home with what could have been our posse, but wasn’t. Claire and I were the kind of best friends that mostly held onto each other, shrugging others off as mere acquaintances. You know, as middle schoolers do.

But every day when we got off the bus, we walked home with two other young girls, in a pack moving down the sidewalk.

That day, we walked by a group of contractors sitting on a stoop, eating their afternoon meals from paper bags with dirty hands. I’m old enough now, and have acquired enough lived experience, to know that this is a scene where I grit my teeth, repeating “Don’t talk to me, don’t talk to me” inside my skull. But this was my first time, and I didn’t know what to expect.

To be honest, I don’t remember what they said to us. It was one guy in particular who sexualized us with his words, the rest of them hooting and hollering behind them, affirming his masculinity.

What I remember most is what happened next: Claire shooting two middle fingers high into the air as we walked away, the guy shouting back “Stick ‘em up your ass,” and Claire swiveling around to retort, “Better than having your dick up there!” And then we ran home.

It was the first time I’d hurried away from a strange man with the fear of being raped beating wildly in my heart – although it wasn’t the last.

And when I got home, I was so shaken that all I wanted was my mother. So I picked the phone up off the wall, dialed her work number frantically, and waited for her to answer.

After I explained what had happened – leaving out a few of Claire’s choice phrases – my mother was sympathetic for a moment, mostly to my immediate need to be reassured that I was safe now. But then she told me something that has stuck with me ever since, that may have been a major turning point in my life.

She said, “I had to deal with that when I was younger. And so did your grandmother. And so did all of us, back and back and back. It’s the price you pay for being a woman in this world.”

And I had never felt so defeated.

I get it: My mother was trying, in her own way, to let me know that this wasn’t my fault – that this was something that men do to women, that this was an issue much bigger than myself.

But the message that I heard was: “This is just part of life to get used to.”

What I heard was: “There’s no point trying to stop it.”

What I heard was: “You will be violated, repeatedly, for the rest of your time on this earth. So will your daughters, and so will theirs. And we’re powerless to change it because our bodies never belonged to us in the first place.”

And what a shitty thing that is for a mother to impart on a daughter.

All of this is a shitty thing to impart on your daughter.

And yet all of us have a story – or two, or three, or the dozens of others that I couldn’t fit into this space – of being taught how to live quietly in rape culture.

All of us are taught how to live in rape culture – how to think and behave and react in rape culture. But not how to resist, how to heal, how to revolt.

Feminism taught me that.

Feminism taught me that “no” is enough of a response to be respected – and that even insinuating “no” with my body language should be taken seriously.

Feminism taught me that the only reason why boys continue “to be boys” is because we raise them in a culture that prizes toxic masculinity – and that there are, in fact, other ways to parent.

Feminism taught me that my body moving in public space does not make it public property – and that I have all the right in the world to be angry, whether brooding or shouting, when it is verbally violated.

And I am forever thankful to have stumbled upon this brilliant ideology that names my realities and shows me how the culture is to blame, for giving me a framework to understand why what’s happened to me has happened to me, and why the world is so painful to so many.

But I wish it had been my parents who had taught me that instead.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more