Buddha figurine and candles resting on a ledge.

Imagine this: You’re a practicing Christian. You believe in God and Jesus, and you go to church every Sunday. You pray before bed. You even help at church fundraisers.

As you walk into the entrance of your workplace one day, you see a statue of a decapitated Jesus head sitting on the floor decorating the hallway.

How do you feel?

This is a true story.

Except instead of Jesus on the cross, it was a statue of the Buddha.

Buddhism is a religion practiced by nearly 500 million people. There is worldwide reverence for the tradition and its beliefs, which include at the very most basic level: the truth of suffering, the truth of the cause of suffering, the truth of the end of suffering, and the truth of the path that leads to the end of suffering.

You can think of it very simply this way: “Suffering exists; it has a cause; it has an end; and it has a cause to bring about its end.”

Buddhism is complex, comprised of countless teachings and challenging practices.

However, it’s also been taken up as something that’s “cool,” marketable, and consumable. Just walking around my city, I see frequent examples of not only the cultural appropriation of Buddhism, but also uses of it that explicitly counter Buddhist beliefs.

The headless statue is but one of many instances that depict how Buddhism has become decorative and largely meaningless for many.

I can only imagine that the people who displayed it decided to adorn a place of work with a defiled spiritual symbol because it doesn’t indicate a relationship to suffering for them. There was no awareness, no connection, no depth.

After all, if they knew more about Buddhism, they might be aware of the disturbing history of decapitated Buddha statues – which includes invaders and colonizers trying to destroy people’s connection to their faith. Not exactly the most peaceful symbol to choose when you’re trying to create a tranquil atmosphere..

Using Buddhism this way is common within New Age spirituality.

New Age spirituality is often a potpourri of different belief systems sapped of historical and cultural significance with widespread beliefs ranging from occult teachings to UFO enthusiasts.

But resistance to uprooting of spiritual work has been particularly acute and strong in Native communities. In 1993, the international Lakota community declared war against “shamans and plastics” or “Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality.”

They proclaimed, “For too long, we have suffered the unspeakable indignity of having our most precious Lakota ceremonies and spiritual practices desecrated, mocked, and abused by non-Indian ‘wannabes,’ hucksters, cultists, commercial profiteers, and self-styled ‘New Age shamans.’”

For many communities of color, the cultural appropriation of our spirituality means watching our long-held and sacred traditions be disrespected, corrupted and sold at chain stores.

I’m certain folks who are avowed Buddhists or believe in Buddhist tenets have good intentions or are entirely unaware of the implications of their actions. In either case, the next few steps are ways to shift your practice away from causing harm through cultural appropriation.

1. Your Consumption of Buddhism Is Self-Serving

I’m not going to knock mindfulness. It’s an incredibly important part of Buddhism to be present and intentional with your thoughts and actions. Really, mindfulness is a crucial part of living an ethical and good life.

However, when mindfulness and presence are used exclusively as ways to physically improve an individual person’s life, we’re missing the point of Buddhism.

For instance, Whole Foods used to sell these Lesser Evil chips. They were marketed as a way to be “mindful of what you put in your body.” And while yes, it’s great to prioritize eating real food with recognizable ingredients, there’s more to Buddhism than that.

Buddhism seeks to address systems of oppression because they cause human suffering.

But the chips – which tout mindfulness and good choices – were sold at the same store that’s been criticized in the last year for selling artisanal cheese made by prisoners.

Whole Foods has been slammed hard by anti-incarceration activists for selling Haystack Mountain Goat Dairy products – a company partnered with Colorado Correctional Industries (CCI).

And before you think incarcerated men are being given a shot at rehabilitation through this cheese making program, ThinkProgress and Vice report, “[M]any of the inmates participating in CCI’s prison labor programs earn 74 cents a day for hours of labor. Others put the number at 60 cents. The CCI website notes that the labor program is designed to equip inmates with on the job training, skills development, and a sound work ethic. But the extremely low wages make it nearly impossible to afford prison services and basic necessities.”

What makes it possible for things like Lesser Evil chips to exist is an understanding of Buddhism that’s limited to physical goals like eliminating stress in your workday or pesticides in the food you eat. But Buddhism is more about addressing the suffering of the incarcerated men that makes it possible for the place where they sell these chips to turn a profit.

Countless socially engaged Buddhist teachers believe “Buddhist teachings are grounded in a clear recognition of suffering, an ethical commitment to non-harming and an understanding of interdependence: We can’t separate our personal healing and transformation from that of our larger society.”

Which means that while eating better and being more physically healthy are admirable aims for the general wellness of people everywhere, they’re not necessarily Buddhist – because they emphasize you above all else.

And well, that isn’t really Buddhist at all.

2. You’re Using Buddhist Principles as Catchphrases

Do you remember when “zen gardens” were cool? You could buy them everywhere.

They came with tiny little rakes and a little box of sand. There was a moment in the ‘90s when they were all over the movies and big wigs used them as jokes to establish a sense of calm.

Even more recently, one of my favorite movies, Thank You for Smoking, portrayed a Japanese man raking a presumable zen garden in the lobby of a giant Hollywood film agency where big tobacco executives are colluding to sell cigarettes to the masses.

Zen has become a codeword for “unwind,” for “chill.” And that hasn’t gone away. The word “zen” is plastered on candles, incense, and even lotion to that same effect.

Just walking around a health foods store, I can find tons of things that will supposedly bring me “zen.”

Using words like zen to entice consumers with a sense of calm and happiness has become woefully commonplace. But few of these things are actually touching upon zen Buddhist teachings.

Zen Buddhism is a sect of Mahayana Buddhism that emphasizes meditation and personal insight with a focus on benefitting others, impermanence, not-self, dis-ease. Zen Buddhism advocates for a level of spirituality that can’t be accessed through material items or simple words.

Most of the time, products like these are simply banking on Buddhism to make some cash.

Lucky Buddha Enlightened Beer is another example of employing Buddhism to create catchphrases. In this case, instead of zen, it’s enlightenment.

The beer bills itself as “something consistently good natured,” complete with a laughing Buddha on the bottle itself. The website warps Taoist teachings to sell its product by using faux quotes like “If you think that enlightenment is separate from the drinking of beer, you have not yet understood”.

Buddhism is often used in this way to connote harmless – and indeed, ethical – fun. And joy is, of course, a Buddhist tenet. If you’ve ever met a monastic, then you know they’re some of the most lighthearted and cheerful people around. They’re downright a good time.

But this beer and the lotion before it are prime examples of redefining Buddhism to erase its commitment to a greater social good and replace that aim with capitalist profit.

3. Your Sacred Objects Are Purely Decorative

I see prayer flags all the time. And sometimes I wonder, Why not? They’re a beautiful array of colors, easy to find (especially in Berkeley), and seemingly a great decorative element.

A short Pinterest search yielded Tibetan prayer flags used for a “Nepal themed” room, a professional photo shoot, and – my favorite – a “boho offbeat wedding.”

Especially in Berkeley, prayer flags are used like confetti, lanterns, or twinkle lights to decorate barbecues and dinner parties. However, beyond their aesthetic appeal, Tibetan prayer flags are actually sacrosanct objects whose purpose isn’t necessarily to liven up a space.

Tibetan prayer flags are religious.

Sutras – or mantras from three pillars of the great Buddhist Bodhisattvas, conveying things like peace, wisdom, and strength – are written on them. As they blow in the wind, they confer blessings and peace.

They’re so sacred, they shouldn’t touch the ground and must eventually be burned as they age.

And that means it’s rather jarring to see posts like the one below, which clearly indicate the popular use of prayer flags. The author writes that she owns and loves her prayer flags and knows what they stand for:

“However, I’m also not a Buddhist and I do not practice meditation or other Buddhist practices; I have only a cursory understanding of Buddhism. And while the meaning behind the flags may be somewhat simple, their history is not necessarily simple.

I suppose my point is that I don’t want to be an asshole, and I feel like it may be problematic for me to have these displayed, but I also appreciate the symbolism behind them. Any thoughts?”

I love the sentiment behind this blog post because it shows us the bewilderment behind the use of prayer flags: The writer clearly “gets it,” but is reluctant to stop displaying them because—well—racist entitlement.

She feels like she understands cultural appropriation – hell, she even uses that exact phrase to describe what she’s doing – yet she remains hesitant to take them down because she likes them. This is perhaps the very meaning of racial entitlement.

And it doesn’t stop there.

Confusion around things like prayer flags stems from the rampant appropriation of Asian cultural practices (especially religious ones) that has become so commonplace, it’s unacknowledged as racism.

There seems to be an increasing understanding that white people wearing headdresses at Coachella is clearly cultural appropriation, but when it comes to folks putting on bindis, kimonos, or a hijab, we  remain oblivious.

remain oblivious.

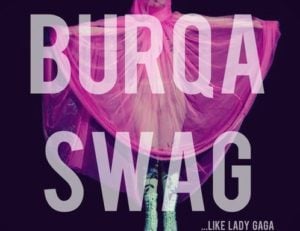

I know this because the perpetrators in this case are Beyoncé, Katy Perry, and Lady Gaga.

And while I love these folks (I’m still listening to Lemonade on repeat), the fact that it’s so widely accepted for mainstream artists to don religious objects as costumes for music videos or performances illustrates that Asian spirituality isn’t treated with the same respect given to objects from Western religions.

4. You’re Not Connecting with Cultural Appropriation as a Form of Suffering

I know a lot of you might still be hesitant to let go of your Tibetan singing bowls, zen body oils, and laughing Buddha statues. Because maybe you think it’s a neat addition to aesthetics of your living space. Or perhaps you’ve even got a cursory connection to Buddhism.

A lot of the cultural appropriation I’m referring to is inadvertent because few people can see the extent to which hollow Buddhist artifacts saturate our daily lives – making it seem okay.

But I encourage all of us to – yes – be more mindful of how we can honor and respect Buddhism as a spiritual practice with meaning and value.

Because cultural appropriation of Buddhism creates suffering for marginalized communities. It tells us that the items and beliefs we hold dear and sacred are meaningless nick knacks or empty sayings you can make into cat memes.

But this is the exact kind of suffering Buddhism seeks to stop.

Because racial justice is an integral part of a Buddhism. Folks like the Buddhist Peace Fellowship see it as a foundational “cultivate the conditions for peace, social justice, and environmental sustainability within our selves, our communities, and the world.”

So if you have Buddhist trinkets that hold little to no value for you? Ditch ’em. At least until you can fully appreciate their significance and/or have a Buddhist practice.

***

My family and I are from a place where Buddhist monks self-immolated in political protest of war. Our country was devastated at unprecedented levels by chemical and physical warfare. Monastics were so connected to the human suffering of that pain that they set their bodies on fire.

For me, and many other Asian Americans, this is Buddhism.

Asian cultural practices are – with painful frequency – stripped of their context and meaning.

But they don’t need to be.

Regardless of your beliefs, I think we can all agree this implicitly Christian country wouldn’t tolerate any of the examples I listed in this article. I mean, who would buy “Our Lord and Savior Popcorn” at Trader Joe’s? Would we ever see “Holy Trinity Relaxation Candles?” Probably not – because we respect white American religious traditions more than Asian ones.

We must engage with Buddhism the same way we would a Judeo Christian religion like Catholicism or Christianity. Failing to provide either with a basic level of reverence is deeply disrespectful and honestly, downright racist.

Just because you’re less familiar a certain spiritual practice, that doesn’t mean it’s okay to disregard its significance to other communities – especially when those communities are marginalized people of color.

Even if you’re less familiar with the history and significance of Buddhist practices, you still have the capacity to tune into empathy and be thoughtful about how your misuse of them can contribute to harm.

And you’re already on your way to understanding more – after reading this, you’ve got the most basic takeaway down.

At its most basic, Buddhism asks you to simply connect to human suffering and bring about its end. Recognizing cultural appropriation is just the beginning of that process.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kim Tran is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s also a collective member of Third Woman Press: Queer and Feminist of Color publishing. Her academic and activist commitments are to laborers, refugee and queer communities. She facilitates workshops on uprooting anti-black racism in Asian American communities. She is finishing her Ph.D in Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley where writes on race, gender and economics. Her work has been featured on Black Girl Dangerous, Nation of Change and the Feminist Wire. She can be found in any of these capacities at www.kimthientran.com.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32