A young person stares very intently into the camera. Blurred in the background are two older people watching over them.

In the short span of two days, two Black men were killed by police.

The first was 37 year old Alton Sterling, who was selling CDs in a Baton Rouge parking lot – something he had been doing for years. His friend and owner of Triple S Food Mart, Abdullah Muflahi, recorded and watched as the police pinned him down, shot him twice in the chest, and then four more times until he died.

The police claim Sterling was a threat, had his gun in his hand. But as my 13 year old nephew said with despair after having watched the footage of his death, Sterling “never reached for that gun.”

One short day later, 32 year old Philando Castile was shot several times during a routine traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota.

Millions witnessed his fiancée Diamond Reynolds live-stream him bleed out in his car. America listened as she calmly narrated the death of the father of their 4-year-old daughter who was sitting in the back seat. We watched as the officer responsible remained—gun pointed—at the dying Castile.

While others have died since, the deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile remain in the national spotlight.

In the 1970s, it was the television footage of the American War in Vietnam war that caused public outcry loud enough for the United States to pull its troops. Similarly, I suspect the videos of these deaths are what make them stick with and move us to shut down freeways.

Both were documented. Both are so accessible you can stream them at any time on YouTube.

So at this point in July, many of us are watching Sterling and Castile die on our laptops, phones, and tablets. At any point, we can type in a name and see the clarity, the callousness of the police and the unnecessary mourning of Black life.

Yet for Asian Americans, Philando Castile’s death hits close to home in an altogether different way. It’s familiar because Diamond Reynolds described the officer who killed Castile, Jeronimo Yanez, as an “Asian American man.”

In 2014, a bullet from the gun of NYPD rookie police officer Peter Liang ricocheted in a Brooklyn stairwell – killing Akai Gurley, who was walking through with his girlfriend. Liang stood by as Gurly died.

In 2016, Liang’s gross incompetence and recklessness earned him only a slap on the wrist – five years probation and 800 hours of community service.

Liang is Chinese American. Gurly, Black.

Liang’s trial and verdict prompted the largest Asian American protests in recent history. Tens of thousands of Asian Americans charged racism at the prospect of one of our own facing up to 15 years in prison – when so many white police officers walked free for worse.

One of my greatest fears is seeing my community make this argument yet again, finding ourselves on the wrong side of anti-Black racism.

Castile’s murder has the potential to create yet another disconnection of our community from racial justice, so the demands of our solidarity are different.

Our own community members are implicated and the veins of anti-Black racism in Asian America are strong. As the protests in Liang’s favor taught us, we have a lot of work to do to heal anti-Black racism in our communities.

Our proximity to the deaths of Gurley and Castile mean that we as a community must work differently to combat anti-Black racism not only at home, but in public, at school, at work, and on the streets. Here are some ways we can do that.

1. Let Racism Be Different

As a person who is not mixed race Black and Asian, I cannot speak to the experience of living with anti-Black racism.

I am a Vietnamese American woman. And while I have lived through poverty, domestic violence, and daily street harassment, my life and those of Black people are not parallel in distinctive ways.

I’m perceived as Asian. I’m not racially profiled as violent or threatening like stereotypes of Black people. Police don’t slam me against the hood of cars. I’m not afraid that my uncles, brothers, or cousins will be shot while playing in the park with toy guns.

Since January, the Guardian counts 566 people have been killed by police brutality. Of that number, 136 are Black and only 10 are Asian/Pacific Islander.

The 10 lives taken indicate that yes, we can be victims of police brutality and it’s important to fight that. But anti-Black racism plays a particularly harrowing role in white supremacy that non-Black Asian Americans can’t relate to.

The experience of being a Black person in this country is distinct from any other kind of racism. African American Studies scholar Jared Sexton calls it different in kind, not degree.

The long list of Black names killed by police which includes unarmed children illustrates this fact.

I am in alignment with the folks who have said we non-Black people of color must listen and bear witness to the violence of this moment.

I watched Diamond Reynold’s video numerous times. I let her pain ring and reverberate around me. I let it be the only thing I heard. I listened as she narrated the death of the father of her child.

More than anything, I allowed it to be different from the racism with which I’m familiar. For me, this is the most important part.

Asian Americans need to let go of the impulse to build bridges across our experiences of racism. There’s no denying that anti-immigrant sentiment is painful and systemically disadvantages Asian Americans in education, the workplace and housing, but it’s markedly different from anti-Black racism.

We need to acknowledge that. We need to sit with it. We need to let it be true.

2. Talk About The Connections Between Our Communities

Because many of us do not experience anti-Black racism, there is an implicit invitation for us to be silent about its causes, effects, and roots.

We need to resist that impulse. We must simultaneously acknowledge that while we don’t experience anti-Black racism, our history with white supremacy provides a connection between our communities.

The model minority myth divides our community from others by teaching us that we’re better than Black and brown people. But now is the time to discuss with anyone who will listen the linkages between the oppression of our communities.

So how do you discuss these connections without erasing anti-Black racism by ignoring the differences between our experiences? Try talking about how our paths have intersected.

Asian Americans were brought into this country as transition labor after the end of formal slavery. For example, South Asians and Chinese folks were the indentured interim laborers brought in to fill the gap left behind by freed slaves.

The Black Civil Rights movement gave our communities the ability to vote. And the model minority myth we deal with and the school to prison pipeline Black communities struggle with are two sides of the same racist educational coin.

So while we live with very different forms of racism, they are connected as obstacles to racial justice. We need to share this information as a part of our community history in order to shift the narrative that we are isolated in our experiences and existence.

3. Take Direction. Do Something.

The Black Lives Matter movement often garners national attention for direct actions. Recently, Black Lives Matter in Toronto stopped the Pride parade for half an hour and demanded police floats be banned from the progression.

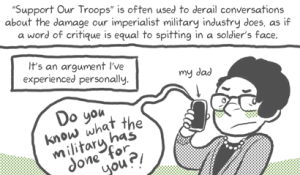

But if you’re like me, maybe you avoid protests and rallies and marches because of mactivism, social anxiety and intergenerational war trauma. (My mom barely survived a revolution and I refuse to trigger her by going to anti-police rallies.)

And that’s okay, because not all resistance looks the same. Moreover, advocating for marches and protests as the only valid form of activism can be ableist.

As Asian Americans, we can use this moment to take part in what Anthony James Williams describes as the “mass redistribution of resources” to build Black futures.

For instance, Issa Rae raised nearly $400,000 for the Alton Sterling’s family by creating a GoFundMe campaign. And this list by Avital Norman Nathman has some great suggestions.

Call your police department. Find out who your local city officials are, call them too.

But bringing this to a new level requires playing the race card. Find out who your Asian American representatives are in City Hall, or the House of Representatives.

There are 11 Asian Americans in Congress and one in the Senate. I don’t know about you, but I can certainly make 11 phone calls in one day.

You could even write out a short script that might read:

“Hi Congressperson ______. My name is a ____ and I’m a voter in your district. I want an end to police brutality against the Black community. This is an important issue to me as an Asian American voter because it stands in the way of social justice for all communities of color.”

Make it explicit that this needs to change, that it’s an issue that relates to our community.

4. Create Culturally Relevant Material

There’s a Google docletter going around Asian American community.

It relays the importance of Black Lives Matter to us as the children and family of Asian Americans. The letter itself is translated into numerous Asian languages and respectful of cultural norms.

Projects like these are vital if we’re going to bring our elders and monolingual Asian folks into our struggle for racial justice. We have to use their language and speak in ways that appeal to them as our caregivers, guardians, loved ones.

But we could push even harder.

When my uncle was alive, he would listen to Vietnamese radio. All day. Everyday. For hours. We’d get annoyed, but it was his way of connecting with Vietnam and the issues that were important both to Vietnam and the diaspora.

I wonder what he would think if that radio station covered Black Lives Matter.

We could check in with our ethnic media – the radio stations, the newspapers, the TV stations – and make sure they’re covering these deaths. We could ask them to be on the side of racial justice with us.

5. Utilize Your Cultural Space

We could publicly mourn the loss of Black life in Asian spaces.

There are a lot of vigils right now, but we could also organize them in our ethnic enclaves – because creating space for cross racial solidarity is important. If vigils are already happening and we’re physically able, we could just go.

Light a candle. Stand in solidarity. Our cultural spaces need to value Black people by bringing those events.

One Buddhist altar is a small step toward a greater systemic solidarity.

Toward that end, buy #BlackLivesMatter signs (proceeds go to the movement) and post them in your car, in your windows, at your school, at your work and religious space. Ask Asian American store owners if they would be open to doing the same.

Numerous studies show the positive effect of visible welcoming signs for LGBTQIA+ communities, but we need to do the same for Black folks.

We need to say that – despite membership of these police in our communities – we believe in Black futures.

***

Nothing I’ve suggested is groundbreaking or even particularly inventive, but it comes from a place of hearing the pain of a community and seeing the narrative of division between us.

Now is the time for us to act with informed intention and to be in solidarity by not making false equivalencies of our experiences of racism.

Maybe more than anything, now is the time to make sure our elders, our religious leaders, our Little Saigons, Chinatowns and Japantowns reflect #BlackLivesMatter.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kim Tran is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s also a collective member of Third Woman Press: Queer and Feminist of Color publishing. Her academic and activist commitments are to laborers, refugee and queer communities. She facilitates workshops on uprooting anti-black racism in Asian American communities. She is finishing her Ph.D in Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley where writes on race, gender and economics. Her work has been featured on Black Girl Dangerous, Nation of Change and the Feminist Wire. She can be found in any of these capacities at www.kimthientran.com.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more