A person holding a tray of seedlings in a garden, smiling.

Growing up as a sensitive child in liberal Eugene, Oregon during the 1960s, I remember being quite upset by the growing environmental disasters of that time period, such as the Cuyahoya River in Ohio catching on fire, and the Hudson River registering bacteria 170 times the limit considered safe.

Although young, I watched the news and learned about these problems in school and participated in the first Earth Day, on April 22, 1970, which happened right before I turned thirteen. I went home from junior high that day, recognized myself as an environmentalist, and immediately announced to my mother that our household must start recycling or “the planet was going to die.”

Even upon entering college at the University of Oregon, I stayed informed and began doing activism, mostly against herbicide/pesticide use and nuclear power. Ironically, I was accidentally sprayed by a tree spray (pesticide) truck in March 1978, and a few months later was diagnosed with melanoma, in cloudy rainy pre-global-warming Eugene.

Getting cancer after pesticide exposure may have been a coincidence, but considering my lack of a tan, and what information I have about pesticides being sprayed in neighborhoods (which is now banned, thanks to the work of environmentalists), my sense is the cancer was from chemical exposure.

As my knowledge about environmental destruction and corresponding cancer rate increases grew, my passion for “saving the planet” grew.

I viewed the health of the planet’s ecology as directly related to the health of myself and other humans.

Although I value my fiery young years of environmental activism, which continues at a slower pace even today, I also cringe at some of the entitled assumptions I made about everyone else in the world.

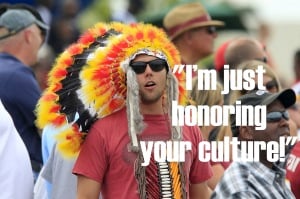

Part of the spirit behind this article is to broaden the discussion of environmentalism, to acknowledge that entitlement within the environmental movement is giving it a bad reputation, and offer solutions to repair that reputation.

Here are 5 tips on how to be an environmentalist without entitlement.

1. Acknowledge Your Privilege

When I was a young environmentalist, I did not understand why more people in my hometown were not joining me in riding my bike everywhere or spending hours gathering signatures on petitions. I did not understand why more people were not fighting pesticide spraying and nuclear power plants.

After all, these things could create cancer and suffering, and destroy the natural beauty I loved so much in the Pacific Northwest as well as all over the world.

What I did not acknowledge is that my privilege enabled me to spend so much time and effort with activism.

I was born into a white, middle-class/upper-middle-class family. My father was a professor at the University of Oregon. My mother was a homemaker who spent significant amounts of time doing volunteer work for local planning commissions, as well as the ACLU. I had my college education paid for, worked part-time and mostly went to school and studied.

I had the time in-between classes and tests to work on saving the planet. Yes, I acknowledge that I spent my vacations reading for my rigorous classes and researching how dangerous nuclear power was – not partying it up like many other college students. I truly did work hard to try and do something for this blue spinning ball called Earth.

However, I was never in danger of homelessness or poverty; I had little clue how very privileged I was. I had the economic luxury of the time to do environmental activism.

Although my parents instilled in me the sense that I was fortunate and should give back, there was no discussion of our white privilege. My parents taught me to respect Dr. Martin Luther King, and to not be overtly racist, sure. But they had no concept of their own white privilege, and did not know how to relate to the people speaking of white supremacy at the time.

They also had no knowledge of generational trauma, PTSD, addiction, depression, and anxiety, and what any and all of those issues can do to a family’s economic health.

They were ignorant about how existing systems in America favored their development over the development of other families of less privilege — that or they just didn’t want to think about it.

Over the years, as I moved away to different parts of the country, and stayed open-minded to new information, I recognized my privilege. And I adjusted my outlook.

Nowadays I see people who are privileged with a whole new set of environmentalist principles that are very difficult to follow.

For instance, the hybrid car. Buying a hybrid car costs more, although in about 8 years the cheaper gas does indeed pay for itself. And, they are great cars as far as having a lower carbon footprint.

However, many Americans can’t pay the 5-8000 dollars more to get a hybrid. To suggest they must, is to show your entitlement.

Similarly, a significant amount of people who have low incomes and/or live in “food deserts” do not have a car, and end up buying their food at whatever store is closest to where they live. Often, it is the corner store or liquor store, with limited options on what to buy. To act shocked that someone is “still buying food made by corrupt giant food companies who exploit their workers,” is, again, entitled.

Having a privileged outlook alienates you from others and does not help the planet, the farmworkers, or anyone else. Instead, acknowledge that you have privilege, and you use it for good. Which brings me to my second tip.

2. Start Where You Are

Shrinking down in guilt over having privilege serves nobody, so how about put it to good use. Look at where you are, right now, and what you can do.

Part of that process is building community and inserting care for the planet, in a natural way, into your community. Are you in a neighborhood where not everyone has a car? Or, for instance, do you have neighbors with age-related eye issues, or other disabilities, who can no longer drive?

Do you say “Hi!” to your neighbors when you leave your apartment or house? Do you ever chat with them? Well, if not, perhaps it is time to do so.

Perhaps start with a simple, “Hey, I am driving to the Co-op to get my 50-lb bag of organic brown rice. Do you need anything at the Co-op?” You would be amazed at what could unfold by that opening line.

For all you know, your neighbor will gladly hop in the car with you, if given the chance.

Is there a community garden in your neighborhood? Is there a neighborhood association you can join? Can you introduce a motion to start a community garden?

Even if you don’t garden, you can help by sending out emails, talking to neighbors about the garden project, and so on. The dialogue about organic versus non-organic can begin there.

Don’t push your agenda.

Take the organic issue, for instance. You may be passionate about how organic produce is better for the farmworkers as well as the planet. I get it; I am in agreement. But, don’t be fanatical.

Your neighbor may have a pear tree that they did not spray this year, but maybe they used spray on it last year. So what! Trade the organic carrots from your garden for the pears! When you do, perhaps share a tip about tending the soil near the tree in a more natural way.

Most likely your neighbor will end up teaching you more than you teach your neighbor.

Don’t assume you know more, because most likely, you don’t – especially if you recently moved into the area. There are a thousand other examples of the principle of starting with where you are, and growing from there.

3. Spend Less

I wanted to hear from a variety of people about this topic, and one of the things I heard from several people was that spending less money often leads to people making more ecological choices in life.

Simon, a book store owner in Oregon in his early 60’s, summed it up by saying “Nobody is entitled to do everything.” One of his complaints about environmental hypocrisy is that environmentalists can often engage in a sort of conspicuous consumption culture.

He gave me the example of this, by pointing out that the mayor of his small city was flying to Beijing for a climate conference; flying in jets is a huge source of carbon footprint, so the irony of the mayor’s trip did not escape me. Simon’s suggestion of a statewide conference, with a possible video link-up with Beijing, certainly made more sense than the mayor of his city flying across the world.

We also discussed the growing popularity of “Eco-Tourism;” supposedly “green” tours to the Amazon or the Artic, where once again massive amounts of jet travel are involved, thereby negating much of the “ecological value” of the trip itself.

While there is nothing horrible about visiting a country far away, the point I am making is that it is insincere to refer to the trip as ecological. Putting in two hours working at a community garden every week is doing something ecological; how about we focus on things like that!

Isabel, a 21-year-old urban farmer and activist from California, points out, “The US economy is inherently environmentally destructive.”

While this statement may be controversial, she then suggests that simple steps such as wearing used clothes, recycling and re-using materials as much as possible, and growing as much food as you can, is more gentle on the planet. Isabel believes what many others believe, that cycling instead of driving is a great choice. However, she acknowledges that not everyone is physically able to cycle, and believes mass transit can and should be made available to more people.

4. Being Intentional in Everyday Ways

Both Simon, Isabel, and several other people agreed that “green” marketing campaigns are usually just a gimmick to sell more product. Being intentional and watching how much of everything you use can go a long way to helping the environment.

One example of that can be found by watching Judy, an automotive repair shop owner in California. Judy, who currently has her adult son staying with her in her small house, as well as frequent guests, uses one-quarter of the average amount of water for a home in her area. That is obviously no small task, as everyone in her town is trying hard to conserve water.

Judy skips showers on days where she does not get too dirty, she keeps the same pair of coveralls at work to slip into all week long, she has developed an extremely low-water-use method of dish washing, and has drought-resistant-foliage in her yard.

As far as water use goes, Judy is a model citizen — sadly, she receives no tax incentive for this while water bills continue to go up in her area, even as consumption goes down, because of the drastic increase in per-gallon-rate.

But, the oppressive politics of water can be discussed in another article!

While working, Judy keeps an old bike at a nearby tire and alignment shop she partners with. She drives the customer’s car from her shop to the tire shop, then hops on her bike and pedals back to her shop. When the customer’s car is done, she pedals back to the tire shop, parks the bike, and drives the customer’s car back.

Similarly, Judy has another small folding bike in her shop, for the occasional customer’s car that needs to go to the smog shop or muffler shop. She drives the customer’s car to those places, uses the folding bike to go back to her shop, and then the folding bike to go back and pick up the customer’s car.

Over the years, the amount of carbon Judy does not produce in these small trips adds up, and helps. She saves money, saves time by avoiding cross-town traffic, and she spares the air a bit, as well.

Judy does not view herself as an environmentalist; she identifies as politically conservative, but with a deep respect for the earth. She emphatically declares that as far as taking better care of the earth goes, “Everyone can do it!”

5. Join Forces with Other Groups

Another way environmentalists can avoid entitlement is to work closely with other groups in their local area.

Raven, a retiree and transgender activist in Oregon, believes strongly in “multi-agency involvement in community gardens and other projects.” She points out that gardening projects in a community can be highly educational, and spread information naturally about the importance of drought-resistant, organic, non-gmo crops.

Different growth-staged-crops can keep gardens growing longer, thus producing more food. She cites an example of gardening done collectively by local schools, the local HIV Alliance, Centro Latino Americano, and other groups. Raven points out that gardening is a very basic way to see the value of the environment, and the only way the planet will survive is if everyone works together.

Raven’s point is completely sound for every other environmental issue. Clean air and water, or the lack of, affects everyone. Adequate amounts of natural open space, or the lack thereof, affects everyone. Working locally is the best way to get things done.

Peter, an attorney in California, suggests community groups can begin proactively stopping future environmental disasters by working together locally and passing local ordinances. For instance, passing a county-wide anti-fracking ballot measure before the large corporation comes in and fracks is easier to do that fight the fracking giant afterwards.

***

In conclusion, perhaps the environmental movement needs to stop separating itself as a movement, and just naturally integrate into local communities, doing what they can, when they can, in a natural way.

Our environment is just that: our environment.

Over the years I have met thousands of people who, although they may not view themselves as “an environmentalist,” care deeply about the planet.

When given natural, local, and sensible ways to care for the earth, 99% of the people I have met will take those earth-friendly choices. Working locally, in conjunction with existing community groups, will hopefully keep our planet, and its inhabitants, alive and healthy forever.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Amy Ballard Rich is a retired preschool teacher, and published poet, living in Eugene, Oregon. She has a long activist history, and tries to still show up to lend her voice as an ally to stop environmental racism in its many forms, such as stopping oil pipelines on Native reservations. When not writing or protesting, Amy can be found jogging through forests, occasionally stopping to hug a tree.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32