A person standing in a street, smiling and holding a white placard with the word “Racism” in a cross-out circle.

Nothing upsets White Americans like calling them a “racist.” It can spark outright indignation, extreme defensiveness, a faucet of tears, and a host of emotions that dwell in our primal selves.

Why do White Americans fear the word so much?

Over the past 15 years of teaching about race and racism at the high school level, I have polled my students on their associations with word “racist.” The list is relatively consistent from year to year: the Confederate flag, the Ku Klux Klan, burning crosses, white sheets.

In other words, they consistently associate “racist” with the symbols of the most egregious and deadly forms of White Supremacy.

No wonder so many White Americans flee from racism.

But fleeing racism is the primary way we as White Americans support, protect, and perpetuate racism. Here’s why:

When we bolt, we don’t discuss racism. We don’t analyze it. We don’t even face it. We are too busy creating distance, with our backs turned.

In short, fleeing precludes the necessary process of discovery that transforms an ignorant White American to one we desperately need: an anti-racist White activist.

Consequently, the status quo remains with its nails sunk deep into the future.

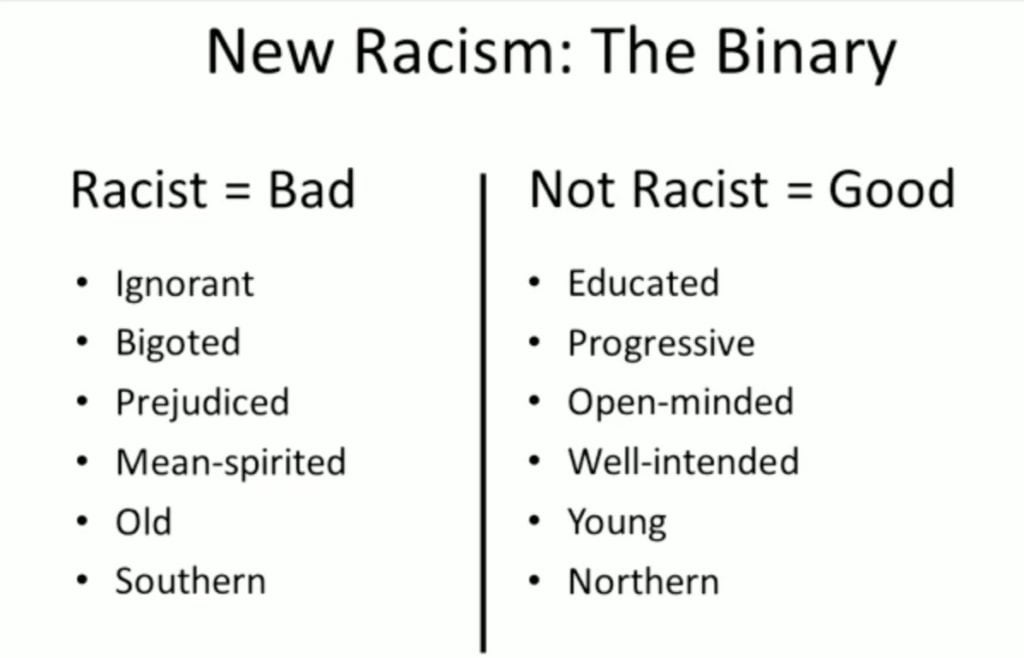

Robin DiAngelo, a scholar who writes extensively on whiteness, explains these responses as an inevitable outcome of what she calls the “good/bad binary.” As White Americans, we think of racism as bad, so if we hold a racist belief, then we too are bad. Conversely, if we hate racism, then we are good.

To many White Americans, even exploring the concept of the White Privilege confines them to the binary, condemning them as evil racists and sending them packing.

My students’ associations with “racist” perfectly exemplify this binary.

But if we White Americans truly hate racism, then we can’t distance ourselves from it.

After all, what threat has ever ended because we turned and fled?

Like espousing colorblindness, distancing yourself from racism is a flawed strategy. Here’s what we need to do instead:

1. Break the Good/Bad Binary

Dissociate the egregious symbols of White Supremacy from the concept of racism. Racist messages are everywhere.

The question isn’t how could you hold racist beliefs, but rather, how could you not hold racist beliefs?

Beverly Daniel Tatum – in her classic text on racism, Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? – compares racism to smog. We are all breathing it in; we are all affected.

So cut yourself some slack if you have internalized racist ideas. It doesn’t mean you are bad; it means you watched Peter Pan as a kid (or the thousands of other biased films and television shows). It means you were likely raised by folks who too fled racism.

Then repeat the following:

“I can internalize racist beliefs and still be a good person.”

“I can internalize racist beliefs and still be a good person.”

“I can internalize racist beliefs and still be a good person.”

And that statement can be true, as long as you complete this next step.

2. Unearth Your Racism and Challenge It

Most of our racial biases go unnoticed. There’s even a name for them: Implicit biases, which can be defined as the “thoughts about people you didn’t know you had.”

Remember that smog? It means our bodies are full of polluted thoughts. Even mine. Even yours.

And arguably, implicit bias – not conscious racism – is what accounts for many of the disparities highlighted in this three-minute video.

But you are never going to unearth these biases until you finally pick up the shovel. In other words, it takes work – deliberate and sustained effort.

You must actively bring your implicit biases to the surface. (There’s even a test for them here!) You must actively challenge the stereotypes you have internalized (which generally don’t hold up). You must actively learn about microaggressions and cultural appropriation so that you aren’t perpetrating them.

Do the work, and you won’t be able to help but repeat the inevitable:

“I am racist.”

“I am racist.”

“I am racist.”

If enough White Americans repeated this statement– and did so loudly – the word “racist” would lose its debilitating power over us.

Instead of signaling us to flee, it would remind us to reach again for that shovel, ready for some strenuous self-examination.

If we practiced repeating these words, perhaps no one would need to declare:

BLACK LIVES > WHITE FEELINGS

3. Understand Systemic Racism – Deeply

Systemic racism, also known as institutional racism, is the “policies, practice, and procedures that work to the benefit of white people and the detriment of people of color.”

Some even make a distinction between institutional racism and structural racism, which is the “interplay of policies, practices, and programs of differing institutions which leads to adverse outcomes and conditions for communities of color compared to white communities.”

The point is: Racism is bigger than one person; it’s not about you.

At the same time – and I don’t think this is stressed enough – individuals make up systems.

White individuals can become cashiers who make the checkout line an unpleasant experience for shoppers of Color. White individuals can become teachers who don’t recognize the brilliance of their students of Color. White individuals will invariably make up many hiring committees, holding the keys that open the doors to upward mobility.

Thus, it’s crucial to analyze how the individual interacts with and connects to the institution.

One of the best primers on institutional racism is Robin DiAngelo’s “Deconstructing White Privilege.”

Note that when exploring racism, DiAngelo argues that we must go deeper than the obvious – the racial slurs and racist jokes. If you’re new to exploring systemic racism and you think you get it, there’s a good chance you have not dug deeply enough.

4. Take Action

Dismantling these systems will require action. Awareness and education are certainly part of the process but, alone, they are not enough.

Recently, students at Seattle University staged a three-week-long sit-in to challenge a whitewashed humanities curriculum, forcing their problematic dean to retire. Students at San Francisco State University led a 10-day hunger strike to win crucial funding for their perpetually underfunded College of Ethnic Studies.

Awareness did not win these victories. And keep in mind that it was the educational systems themselves that opposed the students.

Thus, not only is education not necessarily the solution, but it’s often the problem.

Racial injustice infects pretty much every facet of our world.

This fact can be overwhelming, but it also makes it relatively easy to find a struggle to join. Maybe it’s at your workplace, in your child’s school, in front of your computer, or on the streets during rush hour.

There is no shortage of ways to act. In fact, in a search engine of your choice, type the words “White people fight racism” and you will find endless articles with ideas (many of which are compiled here).

While too many White Americans still get racism wrong, the Black Lives Matter movement has led to the burgeoning of anti-racist organizations, like Showing Up for Racial Justice, made specifically for White Americans who want to, well, show up for racial justice.

***

But don’t wait.

The epitome of White Privilege is this country losing another Alton Sterling and Philando Castile and Deeniquia Dodds and Korryn Gaines and Paul O’Neal while we wait for a critical mass of White Americans to wake the fuck up.

And waking up begins with discussing racism, analyzing racism, and facing racism – especially our own.

Paradoxically, waking up means building a relationship with racism, not fleeing from it.

Once we do, the word “racist” won’t incite debilitating behaviors but instead will foster meaningful change and racial justice.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Jon Greenberg is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. He is an award-winning public high school teacher in Seattle who has gained broader recognition for standing up for racial dialogue in the classroom — with widespread support from community — while a school district attempted to stifle it. To learn more about Jon Greenberg and the Race Curriculum Controversy, visit his website citizenshipandsocialjustice.com. You can also follow him on Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter @citizenshipsj.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more