A person stands with their eyes shut and their hands over their ears.

Here’s a familiar scenario that you might have experienced. I’ll be in a room full of people when a friend tries really hard to point someone out.

“Do you see that woman? She’s wearing a blue shirt… she’s taller. Um, she’s the one with dark hair. Hmm, can you see that she’s wearing a gold necklace? Okay, kind of darker skin?”

Lots of intermittent, uncomfortable silences as friend tries to describe this other person to me without saying their race.

Sometimes, you might be the one tiptoeing around race – as if naming the identities associated with race is the singular act that conjures racial injustice.

Claiming not to “see” race, avoiding race, or refusing to acknowledge racism exists – this is called “colorblindness.”

Another very recent example of a colorblind approach to race is when Justin Timberlake responded to Jesse Williams’ speech at the BET Awards by tweeting, “ I really do feel that we are all one… A human race.”

While you may think the idea of getting rid of racism by getting rid of the idea of race seems like a simple enough idea, eradicating a centuries-old global system of oppression by pretending the system no longer exists doesn’t actually make racism disappear. In fact, “colorblindness” contributes to and sustains racism’s ongoing existence.

Colorblindness in the United States is a historically constructed strategy that upholds racism and white supremacy.

So, where did this particular ideology of not “seeing” race come from? What are the origins of “colorblindness” and what are their current consequences?

Here’s the disturbing legacy you’re building on if you take a “colorblind” approach to race.

1. Erasing Race Solves International Public Relations Problem Around Racism

For those that live in the US and/or have the privilege of citizenship, think of the reasons you’re glad to live here.

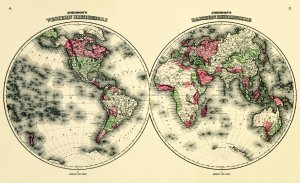

The United States, as well as democracy and capitalism, are kind of like products. They need to branded, marketed, and ultimately, bought into.

On a daily basis, students pledge allegiance to the flag in their classrooms and people sing and stand for our anthem at events. We have journalists and politicians tell us that our military fights for our freedom.

Since it’s election season in the US, candidates and their political supporters keep saying things like: We’re a great nation. A strong, resilient nation. We must stand united. We’re spirited. Innovative. Any of this sound familiar?

A long-standing marketing tactic of the US has been celebrating freedom at home while looking overseas to point fingers at tyranny and oppression.

But can you think of a time, either historical or current, that the US might have a bit of a public relations problem when it comes to oppression at home, specifically around race?

History shows us plenty of examples.

For instance, after World War II, both the Soviet Union and the United States wanted to establish themselves in the international arena as the supreme economic and political power. As the US sought to promote capitalism and democracy against the enemy of communism, it needed to create and maintain its own vision of freedom.

In order to legitimize its own rhetoric around democracy and freedom, the US needed to overcome its own long history of racism. With World War II often framed as a war to combat racial and religious intolerance, addressing racism in the US was imperative.

At the time, racism at home in the US was international news.

One headline-making case was the sentencing of Jimmy Wilson, a Black farm laborer in Alabama who was sentenced to death by an all-white jury after being convicted of stealing $1.95 from his employer. Around the world, headlines decried this death sentence as evidence of the United States’ failure to bring its own democratic principles home.

How could the US possibly justify itself as a place of freedom if it allowed such racial injustice?

How could the US be a place of democracy if it continued to allow Jim Crow laws enforcing racial segregation to exist? Or redeem itself after the internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans and the establishment of exclusive immigration policies?

These contradictions between the United States’ political ideology and racist practices at home tarnished US national identity. In short, the country had re-branding work to do.

The US needed to re-envision itself as a society without racial hierarchy in both policy-making and ideological, cultural shifts.

The organizing work of activists, leaders, and communities during the Civil Rights era passed significant policies towards racial equity and ended Jim Crow laws.

These were crucial, hard-won victories for people of color that should not be diminished or dismissed.

However, in the midst of the Cold War, the US government leveraged these important Civil Rights moments to stabilize its own global power by re-creating its own identity as a democratic, anti-racist savior.

Although more radical visions of racial justice existed and activist movements strove for a wider breadth and depth social change, broader critiques of racial oppression practices in the US were perceived as “disloyal” and unpatriotic.

How much can you really be proud of your country’s “freedom” when this freedom, and this democracy, continues to be limited and only be available to some?

Don’t fall for the deception – if you buy into the “colorblind” ideology, you’re directly participating in a narrative designed to cover up ongoing oppressive atrocities.

2. ‘Colorblindness’ Allows Government Policy to Appear Non-Racist

Would you be satisfied with reforms that only made the US look good on the surface?

On one hand, policies forbade explicit types of racism, such as the segregation of public spaces and resources. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, religion, sex, and national origin.

For the US government, these reforms were sufficient. With overt practices of racism officially deemed illegal, that seems good enough right?

Wrong. Racial inequities still persist.

However, with explicit forms of racism now forbidden, it becomes more difficult to continue holding institutions and systems accountable.

Social issues like poverty and unemployment that disproportionately impact communities of color became an individual’s responsibility.

With the national narrative that racism was gone, disappeared, and over, individual failure was to blame rather than the government. This is also known as being “post-racial.”

“Colorblindness” maintains systemic racism without appearing racist.

In addition, because overt racial discrimination was illegal, biased practices like government surveillance and housing discrimination find other ways to target people racially without actually naming race.

This kind of discrimination may be against the law – but you can probably still name some examples of racism, so obviously the problem’s not solved.

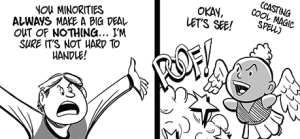

Those who take the “colorblind” approach may avoid naming race, but still participate in racism.

Daily microaggressions, while not against the law, can have deeply negative impacts.

As microaggressions are about the impact and not the intent, then accumulated over time, they can lead to deeply oppressive results that undermine US ideas of “freedom” in a fundamental way.

As a society, we constantly question the right of certain bodies to belong in different spaces.

Black and brown bodies can appear to us as anomalous in academic settings, Asian and Latinx bodies seem questionable in their citizenship. We demand justifications for these presences.

However, snap judgments that assume someone’s potential for criminal activity, that judge someone’s supposed citizenship status and immigration history, and/or presume someone’s right to govern themselves can be devastating.

For example, in 48 states, people who are incarcerated don’t have the right to vote – however, incarceration rates disproportionately affect men of color as they are more likely to be stopped, searched, and also arrested.

Because of this, plus felony disenfranchisement laws, 1 in 13 Black people have lost their voting rights.

Immigrants living in the United States without documentation pay billions in taxes, yet don’t have the privilege to access primary healthcare or even drive without risking detainment. 60,000 immigrants are held in detention centers on a daily basis, where individuals are separated from their families and also receive little to no legal representation.

While continuing to strip land away from Native people, the US government also continues to deny the sovereignty and tribal authority of Native Nations in ways that are violent for communities. Federal law prohibits Tribal courts from prosecuting non-Natives on trial lands, regardless of the crime (whereas Natives can be punished twice – once in federal court and again in tribal court).

3. ‘Colorblindness’ Is Connected to the Myth of Meritocracy

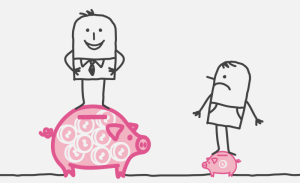

The “American Dream” continues alongside the rise of “colorblind” racial ideologies. Freedom, or perhaps the much proclaimed “pursuit of happiness,” is depicted as upward social mobility and wealth accumulation – two things claimed to be attained through hard work.

The economic successes of some people of color served as a way to enforce conformity with the “American Dream” and also help make racism seem as if it were disappearing.

In this way, the US could be the global model for racial integration and, as success was defined solely in terms of economics, the US could also promote capitalism as a benefit of anti-racism.

In 1966, publications like the New York Times and US News and World Report reported articles proclaiming the “success stories” of Japanese Americans and Chinese Americans.

One story included the line: “At a time when it is being proposed that hundreds of billions be spent on uplifting . . . minorities, the nation’s 300,000 Chinese Americans are moving ahead on their own with no help from anyone else”

These narratives promoted both the model minority myth and the myth of meritocracy, and they were specifically directed towards Black Americans demanding racial justice.

The lesson was that hard work alone could supposedly erase struggles caused by racial injustice. If Chinese and Japanese Americans could achieve success against all odds, racial inequity no longer truly existed.

“Failures” of economic success by other communities of color, particularly Black, Latinx, and Native American communities, became their fault. Rather than addressing past and present structural barriers, these communities were depicted by the government and mainstream media as simply not working hard enough.

The myth of meritocracy tells us to believe that our success is due solely to our own talent and hard work, but we end up ignoring other factors and outside help that contributes to our achievements.

This myth is linked to the ideology of colorblindness, as people think that colorblindness operates as a way to treat everyone fairly.

We tell ourselves that because we worked hard, we deserve our successes.

Because of “colorblind” ideology, we might dismiss and invalidate people who point towards occurrences of racism as obstacles by saying things like “Stop playing the race card” or “Not everything’s about race!”

We are unable to see the ways institutions and systems are set up to be barriers to some but not all.

Yet, different social conditions impact someone’s various identities, such as race, positively and negatively. The idea that we can’t “see” race and thus are all the same, treated the same, and have the same opportunities, is false.

***

Several years ago, Barack Obama’s election to presidency signaled to some that the “racial wounds” of the United States had finally healed – that we, as a nation, were completely post-racial and post-racist because we had a Black president.

You might believe that if one Black man could be president, that truly, race could no longer be a barrier.

“Colorblind” approaches to race create the illusion of equity while simultaneously maintaining inequity. We can’t afford to live in this dangerous fantasy, as racism continues to urgently necessary for us to face and address.

We must remember that in this moment, where some continue to refuse to “see” race or acknowledge the existence of racism, that Black people are dying because police “see” their bodies as inherently dangerous. That our society is not safe for queer people of color. That Muslims or those who “look” Muslim are blamed and criminalized for all attacks of terrorism.

That we live in a nation where people of color are killed, deported, and violated under the law.

At this moment, how could we possibly pretend racism is over?

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Rachel Kuo is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a scholar and educator based in New York City. Her professional background is in designing curriculum and also communications strategy for social justice education initiatives. You can follow her on Twitter @rachelkuo.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more