A group of three people having a discussion while seated outdoors.

Y’all, we need to change the way we talk about power, privilege, and oppression.

When I am in spaces dedicated to addressing institutional racism and other forms of injustice, I too often encounter folks who, in an attempt to be conscientious and empathetic, make comments that are actually very violent. Only it’s a violence so subtle and implicit it can be difficult to name, and as a result, almost never addressed or discussed.

I’m sure you’ve heard them too – maybe even made a few of these comments yourself: “We all deserve equal rights!” “Minorities should have the same opportunities as me!”

In these moments, I die on the inside – it’s so uncomfortable to hear attempts at empathy and divestment from white privilege when they are all unintentionally wrapped up in commentary that reinforces my oppression.

I also find that “woke” white folks who want to demonstrate their social justice credentials spend a good amount of time reiterating the term “white privilege” or referencing their “being white” – without saying what that even means for people, like me, who are not white. As if naming their whiteness means something so significant to shifting power or cultivating change.

In reality, it just shows me that they feel safe enough to name their power without naming the brutality that maintains it, as if stating the identity of those in dominant groups (note: dominance in terms of access to power and acceptability) becomes a wild card in social justice uno.

Simply put, it seems that many of these codified, justice-centered terms actually work to normalize oppressive culture far more than they fight against it.

Empty words that dance around the violence we are subjected to as people of color do not help to dismantle white supremacy, nor do they shift power away from whiteness and white supremacy.

For example, after Mike Brown, Aiyanna Stanley-Jones, Mya Hall, Sandra Bland, the countless other black folks who have been murdered by the police, and society’s resulting outcry over the heightened visibility of police brutality and explicit forms of racism, police departments around the country began to focus on increasing inclusivity trainings and tolerance programs. But increasing trainings around “inclusivity” doesn’t address the source of and pervasiveness of white supremacist violence.

This is a great example of how strategic, justice-themed words are used as harm-reductive tools to maintain power while uplifting our cultural and political practice of silencing, gaslighting, and keeping secret the named violence around racism.

Empty terms such as “racial profiling” and “ignorance” speak to shallow versions of addressing deep-rooted issues of anti-Blackness, misogynoir, plantation politics, and xenophobia.

This strategic and specific language white people have systematically appropriated to create a false sense of change and inclusivity actually just maintains white supremacist capitalism within our interpersonal and institutional navigation.

In order to cultivate effective spaces and environments around anti-racism and anti-oppression, we need to begin talking about how language shapes, perpetuates, and maintains violence in our everyday lives. We need to decolonize that language if we truly want to shift power, create change, and implement learning and growth around structural racism and anti-Blackness.

The following are six common terms that are seen as anti-oppressive, but are actually just progressive rubbish that deceptively protects the status quo.

1. Diversity

During the Mizzou student protests in November of last year, we saw a rise in conversations of diversity within academic and higher learning institutions. The term and concept of “diversity” was used to “further” the conversation about campus culture, yet no institutions or institution officials actually named the violence within their environments that make it necessary to diversify.

If we don’t name the violence, how do we address it? Do black and brown bodies in a room signify diversity if everything else stays the same?

Using the term diversity does not guarantee action, change, or even shallow attempts at addressing violence and erasure within institutions.

Instead it speaks to the reality that normal means white, and maintains that white people can integrate people of color into white spaces on their terms – rather than contextualize the structural and individual violence that exists in creating these conditions that require us to have said “diversity.”

Diversity as a term, word, and concept keeps white people comfortable, while maintaining power and violence through implicit racism in our everyday navigation. Diversity is the wool being pulled over our eyes that forces us to imagine change is happening when we can’t see it or feel it.

Similarly, multiculturalism is another term that groups everyone together without a specific focus on what the state of the status quo culture really is.

If whiteness is deemed as the cookie cutter global standard – which it is – what does multiculturalism represent to those operating under the assumption that white is the everyday, but black and brown cultures are tokenized holidays?

Who are terms like multiculturalism and diversity for if they are defined and determined by white people?

If institutions are unwilling to divest from privatized prisons; unwilling to stop gentrifying poor black and brown areas for their capitalistic expansion; or are unwilling to name that the black, indigenous, and non-black people of color are suffering from system racism from their textbooks to their financial aid, then there is no diversity or multicultural implementation plan.

Diversity and multiculturalism remain a part of the mythologies of whiteness.

To challenge diversity catch-all ideals, it takes naming the structural and interpersonal racist violence behind the concept of diversity is the way to help cultivate anti-racist spaces and anti-racist rhetoric.

2. Equality/Equity

Often, within our conversations about feminism and about justice, the term “equality” is thrown around as the end all, be all solution to oppression. White people champion for equality from the HRC to shallow Affirmative Action conversations, but do not actually realize that equality is not a potential reality.

Equality as a concept does not work under white supremacist capitalism, as our current oppressive power systems are inexplicably linked to oppressing someone. Under capitalism, there is always a winner, meaning there is also always a loser.

So ultimately, if we were able to access equality to our oppressors, someone else would need to be oppressed in our place. Is that really what we want?

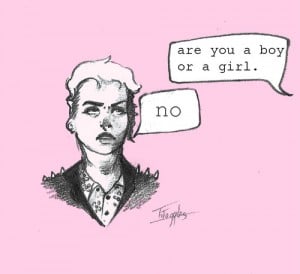

Even if we could access this concept of equality, it would also beg the question of who would receive equality when our oppression and privilege is not made up of even, equal parts. Intersectionality complicates our identities and our navigation, therefore your equality would never equivocate to my equality without dismantling anti-Blackness, white supremacist capitalism, ableism, transphobia, gender violence, the policing/surveillance of bodies, fatphobia, colorism, misogyny, and patriarchy.

To shift the conversation around equality, white people (and everyone) must address the levels of how structural oppression permeates our identities and lived experiences.

We are not broken pieces only to be dealt with in fractions, we are whole people with complicated truths. Equality can no longer be the game changer we center our work on, especially when incorporating the allyship of white people.

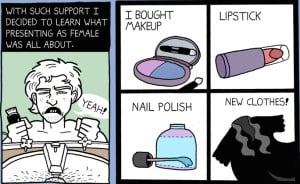

3. White Privilege

When white people name their privilege without naming the violence and oppression that their privilege is juxtaposed to, white people maintain power and hierarchy within their interpersonal and institutional navigation.

White privilege as a term only speaks to the privilege of being white, but not the power of whiteness and white supremacy. Naming privilege is now a trend and another way of depoliticizing allyship. Example: “I know I have white privilege so…”

A great example of depoliticized white allyship, aka eating ally cookies that literally mean nothing to our humanity, is Matt McGorry of Orange Is the New Black. McGorry has been a token ally in 2015 from his participation in Amber Rose’s anti-slut shaming campaign, to his selfies with Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.

McGorry’s hypervisibility of allyship is actually a reminder of how comfortable white people can be in naming their privilege but not naming their violence and power within their white privilege.

If Matt decided to donate his paycheck to Black and Indigenous People of Color out here doing this work while also trying to survive, that would be a direct challenge to white supremacist capitalism because he would use his power and access to give back to those systematically disenfranchised.

If Matt really wanted to turn up on white supremacy, he could use his power and privilege to call out the racism and anti-Blackness within media but also use his position of power to shoutout BIPOC doing this work already.

An important learning lesson for all white people in this work is that most of what you know about racism and violence has been theorized, lived, and known about long before you ever discovered it, yet alone put language to it. So it’s very important that instead of using your white privilege to name your white privilege, use your white privilege to acknowledge who suffers, dies, and remains silenced for your privilege.

This isn’t about sending you on a road of “white guilt” but rather challenging you to be uncomfortable with the truth about your position of power, safety, and convenience. Being uncomfortable is the best political place to learn and grow so we can build a world of anti-oppressive liberation.

4. Minority/Minorities

The term “minority” is not fully depoliticized but is actually a maintainer of violence and power through depoliticizing the act of naming oppressed groups. Who or what is a minority? When you really have to define who a minority is, it’s almost always a demeaning way of referring to people of color or folks who are outside of society’s defined idea of “normal.”

Minority maintains white people’s sociopolitical and cultural power by positioning them as the majority – implying that their larger demographic allows them to make decisions for everyone and violate whoever does not fit within that majority.

The term minority holds historical and systematic reminders that people of color have never been seen a fully human. There is nothing minor about us. And even demographically, we collectively outnumber the shit out of white folks.

And in reality, I feel very uncomfortable every time I hear the term minority.

Just like I never hear any white person say “White-American,” I never hear any white person call themselves a “majority.”

This is a reminder of who holds the power in language and in truth. Another reason why it makes me uncomfortable is because just like other catch-all terms for non-white people, it doesn’t actually specify who is who when we talk about specific ass experiences. For example, when we talk about #BlackLivesMatter, we’re not talking about just any “minority,” we’re talking about Black people.

Long story long, please stop using this damn term.

5. Charity

When charity is used to describe the act of “giving back” or helping the “less fortunate,” it’s important to recognize the power dynamics being upheld. White people name charity and charitable acts based upon who they acknowledge as “underprivileged.”

The underprivileged and less fortunate are usually poor Black, Indigenous, and Brown people living in lower socioeconomic areas with limited access. Charity speaks to a larger issue of how white supremacist capitalism works through the violence of anti-Blackness, anti-Indigenous, racism, capitalism, and patriarchy.

Maintaining the idea that white people are “giving back” upholds white supremacist enablement that allows for reparations to be disguised as philanthropy.

We don’t need donations when we’ve been historically stolen from. We need what’s ours.

And one the best ways (in my opinion, it is THE actual best) to utilize white privilege is through reparations.

I know, it probably sounds so unreal that money, land, and resources would be the best way to give back… but actually, it is. We are systematically and interpersonally deprived, struggling, and tired. And in order to shift power, create change, and help dismantle white supremacist violence – it requires a structural and economic shift of resources and finances.

6. People of Color

Last but not least, people of color as a term really hones in similar sentiments as “minority” but also forces us to even challenge words that seem the most politically correct. People of Color is now a more common, acceptable term to acknowledge the “minorities” and non-white people.

And although people of color is still a very political and necessary term, white people and non-white people often put us all in the same category to make it easier to acknowledge our oppression. But the issue lies within the idea that People of Color is a catch-all term.

People of Color does not actually specify components of identity and can actually conflate many forms of violence within a general scope.

For example, my experiences as a light skin Black femme is not the same as a white presenting non-Black person of color. So when white people refer to people of color as a singular group of identities and humanities, it’s important to realize how very violent that can be to our differences and experiences.

To reiterate, we are different people and deserve our own acknowledgement when addressing our truth and experiences.

***

In addressing terms such as diversity, multiculturalism, charity, and privilege – white people must name the violence that creates the need for inclusion in the first place. Without addressing the violence that makes concepts for our humanity necessary, these terms become depoliticizing ways of keeping white supremacy and current power systems in place.

Diversity is not for us or our collective liberation. If we are to grow as a community and as people in creating anti-oppressive liberation for all, cultivating new language is a necessity to creating that freedom together.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Ashleigh Shackelford is a queer, nonbinary Black fat femme writer, artist, and cultural producer. Ashleigh is a contributing writer at Wear Your Voice Magazine and For Harriet. Read more at Facebook.com/AshleighShackelford. Support my emotional and intellectual labor by donating to: PayPal.me/AshleightheLion.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more