A person sitting at a wooden table and chairs, with bookshelves lining the wall behind them. They are holding a sandwich in one hand and licking the fingers of their other hand.

I’m always thinking about how much I eat.

Seven years ago, I started tracking my calories. I also started adjusting my time around my food intake and work-out schedule – a series of complicated mathematical calculations around calories burned and consumed.

I also started structuring my thoughts and feelings around what I ate and how long I worked out.

In my mind, I had to complete at least an hour-long cardio routine for my workout “to count.” Things like having dinner with friends was emotionally, physically, and mentally draining. Or I would preemptively work out for long hours at one time to convince myself I could then eat whatever I wanted. Or I might have fun with my friends and then spent hours after dinner stewing in feelings of remorse because I “ate too much.”

On the outside, my behavior is something that is socially recognized as ideally healthy behavior. Watching what I eat and maintaining a strict workout routine – this constant surveillance of my body – is normalized as simply being health-conscious. There’s a reason they call it a fitness regime – a planned, imposed, and controlled system of fitness and diet.

The tracking and counting was disruptive to my wellbeing, yet I was convinced it was a form of self-care. My fucked-up relationship with food and working out is a disordered eating pattern, loosely defined as thoughts and behaviors that interrupts everyday habits related to food, weight, and my body.

Yes, feminists have body issues, too. As a feminist, how do I navigate my critical position as someone who resists the idea of diets and fitness as regime while also being someone who does both of those things?

While I know anti-fat societal norms privilege thin beauty ideals, I struggle in being stuck in my own desires between wanting to achieve those ideals.

I know the things I’m told about food, fitness, and my body aren’t true. I’m aware of these norms, structures, and ideals – these body myths – yet, I’m stuck in habits of both thinking and doing when it comes to my own practices of food and fitness.

I’ve internalized the idea that if I can control and manage my eating practices and fitness practices, this might magically seep into other areas of my life – like being happier or more professionally successful. I’m still waiting to love myself after I lose a few more pounds.

For me, feminism, and my process in learning and growing as a feminist, has offered me multiple frameworks to renegotiate my own practices of self-care and unpack my tense relationships around food, fitness, and my body.

Here are some of the lessons I’ve learned along the way (and am still learning).

1. Our Ideas Around Food and Bodies Are Informed by Our Intersecting Identities

Racialized and gendered expectations of body types, as well as cultural practices, influence our relationships to food, fitness, and our bodies.

Yet, race is often ignored in conversations about body image, and particularly, narratives about eating disorders and disordered eating tend to erase women of color and our experiences.

For example, Raquel Reichard has written about the curvy Latina stereotype, where media portrays Latina women with large breasts and butts, yet tiny waists and arms. Sonya Renee Taylor, who founded The Body Is Not an Apology, talks about the fetishization of Black women’s bodies as “service-object” and how Black women are less visible in body positivity and size acceptance movements.

My own negotiations of body image are tied to my experiences as an Taiwanese American woman, where there’s cultural pressure from both within and outside the East Asian American community for us to be perceived as “beautiful” and our bodies to be thin and tiny.

East Asian women are stereotyped and objectified as submissive, docile, and doll-like. We’re expected to be small and delicate – easier to dominate and control.

Being small is misunderstood as part of our imagined “racial biology.” In addition, talking bluntly about bodies and food consumption is also culturally normed; my parents and other relatives openly comment on the ways my body looks for better or for worse.

My desires to be thin are also influenced by my experiences as a queer woman in a relationship read as “straight.” There’s a feeling of erasure and anxiety about being seen as “queer enough.”

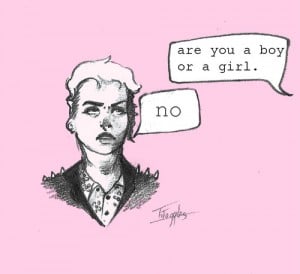

But what does it mean to “look” queer?

Is it to look like Ruby Rose? In signaling queerness, mainstream media, like fashion magazines, predominantly represent the queer body as white and thin, and often also as masculine.

There’s some part of me that believes that if I look thinner, then I’ll look more “queer.” In these ways, sometimes my curves feel like further betrayals and erasures.

Feminism has given me a way to realize my own internalization of stereotypes and cultural norms around race, gender, and sexuality and helped me push back and unpack my perceptions around my body as not being “small enough.”

2. It’s Important to Unpack Complicity in Classist and Ableist Narratives of Fitness and Food

In our current society, which prioritizes individual success and rewarding the merits of one’s work and choices, this also impacts the way we think about eating and fitness as “work” and as “choice.”

Fitness inspiration (fitspo) makes us believe that “if you don’t look like this, it’s because you’re not trying hard enough” while also assuming that financial and physical abilities are choices and also that healthy, able bodies are earned.

We end up feeling personally responsible for our individual successes or failures – and that success and failure is tied to how we look.

We’re also told in multiple ways that we need to “invest” in our health through better consumption choices, like buying organic food and nutritional supplements or spending money on workout classes.

A “good” body is tied to eating “better” food and working out “more,” but these endeavors require time, energy, ability, and money. So someone’s inability to do these two things are often dismissed as “not trying hard enough,” “not caring,” and/or “laziness” without regard to ability status and class status.

When I take up these narratives in my own beliefs and practices, I end up being complicit in in reproducing and reinforcing classist and ableist narratives about fitness and food.

For example, linking ideas of “laziness” and “hard work” in the narrow terms of how often someone is or isn’t physically moving and how “intensely” someone is or isn’t physically moving is an ableist belief that doesn’t take different individual capacities into account.

We’re judging disability, sickness, exploitation, and exhaustion as an “unwillingness” to be “healthy.”

Feminism – and largely the work of disability justice activists, food justice activists, and activists in the body acceptance movement – have helped me realize that when we’re judging ourselves, we also end up inflicting those judgments on other people.

Not only is this unpacking work important for myself and for my own body image, but important on a larger scale to undo damaging food and fitness narratives as tied to classism and ableism.

3. My Body Size Isn’t an Achievement, Nor an Indicator of My Personhood

The manipulation of my body size to be “thinner” is not an “accomplishment.” Thinness is not only conflated with healthiness, but as a marker of success.

Think about what success looks like. It’s often tied to professional success (or personal success is very much tied to heteronormative notions of romantic love, building a family, and so on). News, movies, television, stock photos, and other forms of media show us that successful people in the workplace or at home are also thin and attractive. (Cue the romantic comedy genre or weight-loss makeover shows like The Biggest Loser that are intended to “inspire” us.)

Those look good, feel good, do good campaigns tell us that our weight and body size is a stand-in for our self-worth and visual indicator of our position in society.

What underlies these narratives is that if thinness is tied to success, this also means that fatness is tied to failure.

It’s so hard to deprogram myself from these messages when anti-fat narratives are spoon fed to us through entertainment and marketing.

The narrative of fitness – particularly as it pertains to dieting, tracking, and weighing – focuses on a “lifestyle change.” These lifestyle change narratives tell us that if we change our bodies by changing our habits around food and fitness, we can change our lives.

But the history of healthcare in America is linked to the history of our body issues. Health became translated into measurements of size and weight, and ultimately then linked to other achievements. Health status also moved away from “averages” into “ideals.”

We came to believe that more ideal our body measurements are, the closer to perfect we can be.

The marketing rhetoric of commercial dieting programs like Weight Watchers and personal fitness trackers like Fitbit and Jawbone tell us that there’s a “better version” of us to discover. We can tap into these better selves if only we had some guidance on how to move and eat.

With these devices, also self-described as “slim and stylish,” we can “elevate” ourselves.

These regimes and devices create goals for our bodies, but also make us think we’re achieving other goals in our lives.

They appropriate and exploit the language of self-care, promising us that the only way to our “best” and “true” selves is through weight loss – through disciplining ourselves in our food and fitness practices.

4. My Choices Around Food and Fitness Shouldn’t Be Categorized as ‘Good’ or ‘Bad’

We’re sucked into an existential sense about our body sizes: What makes me worthwhile? What makes me in control? We link the ability to work out more or to eat certain foods (or less food), to being more motivated in other areas of life or to have more control of other areas of life.

If I can’t control my own exercise or diet, then I must be “out of control,” “undisciplined,” and “irresponsible.” Because I can choose: what I eat and if I exercise, then my failures around fitness are my own moral failures.

I make choices around eating and working out based on ways I’ve come to think about them as “good” or “bad.” This binary turns everyday sustenance and movement into a moral battle.

In assessing whether or not I want to eat a particular food, I judge it as a “good” food or a “bad” food – not based on whether or not I like eating it, but on its nutritional value and number of calories. If I end up eating a “bad” food, then I need to make up for it by “good” activity – like working out.

Eating food that’s “bad” for us is often talked about as “indulging” or “being naughty.” Working out is then atonement.

Melissa A. Fabello says, “We’re socialized into having an extremely unhealthy relationship with food and our bodies, and that in turn causes us to eat in ways that aren’t actually natural or intuitive.”

Language like “fit” and “active” inform our ideas about health and work as shaming and guilt strategies.

Categorizing these different choices around eating and working out have made me completely disconnected from what my body actually needs in terms of nourishment – physically, mentally, and emotionally.

While working out might be a way that I destress and decompress, I’ve also turned it into a moral obligation.

For example, if I feel tired after a long day and end up lying on the couch the rest of the night instead of going to the gym, I feel guilty and bad about myself, rather than understanding what I’m really doing is giving my body what it needs to rest.

In decompressing with friends over drinks, I mull over whether I really “needed” the carbs and calories of the beverages, rather than thinking about it in terms of giving my mind what it needed to destress. Or after cooking a hearty, delicious meal, rather than simply enjoying it, I end up nervously narrating my food intake.

Fitness + “healthy eating” ≠ health.

Learning more from the feminist movement has helped be begin to dismantle my current relationship to my body in order to rebuild a more loving and holistically healthy relationship.

***

I have the right to be loved unconditionally and deserve love that’s in the present.

Yet I continue to struggle to be “enough” for myself and to be worthy of my own love. What does it mean to love myself now, rather than waiting? Waiting on losing weight, waiting on changing my eating habits, or waiting on working out more.

If I approach self-care under a model of “working on the self,” I’m always in competition with my own better version.

Rather than making my health and happiness contingent on a future self, I need to re-enter into a loving relationship with my own body.

Feminism has provided me a space to begin that process on a more collective level. The feminist communities I’m part of have provided me new narratives and frameworks for thinking through relationships of food, fitness, and my body in order to recover practices of self-care in ways that don’t reinforce dominant paradigms around what it means to be whole, healthy, and happy.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Rachel Kuo is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism and a scholar and educator based in New York City. Her professional background is in designing curriculum and also communications strategy for social justice education initiatives. You can follow her on Twitter @rachelkuo.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more