A person holds up a blister pack of pills and a glass of water.

Originally published on Medium and republished here with the author’s permission.

What is or isn’t feminist when it comes to politics will likely never be fully resolved – but boy howdy, we sure do love to talk about it.

There have been acres of pixels dedicated to the debate over whether a vote for Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders was more or less feminist than a vote for the other candidate, not to mention plenty about the perceived feminism of one-time candidates like Carly Fiorina and, yes, even Sarah Palin.

And of course, there was John Kasich and his line about female voters “leaving the kitchen” to elect him – a statement which I would call arguably one of the least feminist comments uttered at a stump speech in the last decade.

Well, that is, if it weren’t for almost every single thing out of the mouths of Donald Trump and Mike Huckabee and any number of other white men who have run for or were recently elected into office.

So I completely understand the skepticism and even exhaustion around this line of political criticism and critical thinking.

But I feel quite confident in saying that, regardless of which presidential bubble you colored in on your November ballot, a vote on behalf of paid sick leave is one of the more inclusive, intersectional votes you can cast.

Basically, paid sick leave is feminist AF.

Allow me to explain.

First, let’s get it straight that intersectional feminism means raising up all kinds of people; it’s not about limiting the access or rights of men or white people or whatever else teenage trolls on Twitter seem to think.

By “feminist,” I mean paid sick leave is extremely good for furthering the cause of equity, generally. Now let’s move on.

Both an increase to the minimum wage and requiring employers to provide paid sick leave would directly benefit women and families. The majority of minimum wage workers identify as women, and minimum wage workers are the most likely to work in industries which don’t offer paid sick leave.

But it’s much deeper than that.

Before we move on, though, a note: For the rest of this piece, I’ll be using masculine and feminine pronouns for clarity. But please note that plenty of people don’t fall into one of these categories, and basically all of the data available is unfortunately based on straight couples.

I would love it if there were data on non-binary and same-gender couples, but I have been hard-pressed to find much – though, according to some of the existing research, lesbian households are pretty dang egalitarian.

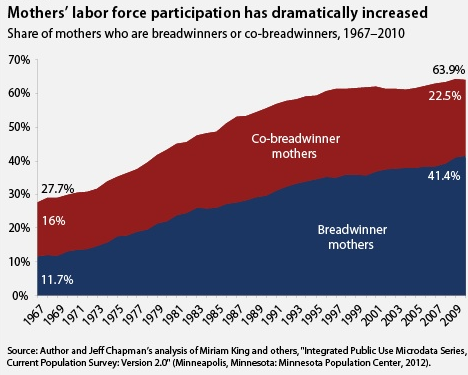

A 2009 report entitled “The New Breadwinners” found that record numbers of women are either solely supporting families, or are co-supporting their families with a partner.

In total, close to 64% of households relied on income from the mother; just over 41% were entirely reliant on her income. Which means that if she can’t take time off when she’s sick (or when someone else in the family is sick), or is forced to take a pay cut, the income of the family will certainly suffer.

This has huge implications on the gender wage gap and gender equity.

Though we often like to cite the 77 cents to the dollar figure, the truth is that the earning gap between genders isn’t just down to women being paid less per hour. It also leaves out women of color, who make way less than that – and every time a white woman cites this figure, she effectively erases that truth.

Instead, it’s important to look holistically at how women end up bearing the brunt of a lack of paid time off in their actual lives – both at work and in general.

As Melinda Gates pointed out in the Gates Foundation’s annual letter this year, “time poverty” is a real and significant issue. Unpaid work is still very much a barrier for women across the board (and across the world) because almost universally, it’s expected to be performed by women for no money, effectively limiting the amount of time they can spend on their paid work or on themselves.

Gates defines it as such:

“Unpaid work is what it says it is: It’s work, not play, and you don’t get any money for doing it. But every society needs it to function. You can think of unpaid work as falling into three main categories: cooking, cleaning, and caring for children and the elderly. Who packs your lunch? Who fishes the sweaty socks out of your gym bag? Who hassles the nursing home to make sure your grandparents are getting what they need?”

A Pew study from 2013 found an interesting time breakdown, which ended with women accounting for one more hour per week than men.

Fathers reported spending 42 hours per work on paid work, nine hours per week on housework, and seven hours per week on childcare, adding up to a total of 58 hours per week.

Women, meanwhile, reported spending 31 hours per week on average doing paid work, sixteen hours on housework, and twelve hours on childcare, totaling 59 hours.

However, in most dual-parent households, both the father and mother are working full time (and the mothers tend to disagree about how much housework the fathers actually do).

Paid sick leave, of course, can’t solely overcome centuries of conditioning, nor can it solve the problem of work created by one partner who does less of it (seriously, husbands literally make more unpaid work) .

But it can help alleviate some of the career stress and pressure that women feel as part of this work, particularly when it comes to cold and flu season. Because, of course, it’s not just the worker who needs to take time off sometimes.

A 2014 study found that in families with children, women are not only ten times more likely to stay home with kids when they’re sick, they’re also five times more likely than husbands to make and attend doctor’s appointments.

Even if the mother is working, she’s much more likely to be the one who takes time out of her day.

From the Atlantic:

“For working moms, 39% report missing work to care for their sick children, 33% report sharing the responsibility with their spouse, 16% report calling someone else to help, and 6% report their partner taking time off. Of the 39% of women who report taking time off to care for their sick children, 60% report not getting paid. That’s up significantly from 2004, when 45% reported not being paid for missing work.”

Without paid time off, women are then forced to make a choice: stay home and get docked the pay (and risk losing their job), or try to find someone to stay home with the kid, thus still losing money and also feeling terrible for not being there (not to mention potentially spreading whatever disease your child may have given you)?

The other alternative is sending kids to school sick. Though most daycares require that children who aren’t feeling well stay home, schools offer no such requirement.

Again, from the National Partnership for Women and Families:

“Parents without paid sick days are more than twice as likely to send a sick child to school or daycare as parents with paid sick days…[and] are five times as likely to report taking their child or a family member to the emergency room because they were unable to take time off work during normal work hours.”

Unnecessary ER visits, the Partnership cites, “cause additional burdens on our health care system totaling more than $1.1 billion per year.”

Even in families without children, the bulk of care-taking falls on women. In fact, caring for ailing family members, particularly aging parents, pushes women into early retirement, often because they can’t get the time off that they need.

Taking unpaid time off disproportionately impacts women because, often, they work in industries where tips are essential to their income. Three-quarters of tipped employees identify as women, according to the National Women’s Law Center.

That means that their ability to, say, pay rent or buy groceries is directly dependent on their ability to perform their job both capably and with a smile (and possibly while being sexually harassed).

That’s incredibly difficult to do when you’re sick – and it poses a huge risk to your customers. Sixty-three percent of restaurant workers admit to cooking and serving food while sick.

Paid leave is a policy that will save taxpayers money, cut down on the spread of disease, improve worker productivity, and maybe even save lives – but it will also undeniably help close the gender wage gap.

As women continue to balance the bulk of unpaid work, increasing the number of hours they do get paid for can help create a more egalitarian workforce, as well as ensure that workers at all levels are able to lead their most fruitful lives.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Hanna Brooks Olsen is a writer, small human, and a Millennial. Her interests are politics, podcasts, Pac-12 football, feminism, and Oxford commas. She is curious to a fault. Follow her on Twitter @mshannabrooks.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more