Students gathered around a globe, pointing to different places on the surface.

My senior year of college I briefly considered going to the US/Mexico border to “help women” in the maquiladoras. The program was one of many generic “Spring Break opportunities” listed on the Political Science department bulletin board at my school.

It included touring the facilities (a euphemism for sweatshops) and getting to know locals.

I thought it would be a great way to raise my level of awareness, not to mention see the working conditions with which the women in my family were familiar. Many women in my family had worked in shoe factories, not unlike the ones I would be visiting on this trip.

What I wanted to do (but ultimately never did because it felt weird) is called voluntourism. The phrase refers to “the growing phenomenon of individuals traveling to developing countries to carry out volunteer work.” Voluntourism is a response to huge economic, political, and cultural disparities in the world.

Many of us look around and see poverty and hunger in the global south and we want to do something. I get it. Hell, I almost did it.

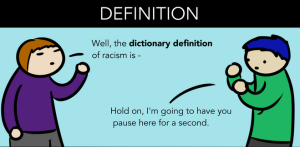

So I’m not here to stop folks from doing good work, but I do want to flesh out some of the things that make voluntourism problematic. Because while it sounds humanitarian and benevolent, recent critiques of voluntourism and gap year projects have arisen because they frequently do more harm than good.

The impetus for these programs is one of altruism and benevolence. It’s hard to imagine why going to an under-resourced country to build homes or help orphans would do more harm than good.

But it does.

Despite our best intentions, participating in voluntourism can be problematic at best, destructive at worst.

The following four points illustrate the ways ways voluntourism won’t change the world and might, in fact, deepen inequality. However, it does so with the goal of guiding you toward avenues for social justice.

1. Voluntourism Conflates Individual Gain with Justice

Voluntourism is more beneficial for the person doing it than the people they’re purportedly helping.

As JK Rowling famously said in a series of tweets, many college students pursue voluntourism because it will provide a helpful boost on their resumes or applications to graduate school.

For example, I teach at UC Berkeley where it’s not enough to just get in – students feel the pressure excel academically and beyond. Students here under-sleep and over-stress about assignments, grades, and yes, their professional futures. And because the job market in almost every field is cutthroat, graduate school has become a necessity to be competitive.

One way students can get an “edge” is through resume boosters like voluntourism and community service which show graduate student admissions and, later, corporations and organizations that you’re a well-rounded applicant.

The thing is, in all the paragraphs above, I didn’t mention marginalized third world communities once.

Embarking on voluntourism in this self-serving manner is advantageous for the person doing it, not the recipient.

While very few things in the world are totally altruistic, voluntourism creates a way for young, privileged college students to economically and culturally benefit from oppressed populations while feeling like they’re improving those communities. This kind of mindset exacerbates an already problematic relationship.

Pippa Biddle writes that the voluntourism dynamic serves to transform “the (usually western) volunteer into a benevolent giver and the community members into the ever grateful receivers of charity.” The first part of this quote is critical. Many people embark on voluntourism in order to both feel like saviors and gain a professional advantage while doing it.

But individual gain is not the same thing as social justice – and equating the two can do more harm than good.

2. Voluntourism Can Have Disastrous Effects

The United Nations is considered the peacekeeping force of the world. This year, the UN admitted to infecting the country of Haiti with cholera – a disease that hadn’t been seen in that region in nearly a century. The outbreak came from a UN Peacekeeping camp, the result of a private UN contractor dumping sewage from the camp into a main river.

The outbreak caused 8,400 of deaths. The UN denied fault for six years.

And these people are experts.

The UN was established in 1945. It’s been around for 75 years and has 193 member countries. Just to give you an idea of its scope, just one of its initiatives – the United Nations Development Program, which seeks to eradicate poverty, and reduce inequalities and exclusion – has a presence in 170 nations.

The point I’m trying to make is that even people with the best of intentions can be detrimental to a space if they’re unprepared and untrained – and most voluntourists are a combination of both.

There are people who are of huge assistance in the global south, including medical doctors, dentists, and architects – but most voluntourists are not those people. Most voluntourists do not have the skill set necessary to make real change.

Moreover, the rise in voluntourism has created an entire industry that incentivizes keeping locals out of jobs and children destitute. Imagine you want a job at Starbucks, but someone else is willing to do it for free. Then imagine that same person will actually pay Starbucks to work there. Sounds wild, right? But that’s the reality of voluntoursim programs that do things like build homes.

Finally, and maybe the worst one yet, voluntourism can actually hurt children.

Alexia Nestora runs Firefly Journeys, a large voluntourism organization. She admitted to the Guardian that big voluntourism firms love orphanage stops, “They sell the best and are the most tearjerking projects to pitch to the media. Volunteers come away with the classic picture with an orphan and tell all their friends about their experience.”

But the result is that orphanages have become businesses that rely on guilt. Ian Birrell reports, “Some are even said to be kept deliberately squalid. Westerners take pity on the children and end up creating a grotesque market that capitalizes on their concerns. This is the dark side of our desire to help the developing world.”

3. Voluntourism Assumes Neediness and Erases Blame

Curiously, voluntourism seems popular in countries where there exists a strong sense of national independence.

For instance, Haiti is the only country to have formed out of a successful slave rebellion. The people of Haiti rose up after being enslaved by the French to liberate themselves. Vietnamese folks fought off not one, but two colonial powers, and Ethiopia is Africa’s oldest independent country. It was never colonized by a European nation.

These are people who have proven their resistance to any and all kinds of foreign power, especially under the guise of benevolence because that’s exactly how colonialism was justified as a civilizing project.

Oddly and rather strikingly, voluntourism, by virtue of the dynamic it creates, says that people who live in these deeply anti-colonial places require western assistance and intervention.

Not only is this an erroneous assumption, it ignores the fact that what has really impacted these countries to the extent that voluntoursim seems like a necessity – let alone an option – is western economic policies.

Here is a short list of examples:

After the American War in Vietnam, the US imposed a nineteen-year long trade embargo that made Vietnam one of the poorest countries during that time; individuals on average made only $500 a year.

Similarly, Ishaan Tharoor for the Washington Post reports Haiti was forced to pay ten times its annual revenues in order to compensate French colonists and slaveowners for their lost profits from the slave trade.

That’s right, Haiti became a poor country because it was forced to pay reparations to the French government that enslaved it. This burden has adversely affected Haiti since its formation.

Both historically and currently, what’s detrimentally impacting these countries the most is western policies that deepen inequality both within national borders and abroad.

The North American Free Trade Agreement, established between the US, Mexico, and Canada in 1994 decreased worker bargaining power, displaced workers, and lowered wages.

Remember my opening story about visiting the maquiladoras? Those were created by NAFTA, which established a factory industry in which 60% of people working were girls as young as thirteen for a mere $55 a week.

Neoliberal policies created and implemented by the United States and United Kingdom have decreased support for the working class and increased inequality since they began in the 1970s.

And most recently, the Trans-Pacific Partnership – an ambitious secretive twelve-country trade agreement – hopes to become the next in this long line of international trade deals. But democratic senator Elizabeth Warren has said putting the TPP into effect will make it “open season on laws that make people safer but cut into corporate profits.”

Every single one of these economic policies that effectively disintegrates rights and living conditions for the working class and poor was architected by the United States. But the logic behind voluntourism erases that fact to focus – almost entirely – on the individual impact one person can have when they visit an orphanage of children displaced by the policies their country created.

4. It Stands in the Way of More Radical and Decolonizing Liberation Efforts

I just painted a bleak picture that has the potential to feel really disempowering. Most of the people reading this live in the US and have very little say when it comes to what our government decides to do abroad.

In this sense, voluntourism looks like a way one person can reshape a horribly asymmetrical world. But it buys into the same dynamic we’re trying to combat and most importantly can be downright harmful.

So what are you supposed to do as a well-intentioned undergrad? Lots, actually.

Because the effects of neoliberalism have pretty much seeped into every aspect of daily life, you can pretty much do anything when it comes to resistance.

Like advocate for different economic policies and wealth distribution right here if you want to help folks everywhere. Or, you could work against sex trafficking, one of the effects of neoliberal policies.

Organizations like MISSSEY lift up young women who have been trafficked involuntarily into sex slavery. Since I mentioned the Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership, I’ll also mention there’s an entire movement to expose and stop the agreement.

Finally, you could develop a specific skill set and cultural literacy in order to do work with a vetted organization like Doctors Without Borders. Better yet, you could be a part of trying to cultivate an economic climate so that young people in the global south have the resources they need to become doctors in their own countries.

According to Professor Johnathan Swift, approximately 25% of doctors practicing medicine in the US received their training elsewhere, mainly sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa.

Voluntourism focuses on you, the do-gooder, and your desire to help. But imagine how different the world would be if that emphasis was instead on empowering those who have been most affected by neoliberalism, poverty, and war. Isn’t that the point?

Those of us who have the privilege of even considering voluntourism have a choice.

By not doing voluntourism, we are saying that people everywhere in the world have strength, power, and self-determination. Most of all, we can put our energies toward combatting neoliberalism that adversely affects us all.

***

Voluntourism comes out of a desire to make the world a better place. There’s no doubt in my mind that every person who embarks on these trips wants to do good deeds.

Unfortunately, that benevolence is not reflected in the effects and roots of voluntourism – which is the byproduct and instigator of even more global inequality.

So instead of voluntourism, maybe try making a difference right here where inequality often begins. And trust me, it’ll feel just as good.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Kim Tran is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She’s also a collective member of Third Woman Press: Queer and Feminist of Color publishing. Her academic and activist commitments are to laborers, refugee and queer communities. She facilitates workshops on uprooting anti-black racism in Asian American communities. She is finishing her Ph.D in Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley where writes on race, gender and economics. Her work has been featured on Black Girl Dangerous, Nation of Change and the Feminist Wire. She can be found in any of these capacities at www.kimthientran.com.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more