A smiling factory worker wearing an orange vest in an industrial warehouse.

If you’re not a member of a union, you’re not alone – in the last sixty years, union membership has declined from one in three workers to one in twenty.

The decline is due to a variety of factors (including anti-union policies, trade agreements, and the decline of the manufacturing industry, among other things) and has impacted millions of workers.

But if you haven’t heard of this issue, don’t feel bad – the decrease in union membership hasn’t exactly drawn splashy headlines.

That’s because declining union membership just doesn’t seem like a big deal to most workers who aren’t unionized. White collar workers, for example, rarely need the protections that collective bargaining agreements offer them, and many service workers don’t realize that unionizing is even an option.

However, research has found that a decline in union membership actually hurts all workers. And, like a lot of issues, it disproportionately hurts folks from marginalized communities – like women, people of color, queer and trans people, disabled people, and so on.

Despite big steps in intersectionality in our collective understanding and practice of feminism, labor rights and the strength and safety of unions haven’t been championed especially loudly by feminists. Which is a shame – because the benefit and protection that unions offer workers intersect and overlap with many, many facets of social justice.

Here’s how.

1. Unions Have Been Found to Help Narrow the Wage Gap (And Not Just for White Women)

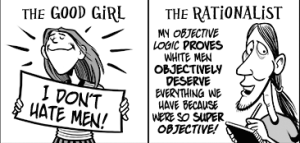

As feminists, we talk a lot about the gender wage gap – often without being fully intersectional.

When citing the (very well-documented) fact that women are, on average, paid less than men, there is also a tendency to leave out the fact that it’s not as simple as 78 cents on the dollar. Systemic racism, ableism, anti-LGBTQIA+ sentiment, transmisogyny, and other oppressive factors mean that many people across intersections are also being paid less than able-bodied white men, and that women of color are particularly vulnerable to unequal wages.

Union membership has been found to narrow both the gender and wage gaps by significant margins.

Analysis from the National Women’s Law Center found that “the wage gap among union members is half the size of the wage gap among non-union workers” and that “female union members earn over $200 per week more than women who are not represented by unions” – and that’s “an increase that represents a larger union premium than men receive.”

Additionally, despite plenty of talk about closing the gender wage gap from President Barack Obama and other top politicians, actual progress in non-unionized work has been slow. However, for union workers, the increase has been swift and noticeable.

The NWLC reports that “the wage gap among union members shrunk by 2.6 cents between 2013 and 2012 (to 9.4 cents from 12.0 cents) – for non-union workers, it was virtually unchanged (18.7 cents in 2013, down 0.5 cents from 19.2 cents in 2012).”

The racial wage gap is also slimmer in union work.

A 2016 report from the Center for Economic and Policy Research found that not only are Black workers more likely to be represented by a union than any other race, but that their wages are more likely to be competitive.

According to CEPR, “Black union workers on average earn 16.4% higher wages than similar non-union Black workers.” That corroborates earlier findings published in the American Journal of Sociology, wherein the authors referred to organized labor as an “institution vital for its economic inclusion” of Black people.

Unionization’s impact on the LGBTQIA+ wage gap remains a little murkier; while there’s some evidence that collective bargaining may help queer and trans folks achieve more equitable pay, the truth is that it’s an understudied area and one that is worth further analysis.

Unfortunately, unions can’t completely undo systemic forces which result in inequitable wages, but the ability to collectively bargain, coupled with transparency of pay scales and clear expectations of salaries, gives unionized workers a competitive edge when it comes to negotiation – and that can lead to wages which are higher, more reliable, and more equitable.

2. Union Membership Increases Access to Health Care (Which Impacts Marginalized Communities)

In the pursuit of gender equity, access to health care is a frontline defense.

Though it’s often couched as a social issue, access to reproductive care is very much a matter of economic justice. To quote the 1992 Supreme Court decision Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, “the ability of women to participate equally in the economic and social life of the Nation has been facilitated by their ability to control their reproductive lives.”

Of course, reproductive health care needs aren’t specific to women – or any one gender, for that matter. But lack of access to reproductive care definitely does impact lifetime earnings of those who need it.

Planned Parenthood cites the economic impact of access to health care – particularly on the gender wage gap. A factsheet from the provider explains the following:

“Fully one-third of the wage gains women have made since the 1960s are the result of access to oral contraceptives. And while the wage gap between men and women is still significant (particularly for women of color) and must be addressed, access to birth control has helped narrow the gap. The decrease in the gap among 25-49-year-olds between men’s and women’s annual incomes ‘would have been 10% smaller in the 1980s and 30% smaller in the 1990s’ in the absence of widespread legal birth control access.

So it’s significant, then, that union membership is a good indicator of access to health care, generally.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics found in 2013 that 79% of union workers have employer-provided medical benefits – compared to just 50% of non-union workers.

And a CEPR report found that, in the service sector, “those in unions were about 19 percentage points more likely to have employer-provided health insurance, and about 25 percentage points more likely to be in an employer-provided pension.”

Health care access isn’t just limited to reproductive rights, either.

Access to medication for chronic illness, mental health, or even just the common cold can increase a person’s earning power and productivity and impact the health of their greater community. That means that the decline in union membership has real-world effects on the health and economic security of folks of all a/genders.

Of course, access to health care in and of itself is not a solution – the healthcare industry is still harmful to trans folks, for example – but as far as feminist issues go, this is an essential one, and it’s one that unions have gone a long way to address.

3. Union Membership Increases Access to Paid Time Off

It’s a known fact that the United States lags behind the rest of the industrialized world when it comes to access to paid family leave for parents of all a/genders, but it’s not just maternity and paternity leave that workers are lacking. More than 41 million workers in the United States don’t receive a single paid sick day.

That’s unfortunate – and logistically problematic – because paid sick leave policies necessarily benefit women for numerous reasons. Chiefly, this is because women are still overwhelmingly more likely to take on caregiver roles.

Women are twice as likely to be the caregivers of their elderly parents and ten times more likely to take a day off of work to take a sick child to the doctor. When they don’t have access to paid days off, though, that can mean a lack of income or worse, lack of a job.

This is borne out in the data, as well. Though the average caregiver is employed, they are also two-and-a-half times as likely to live in poverty due in large part to missed wages or part-time work.

Union membership, on the other hand, gives women the labor protections that the federal government doesn’t require, ensuring paid time off that can be used both when a worker herself is sick, or when she is taking care of someone else. 82% of union workers have paid sick days – compared to just 62% of nonunion workers.

There’s also a strong argument that organized labor and the protections it offers workers, benefits everyone because it helps workers stay home when they’re sick.

Public health officials have long championed paid leave policies as a way to control the spread of disease throughout communities, which reduces productivity. Additionally, when parents have paid days off, they can stay home with sick kids, which helps contain contagious diseases, as well.

4. A More Inclusive, Intersectional Workforce Benefits Everyone

Possibly one of the most encouraging elements of organized labor is its emphasis on inclusion and elevation of all workers.

Whereas both the private and public sectors have talked a big game about closing gaps and reducing unemployment levels of people of color, LGBTQIA+ folks, disabled people, and many other intersections of identity, organized labor has actively pursued a more inclusive workforce that offers nondiscrimination protections.

In the introduction to And Still I Rise, a combination report and love letter to the labor movement from Black women, authors Kimberly Freeman Brown and Marc Bayard wrote that “if you are concerned about the economic advancement of black women, families, and communities, you must think twice before you dismiss the value and importance of the labor movement. No question about it, the fact that black women covered by collective bargaining agreements fare better than their counterparts without one makes unions worth fighting for.”

Meanwhile, AFL-CIO has been working to educate its members about issues that face LGBTQIA+ workers, paying special attention in the last year to the workplace discrimination that trans folks face.

“A strong union contract should protect transgender working people at every point of their transition,” they wrote in a blog post this summer. “Work with your local union leadership to ensure your contract fully includes [LGBTQIA+] workers and families in every aspect, from general workplace non-discrimination to family benefits.”

Some groups are still being left behind, though.

Latinx workers are less likely to join a union, despite working in fields which often offer collective bargaining, something Secretary of Labor Tom Perez has spoken strongly about.

As more and more workers in traditionally lower-wage jobs – like hospitality and service – join unions, they actively see increases in wages and expansion of protections and benefits, meaning they’re able to stay in the workforce longer and work their way up the ladder.

Essentially, unions offer a path forward in what are otherwise often viewed (thanks to classism and the moralization of service work) as “dead-end jobs.”

While women, broadly, have been touted many times over as “the new face of the labor movement,” it’s important to remember that workplace protections and higher wages which benefit women actually benefit everyone.

The economy is, on the whole, more robust and functional when the most people are actively participating and being compensated for their participation.

If we want a strong workforce, it must be inclusive and equitable – and organized labor has made huge strides in ensuring that’s the case.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Hanna Brooks Olsen is a writer, small human, and a Millennial. Her interests are politics, podcasts, Pac-12 football, feminism, and Oxford commas. She is curious to a fault. Follow her on Twitter @mshannabrooks.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more