A fat person stands in front of a brown background, holding a cup of coffee and looking skeptical.

I remember the first time I went to a queer people of color-centered party that I felt truly had potential.

I was hopeful that, for the first time, I would not feel left out in a queer space. I imagined that through being surrounded by other queer people of color, we would all finally be on a level playing field, and I could feel accepted, included, valued, and wanted in ways I had never felt in queer spaces that cater to white folks.

But I was so wrong – and so disappointed.

Even though there were no white folks present, it was still apparent that those who looked whitest were still the in-crowd. It was still the light-skinned ones, the thin folks, the masculine people, the ones without any visible disabilities.

As a fat person, I still felt so invisible and unwelcome, even though I was also a person of color like those around me. This felt like an even deeper betrayal, as it wasn’t white people for whom I have low expectations who were harming me – it was people with whom I was meant to be in community.

This experience really helped me see how white supremacy manifests in subtle ways in activist spaces, even by folks who identify strongly as people of color and/or as anti-racist and anti-oppressive.

I now see how even cultivating activist communities and spaces that consist of primarily young, thin, cis, and non-disabled people is a product of white supremacy, even if the people are not all white.

White supremacy isn’t about individual white people, though they are often the ones who benefit the most from it, and the ones who have the most at stake in upholding it. The intimacy of white supremacy is that whiteness as a standard becomes permeated throughout our lives in the ways we conceive of and conceptualize nearly every aspect.

This is a guerrilla tactic that allows even the most well-meaning and intentional people (both white and of color) to accidentally participate in it.

White supremacy no longer needs white people to maintain its status. This is most obvious to me in the ways non-Black people of color perpetuate anti-Blackness, which is another aspect of white supremacy.

This is how we can shift it.

1. Complicate Your Oppressions

An essential component of working through all the ways we have all inevitably internalized white supremacy is by thinking through all the subtle ways it appears in our lives – not only the ways that it is harmful, but also the ways we benefit from it, even as people of color.

For instance, people like myself benefit from light skin privilege by being in closer proximity to whiteness than darker-skinned folks, even if we still experience racism. And our oppressions do not outweigh our privileges. They live in conjunction.

It is so common for us, especially as we begin to learn about concepts of privilege and oppression, to really embrace our identities as people of color and begin to see all the very real ways that racism has impacted our lives.

Unfortunately, many of us often forget the other ways we’re privileged.

Even being able to use your eyes to read, or access technology to get on the Internet to read this without being made ill are privileges that we don’t often consider.

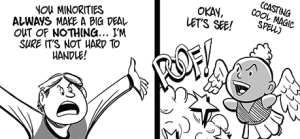

Concepts of privilege and oppression are shaped to be intentionally ambiguous. They are meant to be confusing so that they can make invisible the ways even the oppressed can oppress others.

We need to be asking not just how we are oppressed, but how we are privileged – including through thinness.

2. Remember That Thinness Can’t Be Separated From Whiteness

The way most people have been taught to think about body size is through the Body Mass Index, or BMI chart.

But what people don’t know is that the BMI was created by a Belgian statistician named Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet, who used what was available to him – all white adult European men – for his study.

And recent examinations of the BMI have shown that racialized bodies don’t measure up the same way. So in addition to all its other problems, the BMI is, quite frankly, racist and sexist.

The idea of what we have been taught to believe a “normal” body should look like is literally based on ideas of white male bodies and has become translated onto bodies of color across the world.

This isn’t to say there are no thin people of color or fat white people. But regardless of what body the fatness or thinness on, its size and shape still references (or doesn’t) a body ideal rooted in whiteness.

By recognizing the white origins of the worshiping of thinness, we can begin to think about where, exactly, our personal and cultural distaste for fatness comes from.

We can begin embracing the body diversity of ourselves and realize how, when we get down on ourselves or others for being fat, we are enacting white supremacy against ourselves and others.

And we can recognize that an inclination (of any kind) to thinness, no matter on whose body it is on, cannot be separated from an attraction to whiteness in the current context and history of race and body size.

3. Stop Using Fatness as a Stand-In For Race

Even the way that fatness becomes talked about in popular culture shows how fatness and race have become subtly correlated, even amongst people who probably consider themselves progressive, not racist, and/or otherwise body positive.

In 2013, white television starlet Lena Dunham called herself “thin for Detroit” on The Howard Stern show, demonstrating how fatness has become racialized, where “Detroit” becomes code for Blackness.

Similarly, white actress Tina Fey’s quote from her memoir, about the pressures placed on (white) women to have “full Spanish lips” and a “Jamaican dance hall ass,” has been thoroughly critiqued for its association of racial stereotypes and body size.

Both of these comments reproduce ideas that communities of color are more accepting of fatness by virtue of being stereotyped as more attracted to it.

But Black and Latinx communities are actually pathologized for higher occurrences of fatness under white ideals of thinness – statistics that can’t be disentangled from the occurrence of fatness in impoverished communities and the disproportionate number of people of color who live in poverty.

All of these realities are the produced through white supremacy and capitalism structuring our society.

4. Recognize How We Judge Ourselves Against White Standards

We uphold whiteness in a lot of subtle ways. One of the most obvious is through internalized fat hatred and conceptions of what our bodies should look like.

How are we comparing ourselves to white standards that were never meant for us? Not just with body size, but aspects like height, color or shade, and body hair patterns.

I frequently get told that I “look young,” which is a complicated statement, and typically intended as a compliment. In our culture, youth is a virtue. And I constantly see people my age or younger who “look” older, which has led to a lot of confusion and insecurity.

Eventually, I realized that many of the people I was judging myself against were white, and factors like sun damage, a fatness that smooths out skin, and genetics that determine things like bone structure and hair patterns impact what gets reduced to become physical markers of age and, implicitly, maturity.

It occurred to me, then: I looked young because I didn’t look white. That what others around me were interpreting as youth is simply a fat brownness. I don’t look young – I look like me.

This is apparent in other racialized braggings about youthful looks. Jokes about Black and Asian people aging particularly “well” are subtle comparisons of people of color to whiteness.

After all, what do they age in comparison to? Whiteness.

And while a surge of jokes about the poor longevity of whiteness has arisen in pockets of communities of color, the fact that, popularly, the way we talk about aging bodies is invisibly set against a standard of whiteness is one that is yet to be truly revealed.

How else do we liken ourselves to whiteness?

5. Stop Comparing Our Bodies, Our Health, and Our Family Structures to White People’s

We also perpetuate whiteness when we buy into diet culture and are critical of our own bodies and the bodies of those in our communities.

I’ve had so many conversations with friends of color about the way that the bodies of people in our family are “different” and, quite simply, naturally fat. Even with the indication that our bodies are “different” re-centers this ideals – one which has been established as by whiteness.

And we still continue to harbor fat stigma, even by accepting increasingly debunked medical myths about the correlation between fatness and (un)health.

But what is wrong with being unhealthy?

I would say that an aversion to unhealth also comes from whiteness. They were the ones who rounded up all the sick and segregated them in the Dark Ages. This anxiety towards sickness sounds like intergenerational trauma and stigma.

As Dr. Huhana Hickey has noted, “[T]he conceptualization of disability is steeped in Westernized concepts of impairment.”

She goes on to say that:

Disability as a Westernized concept is that it is based on a Westernized human rights and disability framework that is often considered individualistic. Indigenous peoples do not easily work as individuals or within individual constructs, however, but embrace a concept of collective or group mentality.

Folks of color have always incorporated our sick into our lives and taken care of them. We have always had more interdependent ways of living.

But the segregation of disabled folks arose with industrial societies – again, informed by whiteness through capitalism and, in the US, colonialism.

It is so important to remain critical of all our expectations and desires, where they come from, and who and what they ultimately uphold.

6. Be More Conscious of Body Diversity in Our Circles – Beyond Simply Race and Fatness

Like the party I mentioned before, so many activist and community spaces geared towards people of color continue to cater to thin bodies. We are invited into these spaces under guises of a shared struggle, but as a fat person, I often feel simultaneously hypervisible and invisible in them.

When I’m the only fat person, or one of the few, or the fattest person, it’s very obvious in contrast to those around me. Consequently, their fat hatred encourages them to ignore or interact with me minimally. It’s disheartening, especially if I am the only one who notices, or mentions it.

Similarly, it’s not uncommon for queer and people of color-centered events to take place in buildings that are not wheelchair accessible or are not scent-free, barring so many people of color with disabilities from participating.

If these accommodations are not barriers for us and we show up to these events without asking who is missing and demanding they be welcomed and accommodated, we are being complicit in erasing and forgetting members of our community because it’s convenient for us.

Whenever I see a photo of someone I know who is white in a group photo with exclusively other white people, I always wonder if they notice that there are no people of color around.

And I do the same for fat folks with thin people of color. And when there are no trans or disabled folks (that I know of). And so on.

I do this not to tokenize folks, but to wonder how aware we are of who we surround ourselves with. We have to remember that the oppression of all “non-normative” embodiments can be linked to whiteness when (thin, cis, straight, non-disabled) whiteness is the normative embodiment.

And we uphold whiteness by creating homogenous communities – by excluding not just fat, but trans, disabled, and dark-skinned people from our dating pool and friendship circles.

When we value the thin, cis, and non-disabled people in our lives romantically and platonically at the expense of those who are fat, trans, disabled, and of color, we’re replicating these white supremacist notions of humanity in very intimate ways, even if no one in the relationship is white.

It’s so easy to fall into these traps.

But if we’re honest with ourselves about who we surround ourselves with and why, and begin to unpack the internalizations that are excluding certain folks from our lives in so many ways, we can begin to live truly rich and full lives.

Chances are, the people we often leave out can enrich our lives in a multitude of ways. And, if we are lucky, we can enrich their lives, too.

***

Through being more aware of our own internalizations, their origins, and their implications, we can add another lens to fat positivity, as well as a more comprehensive understanding of how white supremacy works.

These are both lifelong and difficult journeys, but we have to be diligent.

Body diversity is racial diversity, and racial diversity is body diversity!

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Caleb Luna is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. They are working-class, fat, brown queer living, writing, performing, and dancing in Oakland, California. They are a first-year PhD student at University of California, Berkeley, and their work explores the intersections of fatness, desire, fetishism, white supremacy, and colonialism from a queer of color lens. You can find more of their writing on Black Girl Dangerous and on Facebook and Tumblr.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more