A smiling baker holds an ‘open’ sign in a bakery.

Originally published on Medium and republished here with the author’s permission.

Riddle me this: If you knew with some degree of reasonable certainty that a gradual increase of the minimum wage would not leave the economy – either locally or nationally – in worse condition than it would be otherwise, would you still object to doing it?

In a recent study released by the University of Washington, and presented to the Seattle City Council earlier in December, researchers noted that in the aftermath of the city’s landmark minimum wage increase – which will eventually raise workers to $15 over the next several years – businesses continued to open, workers’ salaries continued to rise, and unemployment continued to decrease.

Researchers concluded that while “the share of workers earning less than $11 per hour declined sharply,” and that “overall, the Seattle labor market was exceptionally strong over the 18 months from mid-2014 to the end of 2015.”

Additionally, the study found that “Seattle’s job growth rate tripled the national average between mid-2014 and late 2015.”

The same researchers found, earlier this year, that the minimum wage increase also had minimal impact on prices, and that business owners were generally successful in dealing with the new requirements.

Essentially, the city is raising the minimum wage, and it’s going fine. This is in line with other historical data, which has found that in most instances of minimum wage increases, employment has increased.

As more cities and states choose to raise their wages – and as big corporations fall in line, opting to increase their workers’ pay – we can reasonably expect to see a growing body of research which indicates that, contrary to long-standing conservative talking points, raising the minimum wage doesn’t sink the economy, and may actually offer a great deal of public good.

Which brings me back to my original question: In the presence of this data – and in the absence of figures, thus far, which indicate increases to the minimum wage result in catastrophic job loss or business closures – what rationale remains for keeping wages so low that it creates a hardship for (and all but necessitates the use of social services by) full-time workers?

Mostly, it seems that the persistent objections to raising the minimum wage are based in a moral idea of who should be paid highly, rather than grounded in data about who is paid highly, or even decently.

Of course, it’s easy to decide that “burger-flippers” deserve to live in poverty (though, of course, I’d argue that service work, including fast food restaurant work, is every bit as skilled as the much-touted factory jobs we’re all clamoring to get back), but this moralization begins to fall apart when it’s confronted with the reality of who, exactly, earns low wages – and how important their jobs really are.

Often, arguments against raising the minimum wage are couched in an idea of personal responsibility – if you want to earn more, you need to go back to school, gain more skills, and then go into a field that pays more.

“Learn more, earn more,” the saying goes.

But what about the chronic low wages of workers who we all can agree are necessary and skilled? What does the market – which is supposed to be sentient enough to set its own rates based on demand and value – say to that?

Image description: Black-and-white drawing of a person wearing a suit and pointing to text that reads, “Don’t like the minimum wage? If you’ve got minimal skills, minimal education, and provide a minimal contribution to the workplace, why the hell should someone be forced to pay you more?”

Take, for example, childcare professionals. Much like everything else around you, the cost of childcare has increased significantly over the last twenty to thirty years. However, it’s decidedly not due to an increase in the cost of labor – many childcare workers make just under $10 per hour, meaning they’d receive a pay raise if the minimum wage were increased to $10.10, $12, or $15.

As a result of these low wages, many full-time, working childcare professionals are reliant on social services like food stamps, despite additional training and certifications and the general collective idea that childcare is a really important service that certainly does not “provide a minimum contribution.”

We can all agree that America’s half-million professional, skilled childcare workers provide an essential service to our communities and our economy. Without childcare, working parents simply wouldn’t be able to work, which would greatly diminish the productivity of the workforce, while also reducing the total number of jobs.

We can also all agree that potential childcare workers should probably be incentivized to both get into and stay in the industry (by the way, high turnover and lack of stock due to low wages is a large reason why your childcare is so expensive) with wages that don’t require them to be on food stamps.

The solution, then, is simply to require that they be paid more.

But, if you take the hard line of moralized minimum wages – that because the people who watch our children paid a low wage, that must be what childcare is worth, or that if they really wanted to make more, they’d leave the field, effectively leaving your child with someone who’s less qualified – you might be thrown into a bit of a quandary.

Similarly, many professions that we think of as extremely important and at least somewhat skilled – the kinds that we think of as “good jobs” – are simply paid too little, due in large part to the extremely low floor of the minimum wage.

Home health care workers, for example, earn just $10.70 an hour, though one in four reportedly earn less than the minimum wage. Meanwhile, paramedics are lucky if they clear $15 per hour – while the lowest 25th percentile can expect to earn $12 or less.

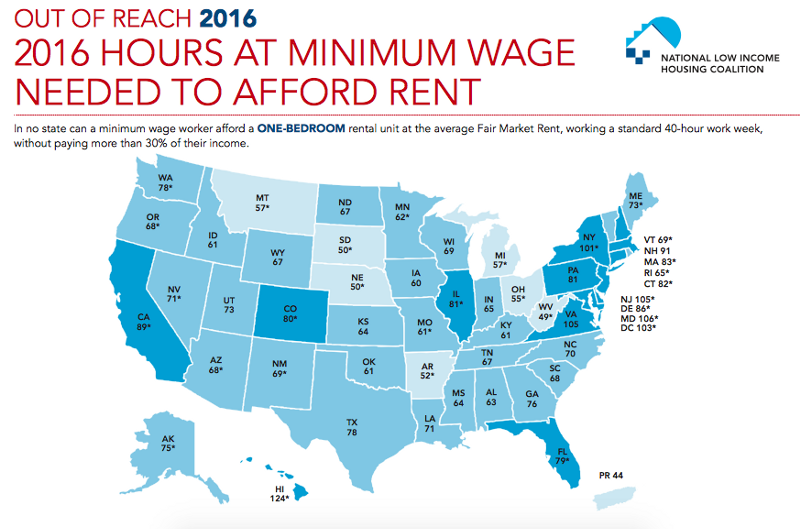

In most states, that’s barely enough to rent a one-bedroom apartment, let alone support a family.

A map of the US, with the states color-coded to illustrate the number of hours at minimum wage one had to work in 2016 to afford rent for a one-bedroom apartment.

Again, then, the answer is: Pay them more. Pay childcare workers more, pay paramedics more, pay home health care workers and nurses and teachers and lifeguards and farm workers and customer service professionals more.

At what point do we stop picking out which jobs we think deserve more and decide, collectively, that no one who works full time should live in poverty, whether we decide that their contribution is “minimal” or not?

Because I’d argue it’s right around the time that the data shows that doing so – that raising the minimum wage – doesn’t reduce the economy to ruin and, instead, has many, many benefits.

There’s substantial evidence indicating that raising the minimum wage to $12, $13.50, or $15 would increase the salaries of both retail workers, restaurant employees, and other laborers who we frequently think of as the typical minimum wage worker as well as those in more morally prized professions, like health care workers.

Therefore, raising the minimum wage is good for everyone.

If, using the existing data and ignoring the classist rhetoric around who “deserves” to make a living wage, it is reasonably clear that a modest, gradual minimum wage could turn the tide on income inequality and increasing poverty in the US, but you still find yourself objecting to it, ask yourself why.

Is it because you genuinely don’t believe that it would be good for the economy, data be damned, or is it because you genuinely don’t believe that everyone’s time is worth at least enough money to get by?

Thanks to Paul Constant.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Hanna Brooks Olsen is Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a writer, small human, and a Millennial. Her interests are politics, podcasts, Pac-12 football, feminism, and Oxford commas. She is curious to a fault. Follow her on Twitter @mshannabrooks. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32