When you’re a sex and relationships writer, the “what do you do?” conversation can get really personal really fast.

Mostly, people are intrigued. But there is the occasional uncomfortable chuckle or joke along the lines of “I’d better be careful around you” or “now I’m scared,” especially if I mention that I’m a feminist writer.

At family gatherings, I usually drop “sex” and just mention the “relationships” part. But I’d like to get up the confidence to tell my great aunts and uncles that I write about masturbation and porn. Why shouldn’t I?

These topics are treated as unfit for polite conversation, but I’ve never quite understood why. They’re not necessarily physically disgusting. They’re not morally wrong. They’re not inherently offensive.

But when people find out I write about them, they often either treat it as shameful or congratulate me for not being ashamed, which also implies that my career is shameful.

Or they operate based on the stereotype that women who are open about sex must be super kinky or into hookups. Sometimes, they even take it as an invitation to say sexual things that actually do cross the line.

Here are some of the things people say when they find out I’m a sex writer – and the problematic social norms they reflect.

1. ‘You’re Really Brave’

Often, I get comments like: “Thank you for having the courage to write about sex,” and “Was it scary for you to put all that out there?”

When people say this, they’re trying to compliment me.

But here’s the thing: In order to be brave, you have to overcome fear. So, by telling me I’m brave, you’re telling me I’m scared. Why would I be scared to talk about something as common and harmless as sexual desire?

And asking me if I’m embarrassed because people know I had an eating disorder or have insecure thoughts during sex implies that this information is embarrassing. Again, why should I be embarrassed?

Granted, some people do feel embarrassed about these things – and that’s okay – but they shouldn’t be expected to. And by assuming they are, we’re encouraging the idea that they should be.

If we don’t want people to be ashamed of themselves, let’s stop assuming they are. And let’s stop “helping” them hide things they shouldn’t have to hide.

Don’t offer people sweatshirts to cover up period leaks when they may not mind others seeing their menstrual blood. Don’t ask if they’d like to go somewhere private for a discussion about sex if they seem comfortable having it in public.

And don’t call us brave for doing something that isn’t and shouldn’t be scary.

2. ‘You Seem Like a Sexual Person’

Upon learning I wrote an article about how to have great sex, one male friend responded, “So you’re down with hookups?”

And when I said sex and relationships were among the topics I covered, a man I just met told me, “Are you a very sexual person?”

I still don’t know what that means. I think “very sexual person” is just the label women get for having sexual desires other than the desire to be desired.

And as my friend’s “So you’re down with hookups?” comment suggests, what “sexual” usually means in this context is sexy – sexual in a way that caters to the male gaze. Or, in Paris Hilton’s words, “sexy, but not sexual.”

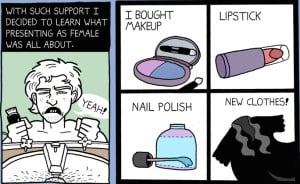

The stereotype is that any woman who is interested in sex is a seductive vixen who loves to please men (because she’s also assumed to be straight). The stereotypical sex writer wears red lipstick and miniskirts and is an expert on blowjobs.

That’s because it’s very hard for people to picture a woman with a sexuality that’s not a performance for men – who is sexual, but not sexy.

In other words, it’s hard to picture me. I’ve recently gotten off a plane and haven’t showered in two days. I don’t shave my legs, and I’m sitting at a table bent over my computer with a puffy jacket and frizzy hair.

That’s what a sexual person looks like, because my sexuality isn’t about what I look like. It’s more about what I look at.

A woman who looks without waiting to be looked at is considered inconceivable. A woman who writes about sex without first being written into a man’s story is considered rebellious.

So, when a woman looks or writes, we assume she likes being looked at and “written” about – that is, defined by men. We assume it’s rare for a woman to even be interested in sex.

Writing about sex does indicate an interest in the subject matter, but it doesn’t mean you actually want to have sex more than your average person. Besides, it’s totally normal for women to be interested in sex, whether their work involves it or not.

3. ‘What Do Your Parents Think of That?’

I’m a grown-ass woman. Why would I base any work-related decisions on my parents? And why would my parents feel weird about me talking about sex?

I know why people think they’d have an issue. They probably believe that it’s just creepy to think of your kids as sexual. But it doesn’t have to be if you’re sex-positive and unashamed.

They also probably believe it’s hard for my father to know his daughter is “corrupted.” Women are supposedly impure once they’ve had sex, and it’s considered their fathers’ jobs to protect their purity.

Actually, I don’t think it’s hard for him at all. My dad is more worried about things that would actually harm me, like being dumped or losing my job, not enjoying healthy sexual relationships.

Actually, I don’t think he worries about any of that stuff. Because, once again, I’m a grown-ass woman. My parents aren’t particularly worried about me at all.

Yet random people who learn what I do are very concerned about my folks’ mental health.

The reality is, I’m not letting them down by being a sex writer because there’s nothing upsetting about my profession. And I don’t have an obligation to do what pleases them anyway.

4. ‘So Do You Write About, Like, Fashion and Beauty?’

To be fair, this comment isn’t unique to conversations about being a sex writer. It comes up whenever I mention writing about women’s issues or writing for women’s interest publications.

The underlying assumption, of course, is that certain topics are “women’s” topics, and they’re all kind of the same, so if you’re interested in one, you must be interested in all the others.

This is insulting because it encourages a stereotype that certain things are of interest to women and others are of interest to men, that non-binary people don’t exist at all, and it ignores the possibility that women could be interested in more serious things.

When I say I write about women’s issues, people assume I mean weight loss and makeup, rather than workplace sexism and reproductive rights.

When I say I write about sex and relationships, people assume I mean seduction methods and sex positions, rather than consent and empowerment.

This paints a one-dimensional picture of what women care about – and depicts us as stereotypes, rather than individuals.

***

I sincerely doubt I’ll ever live in a world where you can say “I’m a sex writer” in front of most people and they’ll treat it the same way they would if you said “health writer” or “politics writer.” But I can challenge people to envision one.

When someone reassures me that they won’t tell anyone about what I do (yes, someone really once said that to me), I can ask them what would happen if people knew. When someone makes a joke about what my dad must think, I can tell them he’s probably glad I’m helping spread information that many people need.

When people tell me I’m a very sexual person, I can reassure them that in fact many women are very sexual, so I’m not unique in that regard.

And when people assume I teach women how to be sexy, I can explain that actually, I’m more concerned with empowering them to be unabashedly sexual.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Suzannah Weiss is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a New York-based writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Salon, Seventeen, Buzzfeed, The Huffington Post, Bustle, and more. She holds degrees in Gender and Sexuality Studies, Modern Culture and Media, and Cognitive Neuroscience from Brown University. You can follow her on Twitter @suzannahweiss. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more

Most Read Articles

- « Previous

- 1

- …

- 30

- 31

- 32