Co-authored with Soraya Chemaly

As weeks stretch into months and beyond, how many conversations are sounding something like this?

What more can I do?

How does anything I can do make a difference in the world?

I’m overwhelmed.

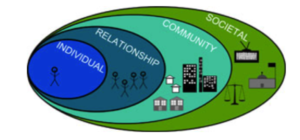

There is a picture that clears a view. It’s called the social ecological model for change, and it can help anyone organize their intent, time, and actions.

It looks like this:

While the model captures the intersectional and inclusive nature of social change – each of us overlapping and intersecting through space and place – it also invites us to see a new view, shifting emphasis from What can I do to make change? to Where can I make a change?

When we picture ourselves in particular spaces, places we can see – our own homes, workplaces, schools, towns, and city halls – we may feel a little less adrift.

It’s a simple visualization (and just one of many models used to represent the dynamics of social change) of a systemic response to the more complex questions: How, exactly, can I fight racism, misogyny, anti-semitism, anti-immigration, anti-queer- and trans-antagonism, ableism, fat-shaming? How do we prevent more harm?

Or, in a positive frame, how do we promote more health, safety and, simply put, more humanity, less hate, in the world?

All four spaces – societal, community, relationship, and individual – must be engaged to create and sustain long-term social change, the thinking goes. This doesn’t mean that, as individuals, we have to act in every one of those areas, but, rather, that we can act in many different ways and places.

It also means that we’re part of a larger, more powerful whole – one inclusive of individuals and political parties, which, of course, are comprised of individuals, making a tidy, if obvious, case in point for the model’s logic.

The model was developed as a public-health tool over decades – for anti-violence in particular – and is based on accumulated research and scholarship in such diverse fields as public health, sociology, biology, education, and psychology. It provides a simple organizing frame around what can easily feel chaotic and overwhelming.

Ideally, multiple levels of the model are engaged at once, with a wide range of people working collaboratively, rather than through top-down interventions, across a wide range of activities.

Each of us has different stories, different views and definitions of the four spaces. This means each of us has different ideas about how we participate.

Social movement historians will tell you that social movements rely on multiple, overlapping actors, working across a broad spectrum of engagement, from politicians to school board members, NGO directors to PTA volunteers, protest organizers to protest marchers.

Activism has to infuse every level of society and virtually every institution that humans participate in, from families to schools to places of worship to legislatures and courtrooms and city streets.

The model reinforces that the personal is political, that individual beliefs aren’t confined to the individual who holds them. This is important, because sometimes we get the message that we don’t, as individuals, have much power.

Grassroots movements are a vital response to moral shock. They are catalysts.

In an interview with Onnesha Roychoudhuri at Rolling Stone, L.A. Kauffman, author of Direct Action: Protest and the Reinvention of American Radicalism, says, “While you need a complex mix of ingredients to make change, direct action is like the seasoning that can change the alchemy of the whole situation through people’s boldness and willingness.”

Yet, three days after more than four million people took to the streets for the Women’s March, New York Times columnist David Brooks declared, “Marching is a seductive substitute for action in an anti-political era.” What we need, he wrote, is “a better nationalism.” “A central vision.” On this front, he said, “the march didn’t come close.”

However, the Women’s March was the largest, most diverse and organic display of a “better nationalism” that this country has seen in decades.

At last week’s March for Science, which reportedly grew from a single online comment, tens of thousands in 600 locations on six continents turned out to champion science “as a pillar of human freedom and prosperity.”

Both endings and beginnings, grassroots movements like these are acts in themselves: messy, complex, versatile, and, right now, historic in scale. This moment’s resistance has a long tail, and this is a long game. Generations long.

Maybe Brooks underestimated the March’s reach because, well, women, trans people, non-binary folk, and other marginalized people represented in the movement still aren’t definitively central to his, or most people’s, conception of patriotism, revolutionary fervor, or national identity.

While organizers – all of us – need to keep moving forward until we fully recognize and include each other, especially those who are still experiencing and speaking up about their exclusion, the unprecedented millions who marched put on global display an emerging vision for human rights, dignity, and justice.

The March’s participants rejected the election’s resurgent heterosexual white male Christian supremacy. And this matters.

Brooks voiced the opinion, shared by many that, “Sometimes social change happens through grassroots movements, but most of the time change happens through political parties.”

Political parties have, in the past, been powerful forces for change. However, they have done little over the history of this country to propel women, particularly the most marginal, into political life and leadership. Political parties are, in the words of the National Democratic Institute’s Sandra Peppera, spectacular “gate-keepers of the gender status quo.”

Today, we have an openly and actively hostile cabinet that is the most white and most male in a quarter century.

The grassroots is vital to change. Political parties and the media, both steeped in system justification of the status quo, are hardly tools available to the coalition brought together by the March. It has taken a century of disparate social justice movements to reach the point where focusing on this central animating obstacle to equality is possible.

Suggesting the power of political parties, serious business, is somehow diminished by grassroots organizing, “a seductive substitute,” is more than an oversimplification and a sure indicator of privilege if ever there was one. Labeling grassroots organizing “a seductive substitute,” using a term, it’s worth noting, commonly used to describe sexual attractiveness – is also, some say, false.

Consider the influence of millions of individuals who inundated Congress with phone calls, packed Town Hall meetings, and rallied in public spaces to defeat the Republican plan to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Consider that Emily’s List has seen a 1,000% increase in women interested in running for office – some 12,000 women – since Trump was elected.

We march forward, alone and together

Linda Hirshman, attorney and author of Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution and Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World, emphasizes that social movements are socially complex. It’s all hands on deck.

Some will shape central visions for a better nation. Some will serve in Congress. Some will march. Some will call. Some will donate. Some will run for office. Some will organize. Some will teach. Some will write.

Each one of us matters. In 2011, a study conducted across 57 countries found that individual acts of sexism lead to gender inequity in a society.

“You could get the impression that having sexist beliefs, or prejudiced beliefs more generally, is just an individual thing – ‘my beliefs don’t impact you,’” said the lead researcher, Mark Brandt of DePaul University.

But this isn’t true. If people are prejudiced in their homes and relationships, that society becomes less equal, too.

This means that investigating the stuff we’re made of can be a force for large-scale social change – by listening to those who don’t share our views, asking questions, reading widely, stepping outside historically etched borders of identity, challenging our beliefs, maybe by marching for women for the first time.

Imagine the concentric circles around each of the four million-plus people who marched. If even fifty percent of those folks had four conversations – at a PTA, church, diner, bar, or office – that’s eight million more people engaged.

So, What Can We Do Differently? How Do I Make A Difference?

Below is a starter kit of ideas from researchers, educators, and everyday activists like you. This isn’t intended to be a comprehensive list or prescription.

There are as many ways to take action as there are people in the world. What actions might you envision in any or all of these spaces?

1. Individual

What are your attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in relation to gender, race, sexual identity, immigration? What’s your personal history? How do you define yourself?

Can you change to support equity, respect, and nonviolence? How?

- Be introspective. Ask questions.

- Talk less, listen more.

- Consider your sense of humor and the tolerances it might reflect.

- Review the media you consume and set out to read, listen to, and watch more diverse stories and perspectives.

- Think about how your assumptions about race and gender shape your own identity and relationships. Are they full of stereotypes?

- Pace yourself at a speed that keeps you from crashing. How fast can you go, how much can you do, while remaining functional, healthy, and loving? Remember that there’s a rich and full spectrum of capacity. Some folks have the steel to work in an ER. Others don’t. But everyone can help exactly where they are.

2. Relationship

With whom do you live? Whom do you love? Whom do you take care of? Who takes care of you? Partners, family members, peers?

How do you influence their behavior and contribute to their experiences? How do they influence you? How might these relationships change, or change you?

- Have the hard conversations. Talk openly and honestly with children, spouses, family members about topics that, to this point, have often been categorized as unpleasant, “too political, not for polite company,” or just plain unacknowledged in any way.

- Be a good bystander, rejecting or intervening when you see or hear behaviors that support violence or discrimination.

- How are chores and responsibilities distributed in your home and among your family members? Does everyone do domestic work? Does everywhere share in leisure time? Are lines drawn in strictly gender-based ways? If you pay children an allowance for chores, do they get paid equally for their work?

- Say thank you to the people around you, and acknowledge their contributions to your life.

3. Community

Where do you work, go to school? What neighborhood do you live in? Are there meetings you can attend that influence processes or policies? Boards?

What could you organize to reach neighbors and friends?

- Reach out to neighbors you may not have spoken to or spent time with before.

- Consider the ways in which you might cultivate a sense of community and fun with the people around you.

- Find out which local, grassroots organizations are doing work that you support and donate time and money.

- In person, meetings, gatherings, challenge your institutions – churches, schools, libraries – to take firm stands on issues of social justice.

- Launch a social media campaign on campus, in your school, or church, create a workgroup that proposes a bill in that community.

- Start a book club or monthly dinner around key ideas and themes

- Find out how your school and after-school programs approach social justice conversations with students.

- Join your school board or PTA.

- If you’re a school volunteer, consider how traditional volunteering planning and opportunities exclude working and single parents.

- If your place of worship doesn’t allow girls and women to participate in ministerial roles and public leadership consider ways that might change.

4. Societal

Are you registered to vote? Do you have access to policy-makers? Are you a policy-maker yourself, with influence over social norms, policies, and laws that support or undermine equal rights?

Are you part of a political party, nonprofit, or company that influences health, economic, educational, or social policies that reinforce or maintain economic or social inequalities between groups in society?

- Through program creation – a social media campaign, a conference, a workshop, a community group – target lawmakers to increase support for policies that support equal rights.

- Press or support elected officials with phone calls, letter, petitions, and donations.

- Run for office.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Catherine Buni is a writer and editor whose work has been backed by The Investigative Fund and published by the New York Times, theAtlantic.com, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Verge, among others.

Soraya Chemaly is a media critic, writer and activist whose work focuses on free speech and the role of gender in culture. Her work appears regularly in Salon, the Guardian, the Huffington Post, CNN.com, Ms., and other outlets, and she is a frequent media commentator on related topics.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more