How’d your April go this year?

As an autistic person, I dread every April. Most commonly known as Autism Awareness Month, but reclaimed by the autistic community as Autism Acceptance Month, the month is aimed at supporting the autistic community.

But depending on how that support is executed, it can be fairly problematic and can actually hurt those of us in the autistic community.

I – and many other actually autistic advocates – don’t think we really need any more autism “awareness.” A majority of people in the United States are aware of autism.

What we really need is autism acceptance, and we need allistic (non-autistic) allies to participate in this.

The autistic community has been asking for acceptance since we’ve existed, but now that most people have a general idea of what autism is and how it might affect someone, we want our allies and advocates to go a step further: Show up for us, and support us in the autism acceptance movement.

Here are some ways to make it happen.

1. Ask Autistic People What We Need – And Then Listen to Us

One of the most glaring issues with a lot of (often well-intended) autism awareness campaigns is that they fail to ask autistic people what we actually want and need.

For example, many autistic people don’t want a cure. What we want is the world to be accessible to us, and people to be accepting of our differences.

I don’t want a cure for my autism. Instead, I want non-autistic and neurotypical people to understand that I have trouble with too much sensory input, and to offer to turn on captions when we’re watching TV if I’m having a hard time keeping up with the dialogue.

The best thing you can do if you want to support the autism acceptance movement: Ask autistic people what we want or need, and then listen to and respect what we say.

If we don’t want you to talk about a cure, or refer to autism as an “epidemic,” please listen to us.

If someone you know would prefer to be called autistic, rather than a person with autism, respect that choice to self-identify. If an autistic person tells you that stimming helps them self-regulate during conversations, allow them to do so.

Accepting autism means accepting autistic people, and meeting us where we are.

2. Make Your Events and Plans More Accessible to Us

Accessibility means more than just wheelchair ramps and braille signage. For autistic people, it might mean things like making sure the venue doesn’t have loud or flashing lights, or that there’s a quiet place to rest.

Since accessibility isn’t a one-size-fits-all situation, your best bet is to either speak to the autistic people you’re inviting, or if you’re planning a bigger community-wide event, to get input from a variety of autistic and disabled people about their needs.

When you don’t make any effort to ensure an event or plan is accessible, it sends the message that either you don’t really care if autistic people come, or that if we do come, you want us to find a way to either accommodate ourselves or “suck it up.”

The burden of making sure events are accessible often falls to disabled people, and it’s really helpful if you make the first move as an allistic person to see what we might need.

If my friends and I are choosing a restaurant for dinner, one of our considerations is accessibility. Beyond wheelchair and other mobility accessibility – which we care about because several of us use mobility aids and have physical disabilities – one of our most common questions is, “How loud is this restaurant?”

Because a few of us are autistic or have similar sensory issues, it can be really hard for us to hold conversations in a restaurant that’s loud, especially if there’s a live band playing or the restaurant doubles as a bar or nightclub.

It’s important to us that the restaurant we choose is as autism-friendly as possible, although food establishments generally tend to be hard on folks with sensory difficulties.

Helping out with this is as simple as starting the conversation when you’re making plans or setting up an event. Bring it up with autistic people, and ask us what would make the event accessible for us to attend.

Taking the first step in showing that accessibility is a priority to you shows us that you not only want us to be there, but that you want us to be as comfortable and safe as possible.

3. Don’t Support Autism Speaks and Other Hate Groups

Many autistic people have pointed out that Autism Speaks is repeatedly problematic.

Between the very low amount of money (4%) they spend on autism support services, and the fact that they regularly advocate for a cure over autism acceptance, a lot of autistic people really dislike and fear the organization.

I really dislike Autism Speaks because they use fear tactics to get people to think of autism as an epidemic that requires fixing. I think of my autism as somewhere between a learning disability (not every autistic person feels this way) and natural neuroatypicality.

What’s even worse is that Autism Speaks is essentially the face of the autism awareness movement, and one of the non-profits people automatically think of when they think about autism.

If you want to support autistic people, don’t support Autism Speaks. Instead, support:

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network

- Autistic Women’s Network

- National Council on Independent Living

- Rooted in Rights

4. Prioritize and Center Autistic Voices

It’s fantastic that you want to get the word out about your support.

As an autistic person, I really appreciate the accountable allies and advocates who I know are speaking up – spreading the news that Autism Speaks isn’t a great group, telling folks that we don’t need to cure autism, and breaking down myths and stereotypes.

If you want to be a great ally, you should also center and prioritize actually autistic voices.

When you’re sharing on a topic, if possible, offer links to work by autistic activists who’ve been showing up for the autism acceptance movement.

Share your favorite autistic bloggers, vloggers, and artists. Share an essay or article by an autistic person about the subject you’re educating others about.

Whenever you’re trying to be a positive ally to a marginalized community you’re not a part of, it’s important to recognize the amount of privilege you have as an outsider, and use that privilege to amplify the voices of the people who are being oppressed.

When you’re talking about why autism acceptance is so much better than autism awareness, center our voices. Use your platform to share what we have to say.

5. Challenge Your Internalized Ableism

Sometimes, I’ll come across people who are working hard at being accountable allies, but they’re still dealing with internalized ableism.

They might say something like, “I want you to come with us, but I don’t understand why driving in large cities is so hard for you. Can’t you just deal with it? We all hate traffic.”

Comments like these minimize the very real sensory challenge that I have when I’m driving in large cities, like Boston, Providence, or New York – which is exactly why I avoid driving in large cities with concentrated populations and a lot of walking traffic.

When I’m dealing with sensory overload, it’s not just an inconvenience that I wish I could avoid. It literally stops my brain from processing information correctly, or at all, making it dangerous or impossible to continue driving.

If you’re going to show up for autistic people, and you’re outside the community, you need to challenge your internalized ableism on a regular basis. And yes, you can still have ableist thoughts and behaviors even if you’re also disabled or neuroatypical – and it’s still important to challenge that ableism.

Ask yourself: “Am I respecting what this person is telling me and giving them the benefit of the doubt? Am I making assumptions here, based on my own abilities? Is there any way that I can step back from my initial reaction and challenge any myths or stereotypes I may have believed?”

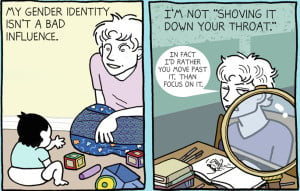

Society unconsciously sends the message that autistic people (all marginalized people, really) need to try to conform to the norms as much as possible, to not take up space, to not be loud or needy.

Keep this in mind when you’re reacting to questions about accessibility, discussions about accommodations, or any other casual conversation with autistic people.

We face very real and dangerous ableism that tells us that we shouldn’t exist, and it’s helpful if our allies can be accountable and remind us that they respect us for who we are.

***

As much as I can talk about autism acceptance and why it’s so important, it really helps me to have supportive, accountable allies who are advocating for the same thing.

Because, as an autistic person, I’m at a disadvantage when it comes to publicly speaking up about autism-related issues – even though you’d think I’d be regarded as an expert because of my experience.

The truth is most autistic people are brushed away and passed off when the conversation turns to autism – and the megaphone is usually handed to our loved ones and our medical professionals. We need to have a voice and a say in the autism acceptance movement, and in how we’re treated with respect and dignity.

That’s where allies come in.

An accountable ally is a part of the movement because they really believe in it, and wants to meet autistic people where we are, and use their privilege as a platform, rather than shouting over us and taking control of the conversation.

An accountable ally wants to amplify our voices and make them heard by a larger audience. An accountable ally wants to make sure spaces are accessible to autistic people. They work to respect and center our needs and wants.

An accountable ally is constantly challenging ableism – both other people’s and their own – because they know we’re all part of a system of oppression.

During the month of April and beyond, I see my accountable allies. And they mean more to me than they could ever know, simply because they do the hard work of showing up for me when most of the world wants me to make myself invisible.

[do_widget id=’text-101′]

Alaina Leary is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Bostonian currently studying for her MA in publishing at Emerson College. She’s a disabled, queer activist and is on the social media team at We Need Diverse Books. She can often be found re-reading her favorite books and covering everything in glitter. You can find her at her website or on Instagram and Twitter @alainaskeys. Read her articles here.

Search our 3000+ articles!

Read our articles about:

Our online racial justice training

Used by hundreds of universities, non-profits, and businesses.

Click to learn more